9.0 Central Administration

- 9.1 What Is Included?

- 9.2 Why Address Agency GHG Emissions?

- 9.3 Level of Effort

- 9.4 Complementarity/Consistency with Other Transportation Goals

- 9.5 Who—Roles and Responsibilities

- 9.6 Inventory Development

- 9.7 Goal and Target Setting

- 9.8 Strategy Identification

- 9.9 Strategy Evaluation

- 9.10 Implementation

- 9.11 Monitoring, Evaluation, and Reporting

- 9.12 Self-Assessment: Central Administration

9.1 What Is Included?

This section includes greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from the buildings, supplies, and travel associated with department of transportation (DOT) office functions. It does not include maintenance yards, heavy-duty fleets, construction operations, highway lighting, or other DOT facilities that serve the operation or maintenance of the system; these are covered in the sections on operations and maintenance.

Examples of GHG considerations in this section include

- Electricity procurement.

- Space heating fuel.

- Energy efficiency of installed appliances [heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) and lighting].

- Energy efficiency of movable appliances and electronics.

- Employee travel for work related purposes, in light-duty cars and trucks.

- Employee commuting.[1]

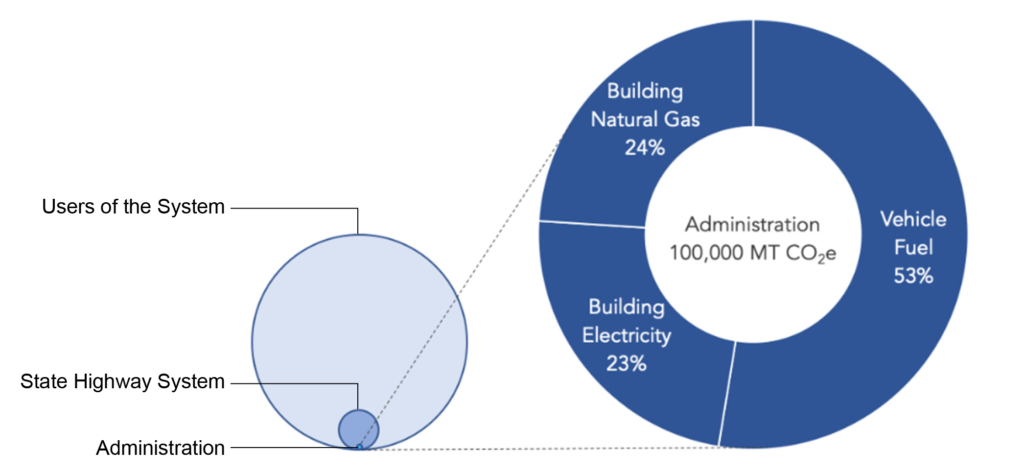

- Onsite renewable energy generation.

As shown in Figure 9.1, for a typical State DOT, about half of emissions from the listed sources are from the agency’s light-duty vehicle fleet, with the remaining half split between natural gas (heating and water heating) and electricity for heating, cooling, lighting, and appliances.

Figure 9.1 Administration GHG Sources

Source: Estimates by Good Company using data from Florida, Minnesota, Oregon, Texas, and Washington State DOT sustainability and GHG inventory reports.

9.2 Why Address Agency GHG Emissions?

While the scale of the emissions from a DOT’s buildings and light-duty fleets is small compared to the transportation system and the users of the system (about 0.2 percent), the DOT maintains a high level of influence over emissions from its facilities and vehicles, and the actions taken tend to be highly visible and symbolically important in conveying agency GHG commitment to both employees and external stakeholders. It is technically possible, if not always fiscally practicable, to reduce nearly every emission to zero or near zero (including through the purchase of offsets, as well as emission reduction measures) with very few disruptive changes. (See Section 2.9 for a discussion of offsets.)

9.3 Level of Effort

This area of management already exists and perhaps is the easiest to make happen inside of the regular cycles of procurement. Many DOTs own or rent and manage their office spaces and their light-duty fleet, while other States rely on their general services agency to provide these functions. Either way, the path to reducing emissions is the same, just with different parties involved.

