RESOURCES FOR LEADING RUC IN YOUR STATE

As the lead road usage charge (RUC) agency, you are the main driver for your state’s RUC exploration. Explore this page to view key resources for lead RUC agencies, and take the three part self-assessment to get tailored recommendations for studying, implementing, or expanding RUC in your state.

SELF-ASSESSMENT PART 1: RUC Stage

Please choose the answers that best describe your state’s current environment. When you finish, you will be directed to a page where you can explore your RUC stage.

Is there existing legislation authorizing a RUC program?

Do you have an operational RUC program?

Are you looking to expand an existing RUC program?

SELF-ASSESSMENT PART 2: RUC Considerations

The considerations and associated RUC building blocks in this section may apply based on how you answer the following self-assessment questions. Answer each question to learn about factors that may affect your state’s RUC journey.

With the push to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve air quality, many states have adopted clean energy and climate change policies. States’ approaches to meeting clean energy and climate change goals may include promoting sales of EVs through rebates or tax credits or more aggressive tactics like restricting the sale of gas-powered vehicles after a certain date. Additionally, some auto manufacturers have pledged to convert their fleets to all-electric. These initiatives can directly impact transportation funding and create a more imminent need for an alternative revenue mechanism like RUC.

As of May 2022, 20 states have passed or were considering passing EV adoption goals, bans on gas-powered vehicles, or both. All of these states have set EV adoption targets over the next 10 to 20 years. Washington and California have the most aggressive policies, with Washington restricting all new light-duty vehicle sales to EVs by 2030, and California restricting such sales to zero-emissions vehicles by 2035.

Clean energy policies and increased EV ownership are great for the environment and public health, but they significantly impact highway funding that relies on fuel taxes. These policies hasten the need for states to address the resulting revenue impacts. As states move towards reaching their EV adoption goals and ban the sale of gasoline or diesel vehicles, they will need to consider how they transition away from the fuel tax as the primary source of roadway funding and move towards alternative sources of transportation revenue. The more aggressive the clean energy policy, the more urgent it will be for the state to address the issue.

The RUC implementation strategy for these states could range from a voluntary RUC program in lieu of paying any special registration fees that may be in place for EVs to a mandate for all EVs to pay a RUC. However, charging a RUC on EVs could create a public acceptance issue as it could be perceived to be contrary to EV adoption goals. This is less of a concern in states where a special EV registration fee is already in place and a RUC is being introduced as an alternative to the fee. Low-mileage EV drivers find a RUC to be more equitable than a flat fee.

Check out the following building blocks to learn more:

Even if your state does not have EV adoption goals or clean energy policies, there are other factors that may impact the fuel efficiency of your state’s vehicle fleet—and that, therefore, may impact the need for an alternative to the fuel tax.

For example, the federal government has imposed stricter fuel efficiency standards on gas-powered vehicles by establishing corporate average fuel economy standards, requiring passenger vehicles to have an industry-wide fleet average of 49 miles per gallon (MPG) in 2026. At the same time, some auto manufacturers have pledged to convert their fleets to all-electric. These initiatives can directly impact transportation funding and create a more imminent need for an alternative revenue mechanism like RUC.

Developing and analyzing economic forecasts can be important for determining the impact of greater fuel efficiency in your state, as well as how a RUC can account for these trends.

Check out the following building block to learn more:

Highway funding policy varies from state to state. Each state has a varying degree of reliance on the fuel tax for roadway funding, as well as varying reliance on complementary road funding concepts such as tolling, heavy vehicle charging, or vehicle-based fees like EV surcharges. States also vary in the ways they use other sources, such as sales taxes or general fund transfers, for roadway funding. Thus, a state’s current transportation funding portfolio informs how the state might move forward with RUC and which strategies could be most effective for implementation.

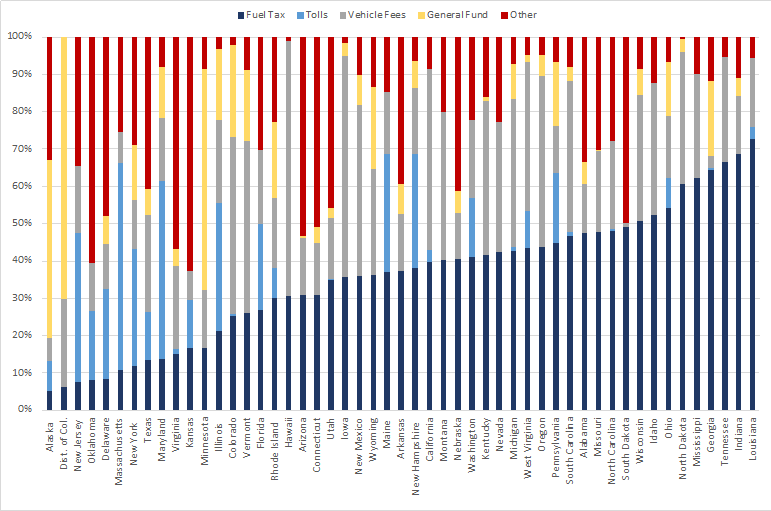

States rely on a similar mix of funding sources for their highway funding. As of May 2022, the largest sources—aside from federal funding and borrowing—included fuel taxes (32% on average), vehicle registration fees (25%), and tolls (13%). The remaining 30% came from a wide variety of sources, such as dedicated sales taxes, general fund transfers, and rental car taxes.

The following figure illustrates the breakdown of revenue sources as of May 2022 (excluding federal funds and bonding): fuel taxes, tolls, vehicle fees, general fund transfers, and “other.” The “other” category encompasses a wide range of sources, such as sales taxes, rental car taxes, and sources specific to one or a few states, like oil and gas severance taxes in Texas. As fuel tax revenues have declined, some states have begun shifting more of their funding to vehicle fees and other sources. Conduct additional research to verify that these numbers are still valid as you begin the data-gathering process.

Thirty states impose special registration fees for plug-in EVs. Almost half of these states also impose a fee for plug-in hybrid vehicles. The fees are typically assessed to compensate for EV drivers not paying gas taxes. Fees for conventional (non-electric) hybrid vehicles range from $20 to $100.

In some states, heavy vehicles are subject to weight-distance taxes or truck-only tolling. The taxes and the heavy vehicles subject to them vary by state. As of May 2022, four states collected weight-distance taxes, including Kentucky, Oregon, New Mexico, and New York. In 2021, Connecticut enacted a weight-mile tax that is scheduled to begin in 2023.

Weight-distance taxes are assessed on a per-mile basis, with the rate varying by vehicle weight and number of axles. The tax is intended to compensate for additional wear and tear on roadways by heavier vehicles. States’ rates and subject vehicle definitions differ. In Oregon and New Mexico, vehicles over 26,000 pounds must report and pay weight-mile taxes; whereas in New York, vehicles over 18,000 pounds are subject; and only those over 59,999 pounds are subject in Kentucky. Oregon’s weight-mile tax is the most mature program and collects the greatest amount of revenue. Notably, trucks paying the weight-mile tax in Oregon do not pay taxes on diesel fuel. Rhode Island has implemented a truck-only toll on all major highways and bridges.

As the vehicle fleet shifts to more fuel-efficient vehicles and EVs, states will experience different levels of impact on their current funding depending on their portfolio of revenue sources. States that rely more heavily on fuel taxes for highway funding will have a more urgent need to shift to other revenue sources than states that rely more on vehicle-based charges like registration fees or tolls. A RUC is the only alternative that preserves the usage-based component to transportation funding. States with weight-mileage taxes and special registration fees for certain vehicles like EVs may be able to leverage these programs in their transition to a RUC. For example, vehicles could opt to pay a RUC in lieu of the special registration fees.

Check out the following building block to learn more:

Some states charge a weight-mileage fee or EV-specific registration fees to supplement fuel tax revenue.

Usually levied on commercial vehicles, weight-mileage fee is a per-mile rate that is based on the vehicle’s weight. As of 2022, 4 states collected weight-mileage fees.

As of 2022, 30 states imposed special registration fees for plug-in EVs. Almost half of these states also impose a fee for plug-in hybrid vehicles. The fees are typically assessed to compensate for EVs not paying gas tax.