Calculating the DOT’s GHG footprint from facilities and fleets is relatively easy since it can largely be done based on utility and fuel bills. Some effort is required to develop and evaluate energy and emission reduction strategies. There will also be up-front fiscal impacts from procuring and installing energy-efficient materials and converting to lower-carbon fuels, but these may result in long-term cost savings. The State energy agency and/or local utility may offer programs that can assist organizations in inventorying facilities and selecting appropriate efficiency technologies.

While energy efficiency and clean energy technologies continue to evolve and improve, there is no pressure to buy an appliance before it is ready. Some agencies establish a procurement policy for facilities and fleet that directs a prioritized hierarchy of criteria for selecting appliances, vehicles, and energy forms. This is most helpful in a distributed building and fleet management system. However, in a more consolidated or centralized facilities and fleet program, the policy may not be needed. What is needed is a careful understanding of the agency’s buildings and fleet requirements and a thorough review of technologies at the time of any upgrade or purchase. Proactive consideration of replacement options can help to ensure that efficient technologies are considered in the event of a systems failure requiring an emergency purchase.

Current Practice in DOT Energy Efficiency and GHG Reduction

Interviews with staff from 14 State DOTs and a review of agency documents conducted in the fall of 2018 found the following activities:

- Data tracking—A number of States are tracking building energy (electricity and fuels for heat), fuel consumption for vehicles, water consumption, and waste materials disposal. A few States also have development standards based on “Green Building” principles that improve efficiency beyond building codes [such as Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) or Green Globes].

- Electricity procurement—Very few agencies procure renewable electricity (sometimes called green power), but many States have mandates moving the future electrical supply in their State towards all renewable power at the agency level or for the entire state.

- Gas procurement and offsets—No State DOTs mentioned that they were buying carbon offset gas or carbon offsets to net out the GHG impacts of building and water heat.

- Energy efficiency of installed appliances—Energy efficiency of lighting and thermal loads for space conditioning and cooling are standard operating procedure for many States. Some agencies have engaged with energy service companies (ESCOs) to assess their buildings for cost-effective changeouts that will yield enough savings to pay for the installations up front. Depending on State-level procurement rules, ESCOs are either allowed or statutorily banned due to their finance method, which involves debt financing.

- Passenger fleets—A number of State DOTs reported that they have purchased some electric vehicles (EVs) and some hybrid vehicles.

- Rooftop solar—Some States have installed solar on their facility rooftops as an additional means to substitute renewable for non-renewable energy.

9.4 Complementarity/Consistency with Other Transportation Goals

GHG reduction strategies considered in the DOT’s offices and passenger fleet can also support other goals, including

- Staff comfort inside buildings.

- Reduced onsite pollution from gas appliances and/or diesel equipment.

- Longer battery life in portable electronics from energy-efficient displays and processing.

- Advancement of the market for electricity towards renewables and low-carbon power.

- Advancement of the market for EVs through volume procurement, allowing employees to drive them to get familiar with the technology, and demonstrating that the technology works when on the road.

- Reduced vehicle tailpipe emissions of other pollutants.

- Messaging to the public and employees of agency GHG intent.

9.5 Who—Roles and Responsibilities

Implementation roles within the DOT may include

- Executives—Often a Governor has established an executive order relating to facilities, energy efficiency, green power, and EVs. In the absence of a statewide order, agency management may still mandate better energy performance, green power, natural gas offsets, the use of EVs, and incentives to reduce the carbon intensity of employee travel.