If your state does not utilize weight-mileage or EV-specific registration fees, it may rely more heavily on fuel taxes for highway funding. In that case, your state may have a more urgent need to shift to other revenue sources than states that rely more on vehicle-based charges like weight-mileage or registration fees.Public education and acceptance are critical components to the success of any RUC program. If a state recently increased its fuel tax or passed a major revenue package, the public may be more aware of the funding issues facing the state as a result of education efforts to get those measures passed. This can either help or hurt the success of introducing a RUC. Members of the public may believe that recently passed major revenue packages or gas tax increases will have solved funding problems, and may therefore question the need for a new funding option like a RUC. On the other hand, if members of the public and legislature understand why the fuel tax is not sustainable, they can better understand that increasing it is only a short-term solution. Recent attention to transportation funding could also impact political will to support other funding mechanisms. The messaging about RUC to the public, stakeholders, and policymakers will look different for states that have had recent success with fuel tax increases or major revenue packages compared to those that have not.

Between 2015 and 2022, 25 states plus Washington, D.C., have increased their fuel tax, and 11 states currently index their fuel tax to inflation. Sixteen states have not increased their fuel tax in over a decade. In addition, 26 states and Washington, D.C., have passed major funding packages since 2015, most of which included a fuel tax increase. Six of these packages would generate more than 1 billion dollars annually, five would generate between 400 and 900 million dollars annually, and six would generate between 100 and 400 million dollars annually.

If your state has recently completed public education and/or public opinion research about transportation, this information can be leveraged to develop a successful messaging strategy around RUC. A successful RUC policy proposal must be backed by compelling reasons to show that it is needed. This means providing evidence that supports the need for new policy and proof that the solution will resolve the problem.

Check out the following building block to learn more:

Research across the United States has shown that people generally don’t know how transportation is funded, how much they currently pay for transportation, or why the current funding model is not sustainable. As a result, the public does not perceive a transportation funding problem, making it challenging to discuss new funding mechanisms. Helping the public understand the inability of the fuel tax to keep up with road maintenance needs and how a RUC could provide a more sustainable transportation revenue stream can improve the public’s willingness to learn more about the concept.

Check out the following building blocks to learn more:

The amount of time a state has spent exploring RUC, and the level at which it has done so, plays an important role in RUC implementation options and strategies. Completing a pilot can allow a state to develop institutional knowledge about RUC and be poised to move forward in an informed manner when the timing is right. Evaluating these pilots is key to identifying lessons learned that should be considered when moving a RUC program forward.

Check out the following building block to learn more:

The exploration of RUC as an alternative transportation funding mechanism has been underway in the United States since the early 2000s.

As of May 2022, Oregon, Utah, and Virginia were the only states to have legislatively enacted voluntary RUC programs where eligible vehicle owners can opt-in to the RUC program and pay a RUC in lieu of paying special registration fees and/or fuel taxes. Connecticut has enacted a RUC for heavy vehicles. Ten states have conducted or are conducting pilots, and five states are currently in the research stage. Several states are learning from those around them through their memberships in multi-state consortiums like RUC America (a consortium of 19 state DOTs working together to share best practices, ideas, and information on RUC) and the Eastern Transportation Coalition (a partnership of 18 states and Washington, D.C., focused on the future of transportation). Only 12 states have not started or have had minimal activity in exploring this alternative revenue mechanism. As RUC is dynamically evolving in many states, explore within your agency to determine the specific history of RUC study and legislation and use this resource to explore the next steps that will help you move transportation funding forward.

The amount of time a state has spent exploring RUC and the level at which they have done so plays an important role in RUC implementation options and strategies. Moving ahead too quickly in RUC planning and implementation, especially without public and political involvement, can result in a lack of public acceptance or political support, which is ultimately what is needed to implement a RUC. Memberships in multi-state consortiums that share research and key lessons learned on RUC can provide great benefit to states, particularly those who did not budget for their own in-depth research or pilots/demonstrations. Learning insights from other coalition members that are more advanced in RUC exploration, and participating in studies and pilots with them, can allow a state to develop institutional knowledge about RUC and be poised to move forward in an informed manner when the timing is right. In any phase of RUC exploration, and especially when developing the implementation strategy, it is critical that policymakers, state executive and transportation leadership, and the public are educated and informed about RUC.

Check out the following building Blocks to learn more:

Several states are learning from those around them through their memberships in multi-state consortiums like RUC America (a consortium of 19 state DOTs working together to share best practices, ideas, and information on RUC) and the Eastern Transportation Coalition (a partnership of 18 states and Washington, D.C. focused on the future of transportation). As of 2022, 12 states have not started or have had minimal activity in exploring this alternative revenue mechanism.

The amount of time a state has spent exploring RUC and at what level plays an important role in the RUC implementation options and strategies. Moving ahead too quickly in RUC planning and implementation, especially without public and political involvement, can result in a lack of public acceptance or political support, which is ultimately what is needed to implement RUC. Memberships in multi-state consortiums that share research and key lessons learned on RUC can provide great benefit to states, particularly those who did not budget for their own in-depth research or pilots/demonstrations. Learning insights from other coalition members that are more advanced in RUC exploration, and participating in studies and pilots with them, can allow a state to develop institutional knowledge about RUC and be poised to move forward in an informed manner when the timing is right. In any phase of RUC exploration, and especially when developing the implementation strategy, it is critical that policymakers, state executive and transportation leadership, and the public are educated and informed on RUC.

Check out the following building block to learn more:

Some states are learning from those around them through their memberships in multi-state consortiums like RUC America (a consortium of 19 state DOTs working together to share best practices, ideas, and information on RUC) and the Eastern Transportation Coalition (a partnership of 18 states and Washington, D.C. focused on the future of transportation). As of 2022, 12 states have not started or have had minimal activity in exploring this alternative revenue mechanism.

If your state is not a member of a multi-state RUC consortium, your state may rely more heavily on intrastate research and pilots.

Check out the following building blocks to learn more:

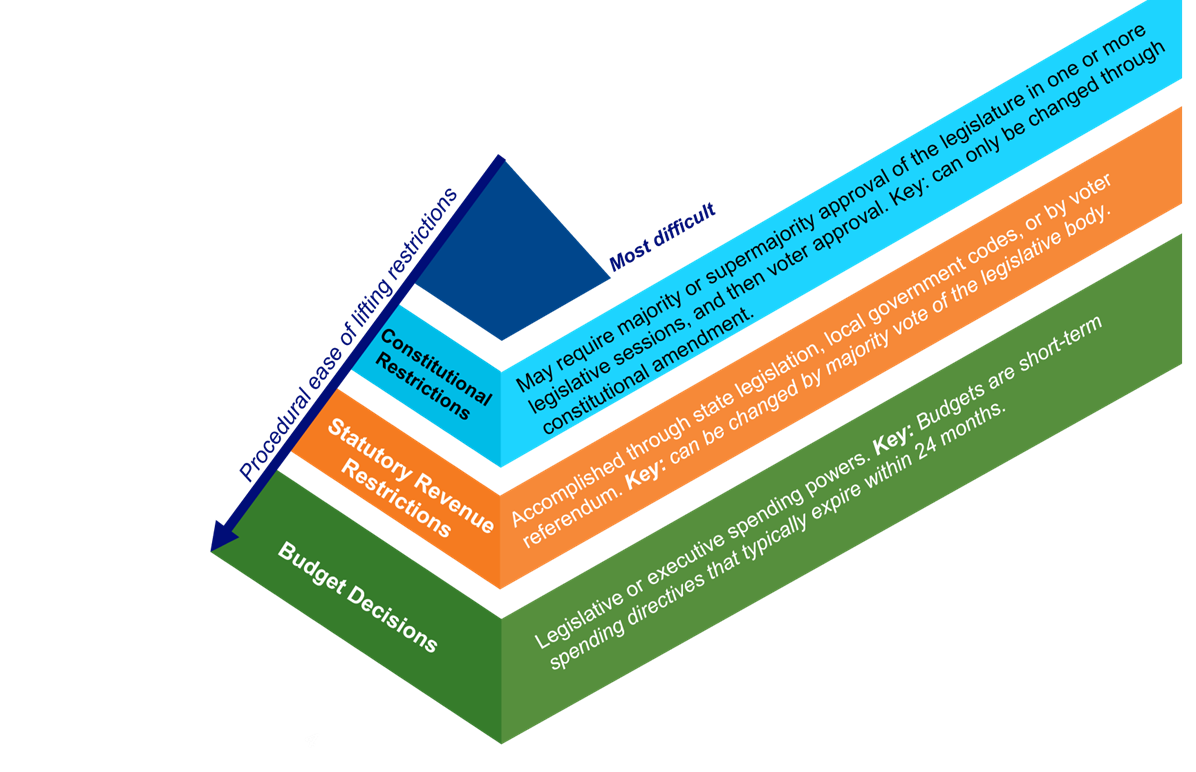

State governments use three primary methods to determine how revenue can be used: constitutional restrictions, statutory revenue restrictions, and budget decisions. In many states, these methods are used to dedicate most, if not all, of a state’s transportation revenue solely for transportation purposes or highway-related purposes. The ease with which each method can be enacted or repealed to restrict the use of revenue varies, along with the duration of that restriction.