- Facilities Director—The facilities director should determine when and how energy and emission reduction measures are prudent. It is essential to take a life-cycle view of these decisions as most of them come with savings over time and may be a better value, even if the technology is more expensive up front. For the procurement of renewable power and offset gas, the rules of the State, utilities, and State utilities regulators should be consulted to see about a direct power purchase that does not rely on the grid mix provided to all retail customers. At the scale at which a DOT consumes power, an energy procurement of renewable power may be cost competitive or less expensive than traditional retail paths, especially with added charging load from EVs. In most DOTs, the billing for power is decentralized and tied to unique meters, which are added one by one over time. If aggregating all bills to determine an annual consumption number is difficult with DOT records, utilities can be requested to roll up all bills they deliver to the DOT for a total number. Note that in billing, the DOT may have many terms for the same thing, e.g., “highway department, highway division, DOT, Department of Transportation, Maintenance District #4.”

- Light-Duty Fleet Administrator—Fleets are often tightly managed according to the life-cycles of the vehicles, their total costs, and their warranties. Fleet administrators should look at the total investment of charging stations, reduction in maintenance activities, and reduction in fuel cost and vehicle first price, along with the usual concerns regarding capacity, utility, and off-road capability. For vehicles that need to be taken beyond the range of currently available EVs, especially in mountainous or very hot or very cold weather, vehicle selection may consider a plug-in hybrid vehicle instead of an all-electric EV.

Roles outside the DOT may include

- General Services State Agencies—In some States, the management of office buildings and light-duty fleets and the procurement of appliances and electronics is performed by this agency on behalf of the DOT.

- State Energy Offices—Depending on the State’s context, State energy offices can often play a supporting role. Many support the assessment of facilities (energy audits), the procurement of building energy, the use of ESCOs to provide services such as energy supply and conservation, and the distribution of financial assistance (grants or loans) for clean energy technologies.

9.6 Inventory Development

For a simple GHG inventory, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA’s) Center for Corporate Climate Leadership has published a Simplified GHG Emissions Calculator. This tool allows for calculating GHGs from building energy use and fleets. This tool is adequate for Central Administration but not for functional areas related to the planning, development, or maintenance of the highway system or the users of the system.

For the carbon footprint of buildings, gather all utility bills for the year and multiply the units of electricity and natural gas by the emissions factors for electricity and natural gas. If the DOT is relying on the retail electricity mix, contact the utility to get that emissions factor. If information cannot be obtained from the utility, regional average emissions factors may be found in the U.S. EPA’s eGrid.[2]

For the carbon footprint of vehicles, multiply the total number of gallons of fuel consumed per year by appropriate emission factors. The U.S. EPA regularly updates a document titled “Emission Factors for Greenhouse Gas Inventories” that provides emission factors for fuels for multiple pollutants. The U.S. Energy Information Administration also publishes carbon dioxide (CO2) emission factors for fuels, in a webpage and spreadsheet entitled “Carbon Dioxide Emissions Coefficients by Fuel.” If life-cycle emissions are being inventoried rather than just direct emissions, life-cycle emissions factors can be estimated using the Argonne National Laboratory Greenhouse Gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy Use in Transportation (GREET) model or carbon intensity values provided by California Air Resources Board (CARB) (2020).

9.7 Goal and Target Setting

Goals or targets can be set for reducing emissions from an agency’s buildings and fleets. Targets can specify a percent reduction by a given year or year(s). The most aggressive target, which is potentially feasible for the scale of emissions from a DOT’s operations, would be a “net zero” target in which emissions are reduced as much as possible and the remainder is mitigated through offsets.

Goal setting can be paced with the regular turnover of an agency’s program. For buildings, consider engaging an ESCO or State energy agency for a comprehensive energy assessment to determine the cost-effectiveness of an early upgrade. The assessment should make it clear where it is worth accelerating equipment turnover. If maintenance and budget are an issue, a savings-based financing package may be possible.[3]

Fleet vehicles can be replaced as fast as the agency’s program procures vehicles. The cost of installing electric charging stations needs to be considered. While quick charging is rarely needed for local use (a trickle charge overnight will be sufficient most of the time), the added electrical service to the fleet parking lot is a logistical and cost issue that must be studied carefully.

9.8 Strategy Identification

GHG reduction strategies for buildings and fleets include

- “Green” or renewable energy electricity procurement.

- Procurement of natural gas offsets.

- Procurement of more energy-efficient building systems and installed appliances, including HVAC, water heating, and lighting.

- Procurement of more energy-efficient movable appliances and electronics.

- Procurement of more energy-efficient or alternative fuel light-duty vehicle fleets.

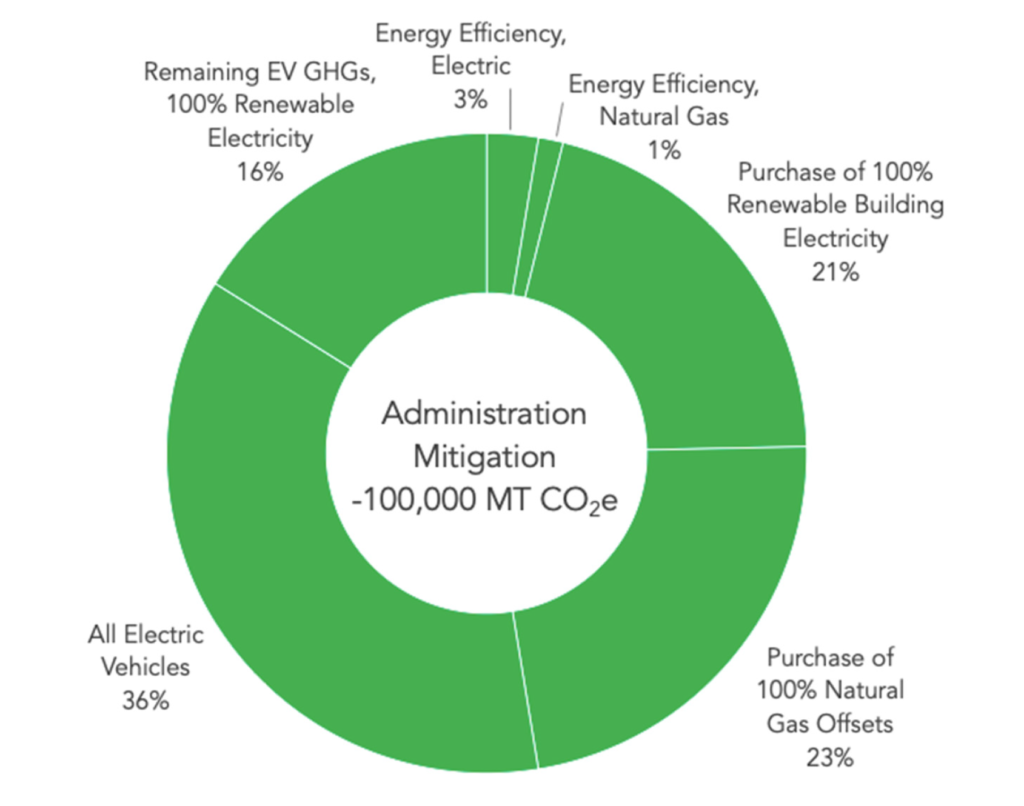

Figure 9.2 shows an assessment of how 100 percent of GHG emissions from a sample State DOT could be mitigated through reductions or offsets.

Figure 9.2 Central Administration Mitigation Strategies and Potential

Source: Estimates by Good Company using data from Florida, Minnesota, Oregon, Texas, and Washington State DOT sustainability and GHG inventory reports.

In addition to reducing emissions directly generated by its buildings and fleets, the DOT may take steps to reduce indirect emissions associated with its operation, such as encouraging employees to commute by carpool, vanpool, transit, or nonmotorized modes; implementing policies to support telecommuting or compressed work weeks; and providing telecommunications equipment to facilitate “virtual” meetings.

9.9 Strategy Evaluation

All of the options described in the following are best considered from a total cost of ownership or life-cycle perspective. Rather than comparing first costs and ignoring the cost to operate, determine the life of the device or commodity price over time. Essentially, this task is best done by finding the lowest cost strategy for the same effect. This benefit/cost assessment will show the least expensive items to be done first, as well as identifying higher cost strategies that might have large benefits and warrant strategic investment.