First, constitutional restrictions involve amending the state constitution to restrict the use of certain revenue for transportation purposes. In states that have such a constitutional amendment, it is most often used to restrict fuel tax revenue for use on roads and bridges. A constitutional amendment is the most challenging restriction to implement or change because doing so often requires a two-thirds vote of the legislature, sometimes in multiple legislative sessions, and then an affirmative vote of the people.

Next, statutory restrictions require a legislature to pass laws that narrowly define how revenue can be spent. These restrictions are codified in statute and often only require a majority vote by the legislature; however, they exist in statute until they are repealed.

Finally, budget decisions are also used to direct where and how certain funds are used. In most states, legislatures develop and enact a state transportation budget, which codifies where and how transportation funds will be used. It operates the same as a statutory restriction; however, because budgets only bind the current legislature, a new legislature is free to develop and enact a new budget. Therefore, the restrictions developed through a budget process generally last two years. These constitutional, statutory, and budgetary restrictions on how transportation revenue sources can be spent are important to understand when evaluating options for RUC implementation.

When developing the implementation of a RUC system, it is important to understand the constitutional and statutory (or legal) restrictions on how various highway funding sources can be spent and who can collect the fees (e.g., vendors on behalf of the state). The legislature must decide where revenue from the RUC system will be directed and whether there should be any restrictions on the use of RUC revenues (e.g., all transportation projects or just roads and bridges). There tends to be broad public support for restricting transportation revenues and RUC to transportation projects. If there is already a constitutional provision or amendment restricting fuel tax revenue to transportation projects, changes may need to be made to ensure that RUC revenue is included in that constitutional guarantee. Generally, limitations on the use of revenue are not an obstacle to implementing a RUC program.

Check out the following building blocks to learn more:

As of 2022, all states except Alaska had some type of requirement that motor fuel taxes must be spent on transportation. Constitutional amendments limiting the expenditure of fuel tax revenue for highways are the most common spending restriction, with 24 states having passed such amendments. Most of these states also restrict the expenditure of other motor vehicle–related taxes and fees, especially vehicle and driver license fees. Nearly half of U.S. states (22 states) have constitutional restrictions barring the gas tax from supporting public transportation. Sixteen states have statutory restrictions on the use of fuel tax revenue.

Fewer restrictions on how transportation-related revenue is spent may allow for more policy options to be considered when implementing a RUC.

Check out the following building block to learn more:

Bonding restrictions could have an impact on RUC legislation. States should conduct a legal analysis to determine the potential impacts of constitutional and statutory restrictions on RUC legislation in their state. Additionally, states should complete revenue modeling to understand how to address projected revenue needs.

Check out the following building blocks to learn more:

Since your state does not bond against transportation revenue, there is no need to address the issues related to bonding against RUC revenue.

State requirements for the enactment of new taxes or tax increases vary. In some states, a simple legislative majority can approve a new tax and/or a tax increase, while in others, a supermajority is required. Further, the definition of supermajority varies among states. For example, supermajority can require a two-thirds, three-fifths, or three-fourths majority. Some states even require approval by voters. Understanding these tax enactment requirements is critical to determining how a RUC could interact with a state’s existing laws and, ultimately, be implemented.

In 34 states and Washington, D.C. (as of 2022), the legislature can enact new taxes or increase existing taxes with a simple majority vote. The table below shows that 16 states require a supermajority vote: Four states require a three-fifths majority, eight states require a two-thirds majority, and three states require a three-fourths majority. Most states’ supermajority requirements apply to all taxes, but there are exceptions in three states, as noted in the table. In Colorado, all new taxes or tax increases require voter approval, except in the case of emergencies.

The ability to pass RUC legislation is directly impacted by the legislative requirements to enact a new tax. Having RUC champions in the legislature, as well as knowledgeable staff who help legislators stay informed, work through the process, and address important questions and concerns related to RUC, can help with passing RUC-enabling legislation.

Check out the following building blocks to learn more:

In most cases where RUC revenues are used for general transportation purposes, RUC is likely to be considered a tax and not simply a fee (although in states such as Utah, RUC is currently considered a fee because it is paid in lieu of the alternative fuel vehicle fee).

Whether a charge is characterized as a tax or fee has statutory and constitutional implications. The power to tax is vested in the legislature, which has broad authority to do so. The authority to impose a fee is narrower in scope and invokes the government’s ability to regulate certain activities. While a fee is often more politically palatable, it may not always be an option for implementing a policy involving a financial levy that applies to nearly every person.

Performing a legal analysis may be important for determining which policy paths are available in your state.

Check out the following building block to learn more:

Vehicle safety or emissions inspections could be leveraged for a RUC by using the inspection data for RUC recording, reporting, and true-up. This would work particularly well for states that have an annual safety inspection that already includes odometer data collection because minimal changes would be required to existing processes.

Vehicle inspection requirements vary widely across the states, including the type of inspection, frequency, subject vehicles, and data collected. This guide focuses on whether the various existing state vehicle inspections can be leveraged for RUC. To evaluate this, inspections were sorted into the following categories:

As of 2022, 14 states required annual safety inspections where the vehicle’s odometer reading is collected as part of the inspection. Eighteen states either do not have any vehicle inspections, or have inspections that are insufficient for the purposes of RUC due to the infrequency of inspections and/or minimal vehicles subject to the inspections.

In states where they are required, emissions inspections are typically required every other year. New Jersey, Connecticut, and Washington, D.C., require emissions inspections for all vehicles, whereas other states with vehicle emissions inspections only require them for a geographical subset of vehicles. For states requiring emissions inspections for a geographical subset of vehicles, the utility of the inspections for RUC collection will vary based on the percentage of vehicles covered.

Additional RUC reporting options will need to be offered for vehicles not subject to vehicle inspections or in the years when a vehicle inspection is not required.

Check out the following building blocks to learn more:

Many states require vehicle owners to have regular vehicle inspections to ensure that vehicles conform to safety and emissions regulations and to help identify vehicles that may require repairs. In states where such inspections are required, they can potentially be leveraged to collect mileage data for a RUC program. States without these required inspections should explore other mileage reporting methods to use instead.

Check out the following building block to learn more:

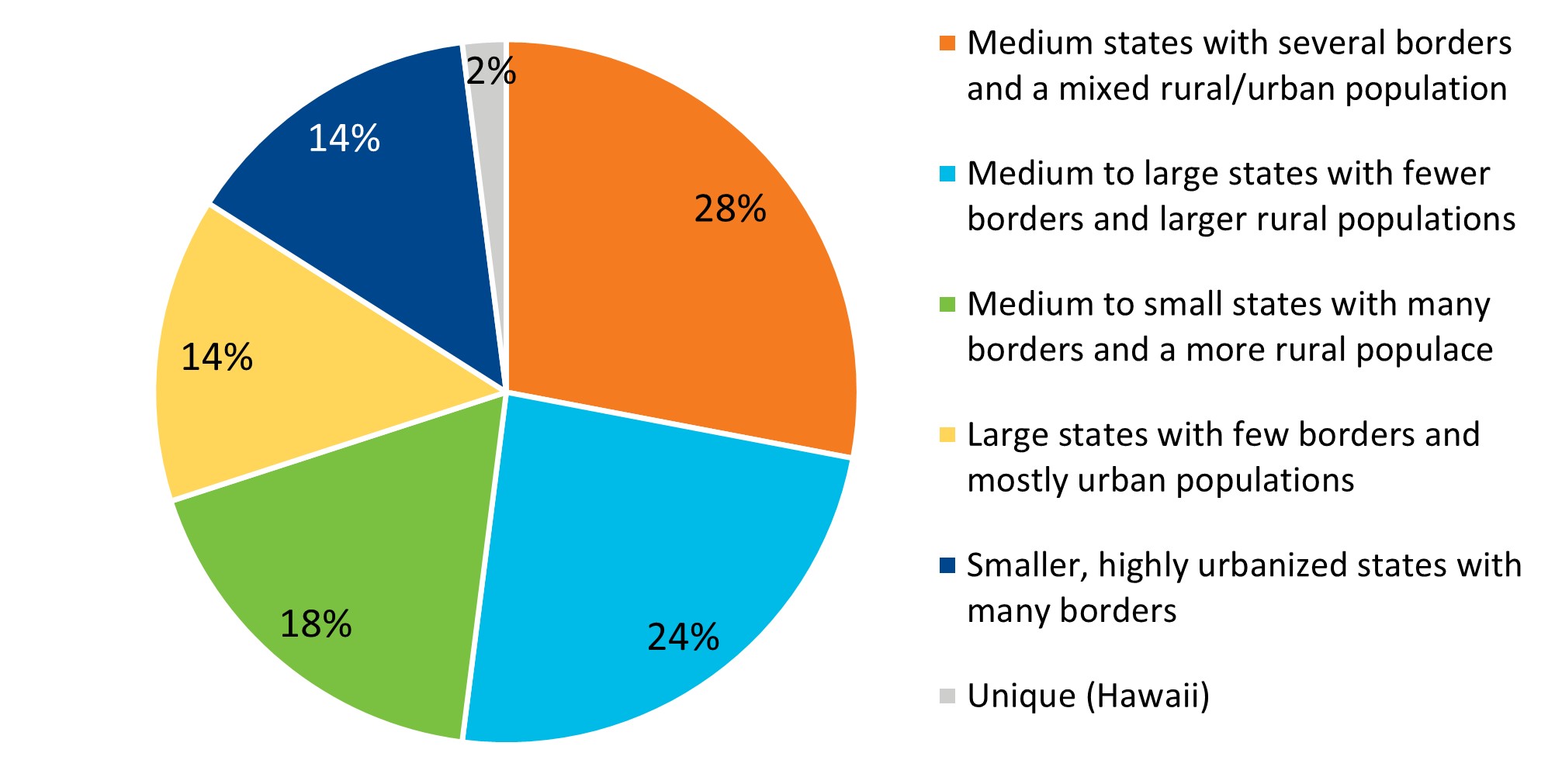

Common concerns raised by the public about a RUC are related to geographic equity. Many worry that rural drivers would end up paying more because they drive more miles or that people who have long commutes and limited or no access to public transportation will be penalized. Another concern is the ability of a RUC to capture revenues from out-of-state drivers. This consideration focuses on the geographic features of states, including urban and rural populations, and the potential for cross-border travel with other states and countries.

The framework for evaluating how a state’s geographic features could influence RUC implementation is primarily based on the state’s border-to-area ratio and rural/urban population percentages. For the purposes of this guide, the following categories were developed:

- Medium states with several borders and a mixed rural/urban population

- Medium to large states with fewer borders and larger rural populations

- Medium to small states with many borders and a more rural populace

- Large states with few borders and mostly urban populations

- Smaller, highly urbanized states with many borders

- Unique (Hawaii)

The figure below shows the percentage of states in each geographic category. The majority of states are medium states with several borders and a mixed rural/urban population (e.g., Kansas, Minnesota, Washington, Virginia) or medium to large states with fewer borders and larger rural populations (e.g., Iowa, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and Wyoming). Many Eastern states are medium or small states with many borders, which can mean more frequent cross-state travel. Indeed, cross-state travel is significant in the Eastern United States, where from 2018 to 2021, RUC pilots saw that 10% to 20% of participants’ miles were driven outside of their home state.

Research and communication about RUC must be sensitive to the geographic characteristics of the state because people who live in different geographic areas react differently to RUC and generally have concerns that are unique to their area. These geography-specific concerns need to be taken into consideration and require significant public education and outreach.

To account for the needs of rural drivers, for example, the technology in a RUC system could be used to charge only for miles driven on public roads, making miles driven on private farms and ranches free of charge. Additionally, public fear that RUC is inequitable for those with longer commutes may need to be addressed. The Distributional Impacts Analysis building block delves deeper into these geography-specific challenges and the strategies for addressing them.

Check out the following building blocks to learn more:

To understand whether or how different geographies may be affected by a RUC in your state, complete a distributional impacts analysis. If this evaluation identifies significant diversity between urban and rural areas, review the research materials provided for the affirmative response to this question.

Check out the following building block to learn more:

A significant challenge with the implementation of a RUC system is its interplay with other states. Some medium and smaller states have many borders and a higher potential for cross-state travel. A state must determine how critical it is to offer options for determining where miles are driven. Early multistate or regional coordination could be beneficial to a low-cost, harmonized solution for interstate issues around the collection and distribution of revenue from a RUC system.

The International Fuel Tax Agreement for motor carriers could provide a potential framework for RUC as it has helped relieve the burden of fuel tax reporting requirements on motor carriers and simplified fund reallocation between states.

Conduct an analysis of multijurisdictional approaches to understand which options might be available to your state.

Check out the following building block to learn more:

To understand how cross-border travel may impact RUC policy, review the research materials provided for the affirmative response to this question.

When transitioning a new policy like RUC from concept to implementation, the administering agency of government faces many organizational needs in order to stand up and operate the program. This dimension considers existing organizational structures, including the relationship between states’ motor vehicle administrators (often departments of motor vehicles or departments of revenue) and departments of transportation, the agencies collecting the revenue, and the technical capabilities of their systems that could potentially be used for RUC.

High-level research on each state’s organizational structure in 2022 revealed that in 17 states, the department of motor vehicles is part of the department of transportation. In all other states, the department of motor vehicles is part of another organization or is a stand-alone entity.

In most states, fuel tax revenue is collected by the department of revenue or taxation, and vehicle revenue is collected by the department of motor vehicles. In a few states, the department of transportation plays some role in revenue collection.

The Functional Analysis of Existing State Agencies’ Organizations building block can be conducted by each state to help identify the best state agencies to lead and support a RUC program and to determine what must be done to prepare these agencies for RUC. These agencies include not just the department of motor vehicles or department of transportation but also related agencies involved in revenue collection, such as the department of revenue or taxation, the department of treasury, and the department of information technology.

Any government evaluating the establishment of a new RUC program must review core organizational needs to help identify the agencies best suited for various RUC functions, including program oversight and management, and then design an organizational structure that meets agency needs.

As of 2022, in Oregon and Utah, the departments of transportation have been responsible for RUC program management. In Virginia, the responsibility has been placed with the department of motor vehicles. In most cases, departments of transportation play an important role in RUC programs because they are the main benefactors of RUC collection. Other agencies, such as departments of motor vehicles or departments of revenue, may collect the vehicle registry data and fees. Separate agencies may also administer commercial and noncommercial functions. In cases in which the functions are combined, RUC implementation may be easier. When separate organizations are involved, there may be more organizational issues or hurdles to overcome. The building blocks provided in this guide make a distinction between the lead RUC agency and the implementing RUC agency to clearly identify the agency responsible for each function.

Assessing the technical capabilities and age of impacted agencies’ information technology systems is also important. Older systems may need to be modernized or interfaced with third-party solutions to support a new RUC program. Any opportunities to share the cost of collection with other programs should be evaluated, such as by developing back-end systems that support other programs.

Check out the following building block to learn more:

The Functional Analysis of Existing State Agencies’ Organizations building block can be conducted to help identify the best state agencies to lead and support a RUC program and to determine what must be done to prepare these agencies for RUC. These agencies include not just the department of motor vehicles or department of transportation, but also related agencies involved in revenue collection, such as the department of revenue or taxation, the department of treasury, and the department of information technology.

Check out the following building block to learn more:

SELF-ASSESSMENT PART 3: Challenges and Strategies

CHALLENGES AND STRATEGIES

These challenges and strategies, and associated building blocks, are most relevant for the RUC Lead Agency during the Research and Planning stage. The challenges are organized into analytical, design, and policy categories, and each challenge is addressed by one or more strategies.

- Analytical Challenges: Many challenges to RUC acceptance are based on misperceptions or assertions not supported by evidence. Analysis can serve a “myth-busting” function by providing decision-makers with objective results that rebut a question, concern, or objection. However, facts may not sway an entrenched opinion.

- Design Challenges: Many objections to RUC are legitimate and based in fact. In these cases, changes to the technical or policy design of RUC can ameliorate the problem and help decision-makers overcome barriers.

- Policy Choices: Policy choices sometimes present themselves as challenges. In these cases, decision-makers need actionable information—like the pros and cons of each choice, and sometimes even advice on how to decide—to inform their ultimate decisions.

The strategies presented are not mutually exclusive. In fact, the proposed strategies are complementary, and it may be helpful to engage several or all strategies to overcome each challenge in a given state. Where relevant, strategies for overcoming these challenges reference the RUC system stages, activities, and building blocks that are described in more detail in the RUC building blocks.

ANALYTICAL CHALLENGES

Equity by Geography

A common misperception holds that RUC will disproportionately burden rural drivers since rural trips tend to be longer than urban trips. Although this concern arises wherever RUC is proposed, the concern may be greater in states with large urban-rural divides. For example, San Francisco, California, has a significantly different urban form than Vacaville, California. In states like Montana or Wyoming, urban centers have relatively low population densities, so the experiences of urban and rural drivers may not be significantly different.

Strategy 1: Conduct a thorough quantitative analysis using National Household Travel Survey data and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency–reported fuel economy estimates. Stratify the data by urban and rural geographies (and possibly others, such as suburban).

Since lower-income and rural households tend to have older vehicles that are less fuel efficient, a passenger vehicle RUC that does not vary by vehicle characteristics slightly improves vertical equity, assuming a flat, revenue-neutral RUC rate. A RUC has been found to slightly improve urban vs. rural equity by shifting some of the burden from rural to urban payers. The level of improvement, however, has been slight. Exact results will vary by state. To conduct this analysis of interstate commercial vehicles, data from the International Fuel Tax Agreement Clearinghouse and the International Registration Plan Data Repository can be accessed. Some jurisdictions may gather this information from intrastate vehicles as well. These data would contribute to a more thorough understanding of the impacts of RUC on the commercial motor vehicle industry.

Strategy 2: Use geographically representative participants in pilot testing.

Actual on-road experience in the local urban form may be more convincing to some than a desktop exercise. Compare a revenue-neutral RUC to what would have been paid in gas tax and stratify by region. Note that rural participants who drive high fuel-efficiency vehicles may pay more under RUC than they do under the fuel tax because of their higher-than-average driving distances and lower-than-average fuel tax payments. This minority of rural dwellers would pay slightly more per mile under a RUC than they do under a gas tax. Most rural participants are likely to pay less under RUC since they tend to drive less fuel-efficient vehicles, and therefore make relatively high fuel tax payments. Vehicles with fuel economies that deviate furthest from the mean MPG value on which a revenue-neutral RUC rate is based would see the biggest difference in annual RUC payments relative to the gas tax. Interestingly, this analysis of MPGs and distances driven applies equally to commercial and noncommercial vehicles. Heavy-duty commercial vehicles accruing higher-than-average daily miles with lower fuel efficiency will likely pay less under a RUC system that is designed to be revenue-neutral.

- Phase: Research and Planning

- Activity: Demonstrate Possible Approaches

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Strategy 3: Educate the public and stakeholders about the impacts of RUC.

Public opinion research, including focus groups, interviews, and surveys, can be used to capture and understand the public’s main concerns, which can inform messaging that will resonate with the public and help craft the optimal political strategy. Targeted education and opinion-gathering efforts aimed at commercial and noncommercial vehicle drivers will help to identify the particular issues and concerns pertaining to different driver types.

Using the vision and objectives as a starting point, and informed by public opinion research, the communication teams of the lead and implementing RUC agencies develop the core messages. Messaging should address equity and fairness concerns, specifically focusing on urban vs. rural equity.

- Phase: Research and Planning

- Activities: Stakeholder and Public Engagement; Research Policy

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Equity by Income

It is a common misperception that RUC will disproportionately burden lower-income drivers.

Strategy 1: Conduct a quantitative analysis using National Household Travel Survey data and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency–reported fuel economy estimates. Stratify by income.

Since lower-income and rural households tend to have vehicles that are older and less fuel (shown at a national level in National Household Travel Survey data), introducing passenger vehicle RUC slightly improves vertical equity as well as rural versus urban equity. Exact results will vary by state.

- Phase: Research and Planning

- Activity: Research Policy

- Refer to the following building block:

Strategy 2: Use participants from various income brackets in pilot testing.

Actual on-road experience may be more convincing to some than a desktop exercise. Compare a revenue-neutral RUC to what would have been paid in gas tax and stratify by income. Note that lower-income participants who drive high fuel-efficiency vehicles may pay more under RUC than they do under the fuel tax because of their lower-than-average fuel tax payments. This minority of lower-income drivers would pay slightly more per mile under a RUC than they do under a gas tax. Most lower-income participants are likely to pay less under RUC since they tend to drive less fuel-efficient vehicles and, therefore, make relatively high fuel tax payments. Vehicles with fuel economies that deviate furthest from the mean MPG value on which a revenue-neutral RUC rate is based would see the biggest difference in annual RUC payments relative to the gas tax.

- Phase: Research and Planning

- Activity: Demonstrate Possible Approaches

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Strategy 3: Educate the public and stakeholders about RUC.

Baseline public opinion research using focus groups, interviews, and surveys helps to determine the public’s main concerns. This research can inform messaging that resonates with the public and addresses equity and fairness concerns, specifically those relating to income.

- Phase: Research and Planning

- Activities: Stakeholder and Public Engagement; Research Policy

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Equity by Vehicle Type

Some have expressed concern that a flat RUC charge would unfairly impact certain vehicle types and contend that heavier vehicles do more damage to the roadway and so should pay more per mile in RUC. Roads are engineered such that vehicles under about 10,000 pounds have equivalent impacts on pavement and congestion. Weight becomes a factor for medium-duty vehicles (10,001 to 26,000 pounds) and heavy-duty vehicles (above 26,000 pounds).

Strategy 1: Conduct a highway cost allocation study in the state, or leverage data that will be generated in the forthcoming federal highway cost allocation study authorized and funded by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

Few states conduct cost allocation studies because they can be controversial; however, the results can inform policymaking. For example, the results can be used to determine the cost share of highway maintenance and operations that should be borne by different vehicle weights or classes. Recent research by The Eastern Transportation Coalition found that it is not appropriate to charge heavy-duty vehicles and passenger vehicles the same rate, nor can heavy-duty vehicle groups be effectively distinguished by MPG bands for rate-setting purposes. Distinction by weight class is the most directly proportionate to roadway maintenance costs. However, the difference in road wear caused by the lightest and heaviest vehicles within the light-duty passenger vehicle class (i.e., vehicles weighing less than 10,000 pounds) is negligible. Variable rates among light-duty vehicles are not recommended on the basis of weight alone because there is no engineering or economic evidence to support the perception that their road impact costs vary by weight.

- Phases: Research and Planning; Setup

- Activities: Research Policy; Administrative Rules and Activities

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Strategy 2: Reach out to medium-duty and heavy-duty vehicle stakeholder groups to discuss and better understand their concerns, to share information about RUC, and, once an analysis has been conducted, to share the potential impacts on heavy-duty vehicles.

Consider opportunities for simplifying reporting requirements for heavy-duty vehicles, such as combining registration fees and other fees with a RUC. Messaging should address vehicle equity and fairness concerns, including equity by vehicle class and type.

- Phases: Research and Planning; Setup

- Activities: Stakeholder Engagement; Research Policy; Administrative Rules and Activities

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Impact on Emissions

Some people have expressed concern that RUC unfairly impacts low-emissions vehicle types, specifically electric vehicles, hybrids, and high-efficiency gas-powered vehicles, which would cost more per mile to operate under a RUC than they do under the gas tax. For those expressing concern, it seems contradictory for the state to both promote the adoption of electric vehicles and charge electric vehicles for road usage through a RUC system.

Strategy 1: Explicitly state that the goal of a RUC is to create a sustainable funding mechanism for transportation infrastructure.

This does not preclude other environmental policy tools from coexisting with RUC. Policies, such as tax credits for the purchase of an electric vehicle or a per-mile carbon tax, can be implemented separately from RUC. However, the RUC itself is a funding mechanism only. Moreover, the saliency of RUC charges to users is more likely to change driving behavior than gas taxes, even if the total amount paid is roughly the same on an annual basis.