Electricity procurement—Nearly every utility in the country has voluntary green power available for purchase at a modest price increase. Large consumers of power may be able to negotiate a power sourcing contract through the utility that reduces the cost of supply significantly over traditional retail rates. These energy products most commonly rely on solar or wind, while others may be biomass or biogas based. Note that “renewable” and “low-carbon” may not be equivalent. While hydropower is considered very low-carbon energy, it is not deemed “renewable” due to its ecosystem impacts on water flow and fish. Nuclear power is also a low GHG power source but similarly is not considered “renewable” due to its potential risks. The State energy office can provide further guidance.

Natural gas procurement and offsets—Many large market gas companies provide voluntary programs for built-in offsets for the equivalent amount of gas used onsite. These programs are nearly identical to green power programs in that once a customer has signed up, there is nothing else to do but pay the bill.

Energy-efficient HVAC and water heating—Heat pumps are common in moderate climates and can provide both heat and cooling in an economical way. The technology is rapidly advancing, and newer models are coming to market that expand the range for cooling and heating on hotter or colder days. These show promise of performing in areas where the range of temperatures goes beyond moderate. The heat pump technology also is migrating to water heating. Gas and electric heat pump water heaters that are substantially more efficient than traditional hot water heaters are now on the market.

Energy-efficient lighting (for buildings and highway lighting) is undergoing a rapid shift to light-emitting diodes (LEDs), which generally consume substantially less energy than older technologies and result in substantial life-cycle cost savings (Table 9.1). Determining when to replace or upgrade lighting requires a study of life-cycle costs of the current system to optimize replacement time. If it already is time to change, the color of the light should be considered. This can be a sensitive topic with staff. Fortunately, there is a wide array of color values to choose from. One side advantage to LED bulbs is that they last longer than traditional bulbs and can reduce storage and replacement costs.

Table 9.1 Comparison of Light Bulb Energy Use, Costs, and Lifetime

| Comparisons Between Traditional Incandescent, Halogen Incandescent, Compact Fluorescent Light (CFL), and LEDs |

||||||

| 60W Traditional Incandescent | 43W Energy-Saving Incandescent |

15W CFL | 12W LED | |||

| 60W Traditional | 43W Halogen | 60W Traditional | 43W Halogen | |||

| Energy $ Saved (%) | – | ~25% | ~75% | ~65% | ~75%–80% | ~72% |

| Annual Energy Cost1 | $4.80 | $3.50 | $1.20 | $1.00 | $0.96 | $0.70 |

Energy efficiency of movable appliances and electronics—For any small appliance, look for the Energy Star certification.[4] For electronics such as computers, see the Electronic Product Environmental Assessment Tool (EPEAT) certifications to determine the energy consumption of the device.[5] Also, when procuring a large number of devices at once, calculate the life-cycle cost of the devices to ensure the best value.

Light-duty vehicle fleets—When researching and comparing vehicles for fleet use, first and foremost, match the vehicle to the duty cycle. The Argonne National Lab’s Alternative Fuel Life-Cycle Environmental and Economic Transportation (AFLEET) tool can be used to assist with assessments for vehicle fleets. This tool can calculate the total cost of ownership (life-cycle cost), simple payback, and the carbon footprint of the total fleet and can assist in selecting fuels for the agency’s vehicle fleet with information on emissions and cost-effectiveness of the choices.

9.10 Implementation

Electricity procurement—Depending on the State’s laws, a State agency must either buy power from one licensed utility for each facility or choose among many parties. Regardless of the type of utility laws, the major accounts manager can discuss interest in procuring renewable power. If an all-renewable option is not offered by the local utility (or utilities), renewable energy certificates (RECs) can be purchased. These contracts are often negotiated prices, and it pays to get bids or call around to find the best provider. The companies that sell RECs are often national brokers and are therefore best found via the Internet. Also, check with the Governor’s office or air quality agency on policies for State agencies purchasing RECs or offsets.