- Phases: Research and Planning

- Activities: Stakeholder Engagement; Research Policy

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Strategy 2: Conduct a quantitative analysis of electric vehicle cost of ownership and market trends using National Household Travel Survey data, fuel prices, Bureau of Labor Statistics data, and other data.

While, on a per-mile basis, gas taxes are determined entirely by vehicle fuel efficiency, households drive a different number of miles annually, and these differences in total vehicle miles traveled influence total gas tax costs more than fuel efficiency. The number of miles traveled annually by households varies widely, but the range of fuel efficiency for vehicles is relatively narrow. Since fuel taxes are a small percentage of the total price of gasoline, electric vehicles remain cheaper to operate on a per-mile basis than their gas-powered counterparts under a RUC system. When compared to the fuel tax rate, oil prices play a much bigger part in the price of fuel. A RUC with a revenue-neutral rate can be calculated by dividing the current gas tax rate by the average fuel economy of the vehicle class. At that revenue-neutral RUC rate, electric vehicles, hybrids, and other high-efficiency vehicles would retain most of the cost savings of reduced fuel use. Additionally, electric vehicles will likely reach price parity with gas-powered vehicles by the time a fully realized RUC program could realistically be implemented.

- Phase: Research and Planning

- Activity: Research Policy

- Refer to the following building block:

Strategy 3: Reach out to environmental stakeholder groups to discuss and better understand their concerns; share information about RUC; and discuss the bottom-line savings for fuel-efficient vehicles, as demonstrated in Strategy 2.

Messaging should address vehicle equity and fairness concerns, including equity by vehicle engine type. As electric commercial vehicles become more common, these outreach efforts should include analyses of medium- and heavy-duty commercial electric vehicles.

- Phase: Research and Planning

- Activities: Stakeholder Engagement; Research Policy

- Refer to the following building blocks:

DESIGN CHALLENGES

Cost of Administration

While the gas tax is not a sustainable funding mechanism, it is administratively efficient. In most states, fuel taxes are imposed on fuel distributors and suppliers rather than directly on motorists at the pump. This method of collection limits the number of taxpayers to a few dozen or a few hundred companies rather than hundreds of thousands or millions of individual drivers. Economic research completed by Justin Marion and Erich Muehlegger in “Fuel Tax Incidence and Supply Conditions” indicates that that “state gasoline and diesel fuel taxes are on average fully and immediately passed on to consumers” after any change in the tax rate. In other words, companies immediately pass along the fuel costs to motorists even though it is technically levied on distributors, not directly on drivers. Since the gas tax is typically included in the total price of fuel, and not as a separate line item, the gas tax is “invisible” to many drivers.

The cost to administer fuel excise taxes is estimated to be between 0.9% and 3%. The Waka Kotahi New Zealand Transport Agency, which collects and manages all RUC revenues in New Zealand, estimates that a RUC system is roughly twice as expensive to administer as the fuel excise tax. Actual costs experienced by U.S. states will depend on local circumstances, such as the scale of the RUC program or the presence of existing systems and processes that a RUC system could leverage to reduce costs (i.e., annual odometer readings at vehicle inspections, mileage reporting for interstate commercial motor carriers). For example, Oregon’s RUC program provides 40% of revenue collected to third-party commercial account managers. However, this program serves fewer than 1,000 vehicles, and reduced costs are a prerequisite to program expansion.

In the United States, many states used some form of a weight-distance tax for heavy-duty trucks during the 20th century. Most state weight-distance taxes were discontinued because of high administrative costs or lawsuits, or threats of lawsuits, from the trucking industry. As of 2022, four states have a weight-distance tax for heavy-duty vehicles: Oregon, New York, Kentucky, and New Mexico. Estimates for the cost of administration of these programs vary widely, ranging from as low as 3% to as high as 20% of gross revenues. The relatively high cost of administration can be attributed to the burdensome manual reporting and recordkeeping required, given the technology available at that time, as well as the structure of some programs that required weight reporting on a per-trip basis.

Reporting and payment can be simplified with in-vehicle telematics or online self-reporting and payment portals, while recordkeeping and billing can be streamlined using shared databases between state motor vehicle registries and departments of revenue or by using a commercial account manager.

Tolling, another form of revenue collection for road, bridge, and tunnel infrastructure, tends to have a higher cost of collection than both the gas tax and RUC. Precise data on the cost of administration in the tolling industries is usually not readily available. Many tolling agencies in the United States do not release financial data because it may impact the cost of capital for upcoming bond issues, bond covenant requirements, intergovernmental agreements among toll agencies, or stock prices for privately financed and publicly traded tolling agencies. However, a report by the Washington State Department of Transportation examined the collection costs of several toll systems using electronic toll collection and found that costs ranged from 14% to 20% of revenue.

Although RUC administrative costs will likely decline as systems scale and mature, RUC will likely have higher administrative costs than the gas tax, regardless of the mileage reporting method used. The success of a RUC program depends, in part, on keeping the cost of administration low. As a RUC program grows, economies of scale and cost sharing with existing programs reduce administrative costs over time.

Strategy 1: Offering manual mileage reporting as a foundation for RUC can keep costs of collection low.

A manual approach is a low-cost way to build the necessary systems and begin revenue collection. For commercial motor carriers that already report mileage to the state, integrate RUC reporting with the current reporting system to streamline the process for both motor carriers and the state.

- Phase: Research and Planning

- Activity: Study Organizational Structure and Readiness

- Refer to the following building block:

Strategy 2: Leverage the private sector for expertise in mileage reporting technology, account management, and customer service.

The private sector invests and continually updates their systems and technologies in order to provide the latest and best approaches, relieving government of these costs. In New Zealand, private sector enhancements have come at zero cost to the government, which runs only a nontechnology manual system. Although Oregon has adopted a model similar to New Zealand’s, the market size remains small, so the state must incentivize market participation for passenger vehicles; a heavy-duty vehicle service provider operates in Oregon at no cost to the state. Encouraging competition among vendors will spur innovation and keep costs down.

- Phases: Setup; Transitioning and Growing

- Activities: Vendor Market Design and Procurement; Ongoing System Innovation

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Strategy 3: Requiring prepayment of RUC, possibly through an electronic wallet payment, simplifies program administration and reduces the likelihood of evasion and the level of enforcement needed.

Requiring prepayment provides cash flow to the agency. It also reduces transaction costs by eliminating the need for invoicing and reminders for unpaid accounts, though account statements may still be needed. When a specific number of miles is prepaid, there generally needs to be a true-up procedure by which the number of miles driven is reconciled with the number of miles prepaid; this true-up procedure may occur quarterly or annually. Some tax collection and administration systems may need to be reconfigured to support prepayment. While the notion of prepaying for RUC may be less politically acceptable than post-payment, the gas tax is also a prepayment model— vehicle owners pay the tax before they expend the fuel to drive on the roads. This analogy can make RUC prepayment more acceptable, especially since one of its policy purposes is to replace the gas tax.

- Phase: Research and Planning

- Activity: Study Organizational Structure and Readiness

- Refer to the following building block:

Strategy 4: Aligning incentives between the agencies collecting and dispersing funds can minimize costs.

As existing RUC programs have shown, alignment between the agency collecting funds and the agency benefitting from the collection of funds can ensure the right incentives are in place to minimize the cost of administration. In addition, collaboration on activities can streamline efforts and reduce costs. For example, one agency can collect not just state RUC but potentially also other vehicle-related fees, including on behalf of other jurisdictions such as the federal government and local jurisdictions. Consolidating similar functions within a single agency, such as public outreach, communications, back-office systems, account management, and customer service, can help to reduce the costs attributed to RUC by itself.

- Phase: Research and Planning

- Activity: Study Organizational Structure and Readiness

- Refer to the following building block:

Strategy 5: Starting with a small-scale RUC program allows the administering agencies to set up systems, collect revenue, and interact with customers in a relatively low-risk, low-stakes way.

Gradual transitions are more practical and less costly. For now, the fuel tax remains the most efficient transportation tax in the country. Continuing to rely on the fuel tax for the majority of registered vehicles that will continue to burn fuel for at least another decade allows the state to do the following before transitioning to large-scale RUC revenue collections:

- Ensure the RUC system is as cost-effective as possible.

- Allow time to establish rules.

- Build and test processes and systems.

- Train staff.

- Grow familiarity with customers.

A rapid transition to a large-scale RUC program could result in costly mistakes.

- Phase: Research and Planning

- Activity: Research Policy and Politics

- Refer to the following building block:

Data Security and Privacy Protection

One of the biggest challenges facing RUC implementation is assuring the general public that any data collected on road usage will be protected and that personally identifiable information will not be shared with third parties. Drivers also need assurances that the government is not actively monitoring their travels. A successful RUC program needs both technical/operational measures and legal measures to ensure privacy.

Strategy 1: Conduct a RUC legal analysis.

Does the state have privacy laws? Will new privacy measures be needed for RUC? Take legal, technical, and operational measures to ensure privacy rights, and include privacy rights in RUC-enabling legislation. Investigate how privacy laws differ for commercial and noncommercial operations.

- Phase: Research and Planning

- Activity: Research Policy and Politics

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Strategy 2: Provide a range of mileage reporting and technology options to give drivers control of their privacy decisions.

Noncommercial drivers can choose whether to share their personal driving information through the selection of mileage reporting options (e.g., location-based, non-location-based, or odometer reading). Those with significant privacy concerns can select a low-technology mileage reporting option, such as odometer reporting. Another option is to offer a relatively high flat fee to opt out of reporting miles driven altogether. Those who are more comfortable with technology can select a location-based mileage option, which often includes several additional premium features offered by commercial account managers for personal use (e.g., trip logs, driving scores, safe zones). Commercial drivers’ choices in reporting mechanisms may be limited by the other taxes and fees they are required to remit. Review the commercial motor vehicle tax and fee structure to offer commercial drivers choices to protect their privacy as much as possible while fulfilling their reporting obligations.

- Phases: Research and Planning; Setup

- Activities: Demonstrate Possible Approaches; System Design (State and Vendor)

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Strategy 3: Provide options on who collects and processes data.

Consider using third-party vendors or private sector experts to collect the number of miles driven and manage the data and payments to help reduce privacy and data security concerns. Again, this strategy may vary for some commercial motor vehicle operators, who are used to sharing more information about their locations and travel due to legal and regulatory requirements. Streamlined reporting may be more important to that sector.

- Phases: Research and Planning; Setup

- Activities: Demonstrate Possible Approaches; System Design (State and Vendor)

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Strategy 4: If opting for a vendor system, specify system requirements so that the state only receives aggregated and anonymized data that do not include personally identifiable information, regardless of the technology option chosen.

These data generally include the total number of miles driven, the amount of fuel consumed (if applicable), and the net RUC amount owed. Additionally, system requirements can dictate that all personally identifiable information be purged from the RUC system after a stipulated number of days have elapsed following payment.

- Phases: Research and Planning; Setup

- Activities: Demonstrate Possible Approaches; System Design (State and Vendor)

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Strategy 5: Educate the public and stakeholders about RUC.

Baseline public opinion research using focus groups, interviews, and surveys helps to determine the public’s main concerns, which can help inform messaging that will resonate with the public and help craft the optimal political strategy. Commercial and noncommercial educational outreach may be necessary to address the disparate concerns of these populations.

Using the vision and objectives as a starting point, and informed by public opinion research, the communication teams of the lead and implementing RUC agencies develop the core messages. Reassure the public through messaging about strong privacy policies. Never use the word “tracked” when referring to mileage reporting.

- Phase: Research and Planning

- Activities: Stakeholder and Public Engagement; Research Policy

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Interoperability Among Federal, State, and Local Jurisdictions

States will differ in their approach to implementing RUC. It is likely that motorists will pay an account manager or agency in their home state, regardless of where the miles were driven. Some method of reconciling RUC collected in different jurisdictions will be necessary. Several strategies could be deployed to address this issue. Each comes with operational and enforcement challenges, costs, and benefits that can be examined to inform choices about which, if any, to deploy.

Strategy 1: Distance-based charge for motorists with location-based mileage reporting.

With this strategy, motorists are assessed a charge based on the number of miles driven in a given jurisdiction. For motorists with location-based mileage reporting technologies, it is possible to directly measure miles driven in each jurisdiction and report that mileage to either a state-managed RUC agency or a RUC account manager. The RUC agency or account manager would then remit the out-of-state mileage to the appropriate state for billing or bill the motorist and remit the payment to the owed state.

- Phases: Research and Planning; Setup; Transitioning and Growing

- Activities: Research Policy; Administrative Rules and Activities; Study Organizational Structure and Readiness; Collaboration with Other Jurisdictions

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Strategy 2: Shadow charge.

Rather than directly levying RUC on visitors, states reconcile funds based on some estimate of the amount of visitor-generated vehicle miles traveled.

- Phases: Research and Planning; Setup; Transitioning and Growing

- Activities: Research Policy; Administrative Rules and Activities; Study Organizational Structure and Readiness; Collaboration with Other Jurisdictions

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Strategy 3: Distance-based and fuel-based.

Jurisdictions retain their motor fuel tax to capture miles driven by out-of-state visitors (assuming they purchase fuel in-state) and refund fuel taxes paid by in-state motorists who already pay the RUC. This option would not directly charge out-of-state visitors for road usage. If no fuel is purchased in-state, nothing would be collected from out-of-state drivers.

- Phase: Transitioning and Growing

- Activity: Collaboration with Other Jurisdictions

- Refer to the following building block:

Strategy 4: Time-based.

Jurisdictions may offer short-term passes (e.g., a day or a week) for unlimited miles to offer visitors an easy way to report travel.

- Phase: Transitioning and Growing

- Activity: Collaboration with Other Jurisdictions

- Refer to the following building block:

Strategy 5: App-based odometer reporting.

Jurisdictions may offer visitors a means to report their odometer at the approximate time of state entry and exit; odometer images should never be required while driving. The RUC could be paid when a vehicle leaves the state. Vehicles would need to report their license plate at the time they report their odometer, and automatic license plate recognition cameras could ensure that vehicles have registered. While there are known operational challenges with this strategy, some states that are currently conducting RUC research and pilots are considering app-based odometer reporting as one potential option.

- Phase: Transitioning and Growing

- Activity: Collaboration with Other Jurisdictions

- Refer to the following building block:

Strategy 6: Commercial motor carriers.

Commercial motor carriers subject to International Fuel Tax Agreement and International Registration Plan reporting currently have mechanisms in place to report mileage traveled in each state. For those carriers, the existing technology could be used to report miles for RUC. For smaller and intrastate commercial motor carriers, similar reporting requirements could be implemented so that all commercial motor carriers within a state would be subject to the same regulations. Interoperability of these reported miles could be achieved through one of the existing clearinghouses, through a vendor-based solution, or through a new clearinghouse solution designed with RUC at its core.

- Phase: Transitioning and Growing

- Activity: Collaboration with Other Jurisdictions

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Integration with Tolling and Congestion Pricing

Many states operate tolling systems that use in-vehicle transponders tied to an account with stored banking card information to charge drivers for each transaction. While tolling (discrete) and RUC (continuous) are functionally and operationally different, drivers may perceive the two systems as similar or view RUC as an additional inconvenience. Compatibility between the two systems may increase public acceptance of RUC and have the added benefit of improving collection rates and reducing operational costs for both RUC and tolling. Several states are studying the compatibility of the two, including Oregon.

A RUC system that uses location-based, in-vehicle mileage reporting devices is well-positioned to leverage the technology to also collect congestion charges during certain times of the day or in certain locations. However, congestion charging initially may be a more controversial policy than RUC because it represents a new cost to motorists on top of a RUC or gas tax, rather than simply replacing the gas tax. Public acceptance of congestion pricing tends to increase over time once the benefits are made apparent to the general public.

Strategy 1: Develop a strategy for technical and business/financial interoperability with the other pricing mechanism(s).

Technical interoperability means systems can communicate with each other with a common understanding of data. Business/financial interoperability means that two entities have established a formal business relationship, including plans for transferring funds with each other. To achieve interoperability, two entities must decide on technical data structures and protocols for technical interoperability as well as policies for business/financial interoperability.

- Phase: Transitioning and Growing

- Activity: Collaboration with Other Jurisdictions

- Refer to the following building block:

Strategy 2: If there is long-term interest in integrating RUC with congestion charging or tolling, ensure the architecture supports the addition of in-vehicle, location-based devices (e.g., native telematics or On-Board Diagnostic-II plug-in).

Vehicles without a location-based device will need to pay for tolls and congestion charges using another mechanism.