Natural gas procurement and offsets—Some gas utilities offer their equivalent of “green power” by bundling the sale of natural gas with carbon credits (offsets) that are equivalent to the GHG emissions of burning the gas. If the local gas utility does not have such a program, the same companies that broker RECs also broker offsets in bulk, and they can be procured separately. Shop the numbers and choose the lowest-priced option (usually landfill gas capture and flaring).

Whole building energy efficiency—One way to assess and possibly finance and upgrade installed appliances is to consult the State energy agency or use an ESCO if allowed in the State. ESCOs generally require payment for the assessment services and, if they find enough savings, may be able to refund the assessment with the delivery of the efficiency program. ESCOs finance and manage the project and provide quality control of the upgrades. The State DOT may be able to finance the upgrades with borrowed money over time from the energy savings for a term that matches the costs.[6] Depending on arrangements, when the term of the contract is over, the DOT may own all the equipment and the savings then accrue to the DOT. If the savings are large enough, some ESCOs may install EV charging, solar hot water, or solar electric systems to also decrease electrical loads. ESCOs may also provide water efficiency upgrades with a similar model.

Energy efficiency of movable appliances and electronics—These should be bought as they fail or as they are needed for replacement. In some circumstances, it may be worth replacing the appliance earlier than the end of life. This typically is the case for old, high-energy-consuming devices, such as refrigerators, where replacement appliances are much more energy efficient and can provide a quick payback.

Light-duty vehicle fleets—Fleet turnover is something that is constant and, depending on fleet life span, may be an annual event. With the increasing ranges of EVs, most daily trips can be accommodated by an EV. Keep in mind that the early retrofits of parking areas to bring charging stations to them can be enough to slow down the deployment of EVs. For the first generation of EVs, ensure set-up for overnight charging areas and buy a batch of them at once. Plug-in hybrids are available when trip lengths exceed the range of EVs. Expect most of the charging to occur when the vehicles are back in the yard and are charging at night.

9.11 Monitoring, Evaluation, and Reporting

Electricity procurement—Once the deal is done for zero-carbon power (“renewable” or “green”), it is a simple matter of reporting the previous emissions and comparing them to the now zero-emission power. The onset of the contract is a good time for a press release to show the progress that has been made.

Natural gas procurement and offsets—Similar to electricity, the emissions tracking mostly involves comparing the now zero-emission heat to the baseline and sharing the good news.

Whole building energy efficiency—Energy efficiency is often difficult to normalize by occupancy or by square footage but can be recorded accurately as reduced electrical or heating load. By using actual numbers, the before and after can be calculated and shared. Updates to equipment should be considered at least every 15 to 20 years for major appliances, as the technologies rapidly improve.

Energy efficiency of movable appliances and electronics—Emission reductions are best calculated as a before and after from the equipment specifications (e.g., power rating multiplied by electricity emission factors) or as part of the overall reduction in energy demand.

Light-duty vehicle fleets—While all results can be converted into GHG metrics, a simple reporting of emissions in fractions or percentages of the fleet by gasoline, electric, and hybrid should demonstrate progress.

9.12 Self-Assessment: Central Administration

A self-assessment worksheet is provided to assist State DOT staff in determining where their agency falls on the GHG engagement spectrum with respect to their own operations (buildings and light-duty fleets) and what additional actions their division or unit may wish to take to measure and reduce GHG emissions from buildings and light-duty fleets.

Click to download – Self-Assessment: 9.0 Central Administration

[1] Not included in GHG scale graphics presented here but included in some operational GHG inventories.

[3] In some States, budgeting and/or contracting strictures on contract durations or competitive bidding arrangements can complicate or even preclude outside financing of energy (emission) savings initiatives. In such cases, assistance from the Governor’s office may be helpful in securing regulatory relief.

[4] https://www.energystar.gov/products?s=mega.

[6] Again, in some States, budgeting and/or contracting strictures on contract durations or competitive bidding arrangements can complicate or even preclude outside financing of energy (emission) savings initiatives. In such cases, assistance from the Governor’s office may (or may not) be helpful in securing regulatory relief.