- Phase: Transitioning and Growing

- Activity: Collaboration with Other Jurisdictions

- Refer to the following building block:

Compliance and Enforcement

As the gas tax is built into the price paid at the pump and is “invisible” to many drivers, there is little opportunity for evasion. RUC, however, requires some active participation from drivers via processes like enrollment, reporting, and payment. Because of this, there is greater opportunity for evasion, intentional or otherwise. Some mileage reporting methods, such as self-reported mileage, may have a greater potential for evasion.

Strategy 1: Design the RUC system for compliance to reduce evasion.

- Phase: Setup

- Activity: Administrative Rules and Activities

- Refer to the following building block:

Strategy 2: Make the system simple and easy to use.

Use clear, simple language to explain requirements and include features to support all common-use cases, such as buying or selling a vehicle from a private or public dealer or driving out of the RUC jurisdiction.

- Phase: Setup

- Activity: Administrative Rules and Activities

- Refer to the following building block:

Strategy 3: Offer multiple mileage reporting methods and payment plans to accommodate the needs of different driver profiles and budgetary constraints.

- Phases: Research and Planning; Setup

- Activities: Demonstrate Possible Approaches; Administrative Rules and Activities

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Strategy 4: Focus on constructive work with initially noncompliant drivers to encourage active participation rather than punitive measures.

Build empathy through features such as grace periods and proactive communication.

- Phase: Setup

- Activity: Administrative Rules and Activities

- Refer to the following building block:

Strategy 5: Consider the costs versus benefits when designing an enforcement system.

Voluntary compliance with taxes and fees depends on a range of factors, including taxpayer understanding and fairness. The integrity of any tax or fee depends on public trust, which in turn depends on substantial compliance. However, an enforcement system that catches and penalizes every violation would be very costly and potentially counterproductive because it hurts public acceptance of RUC.

- Phase: Setup

- Activity: Administrative Rules and Activities

- Refer to the following building block:

Strategy 6: Educate the public and stakeholders about RUC.

Public acceptance can increase voluntary compliance.

- Phase: Research and Planning

- Activities: Stakeholder Engagement; Research Policy

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Strategy 7: Maintain fuel taxes during the transition period.

While the fuel tax is in place, there is little motivation for evasion by drivers paying the fuel tax. This is because evasion will not save them much money, since they will not receive the fuel tax credits owed if they evade. During the transition, monitor compliance and make enforcement adjustments over time.

- Phases: Setup; Transitioning and Growing

- Activities: Administrative Rules and Activities; Transition Strategy Development

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Location-Based Mileage Reporting

Location-based mileage reporting methods, such as location-based On-Board Diagnostic-II plug-in devices or vehicles with native telematics technology, offer some enhanced RUC system capabilities and operational benefits to the state, as well as greater convenience to drivers over low- or no-tech mileage reporting options. Some of these benefits include the following:

- Automatically exempts non-taxable miles, such as miles driven on private roads or out of state. This simplifies the user experience for drivers who frequent non-RUC-liable roads. These drivers would not have to manually keep track of exempt miles, reducing the need for audits as geolocated miles would be more challenging to manipulate than self-reported exempt miles. (See challenges around exemptions, credits, and refunds as well as strategies for overcoming these challenges.)

- Mileage reporting is automatic and secure. This reduces the administrative burden placed on drivers and could reduce enforcement and auditing costs for the state because automated mileage reporting methods are more difficult to manipulate than manually reported mileage. (See challenges around the user experience and compliance and enforcement as well as strategies for overcoming these challenges.)

- Creates the opportunity to align RUC with other efforts, including tolling and congestion pricing. These synergies may include tolling or the opportunity to leverage the RUC system to implement other policies, like cordon pricing, that depend on real-time vehicle location. (See challenges around integration with tolling and congestion pricing and around flexibility for policy adaptation as well as strategies for overcoming these challenges.)

While convenient, location-based mileage reporting methods are not without their challenges. While the price of location-based mileage plug-in reporting devices may come down at scale, they come at some cost to the driver, while other mileage reporting methods have no up-front costs to the driver. Unless drivers frequently travel out of jurisdiction, the cost of the plug-in devices may be a barrier to widespread adoption.

Additionally, vehicles manufactured before 1996 and some electric vehicles do not have On-Board Diagnostic-II ports. Native telematics are only available in select newer vehicles and are not typically optimized by manufacturers for RUC mileage reporting. Many drivers are not comfortable sharing location data with either the state or a commercial account manager, regardless of their personal needs or their vehicle’s compatibility.

Strategy 1: Support user choice in mileage reporting methods so drivers can interact with RUC in a way that suits their needs and preferences.

Drivers with vehicles that do not have native telematics and do not support plug-in devices and drivers with significant privacy concerns can select a low-technology mileage reporting option, such as odometer self-reporting. Drivers who would benefit from location-enabled mileage reporting can opt in if they choose.

- Phase: Research and Planning

- Activity: Demonstrate Possible Approaches

- Refer to the following building block:

Strategy 2: Provide options on who collects and processes location-aware mileage data.

Using third-party vendors or private sector experts to collect the number of miles driven and manage the data and payments can also help reduce privacy and data security concerns.

- Phase: Research and Planning; Setup

- Activity: Technology Analysis and Definition of Viable Operational Concepts

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Strategy 3: Reassure the public through messaging of strong privacy policies.

Never use the word “tracked” when referring to mileage reporting.

- Phase: Research and Planning

- Activities: Stakeholder Engagement; Research Policy

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Scalability of Systems

The most efficient and cost-effective way of setting up a small-scale RUC system may not necessarily be practical or economical at scale. While a manual mileage reporting approach is a low-cost way to build the necessary systems and begin revenue collections, for example, higher-tech options that cost more up-front may provide features needed to keep costs low at scale.

Strategy 1: Consider how the fully realized RUC program should be structured during the start-up and transition phases.

A transition strategy should lay out, in advance, the final end state to which the program aspires to ensure steps taken in transition lead to the goal rather than a dead end. The optimal transition pathway for expanding a small initial RUC program to a full RUC program over time depends on the preferred final RUC system delivery configuration.

- Phase: Research and Planning; Transitioning and Growing

- Activities: Research Policy; Transition Strategy Development; Transition Strategy Execution and Optimization; Ongoing System Innovation

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Strategy 2: Consider the cost of administration and ease of enforcement of the preferred mileage reporting method at scale when selecting a mileage reporting method.

Some jurisdictions may already have the systems and processes in place (e.g., mandatory annual vehicle inspections) to efficiently collect mileage data at scale, while others may have to rely on higher-tech options like On-Board Diagnostic-II plug-in devices.

- Phase: Research and Planning

- Activity: Study Organizational Structure and Readiness

- Refer to the following building block:

Strategy 3: Leverage the private sector for expertise in mileage reporting technology, account management, data security, and customer service.

The private sector invests and continually updates their systems and technologies in order to provide the latest and best approaches, relieving government of these costs.

- Phase: Setup; Transitioning and Growing

- Activities: Vendor Procurement; Ongoing System Innovation

- Refer to the following building blocks:

User Experience

As the gas tax is paid at the pump during each fill-up and is not generally shown as a separate line item on signs or receipts, it is “invisible” to many drivers. A RUC, on the other hand, requires some action by drivers to report mileage and pay mileage fees. New requirements that are too burdensome may hinder the acceptance of RUC and potentially decrease compliance.

Strategy 1: Consider the user experience when selecting a mileage reporting method.

Mileage reporting provides the most direct contact between the RUC payer and the RUC system, so it constitutes a significant portion of the RUC payer’s user experience. A good user experience with a technology is vital for success. When the user experience is not polished, users may oppose or choose not to participate in RUC programs. To improve the user experience, online interfaces should be smooth, and setting up a RUC technology should take as few steps as possible.

- Phase: Setup

- Activity: System Design (State and Vendor)

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Strategy 2: Set up customer service centers and train staff so that live customer service can be offered from Day One of a RUC program.

Specify customer service infrastructure requirements—including phone, any interactive voice recognition, and email systems—and all needed redundancies to ensure customer services operate, even in failure conditions.

- Phases: Setup; Ongoing Operations

- Activities: System Design (State and Vendor); System Implementation and Testing (State and Vendor); Live Operations

- Refer to the following building blocks:

Strategy 3: Establish customer service standard operating procedures, including how to answer a phone call, how to direct calls, how to deal with upset customers, and other related items.

Base these procedures on the state’s and vendor’s customer service best practices.