3.0 Current Practice

- 3.1 Environmental Review Context

- 3.2 Federal Policy and Guidance

- 3.3 State Environmental Procedures

- 3.4 Overview of Recent Practice

3.1 Environmental Review Context

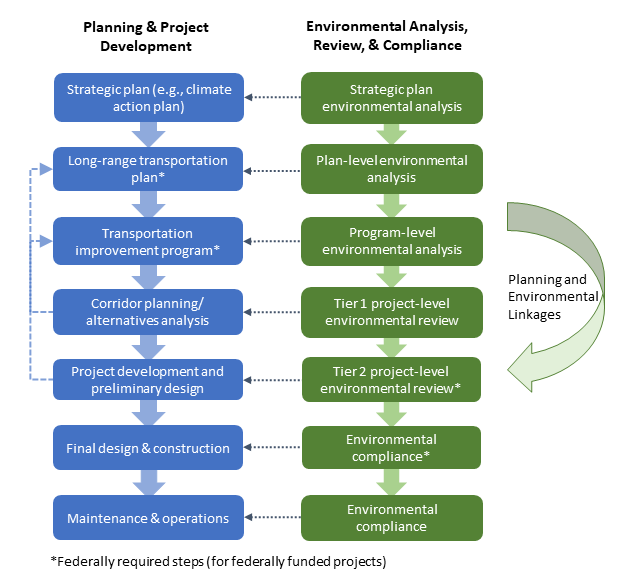

The process of planning, selecting, designing, and implementing transportation projects typically has multiple steps. Some are prescribed in accordance with federal regulations and guidance, while others may be undertaken at an agency’s discretion. Figure 3‑1 provides a schematic of the transportation planning and project development process, along with associated environmental review that may take place at each stage.

Some elements are required. For example, federal regulations require the development of a statewide long-range plan that sets overall policy and strategic direction for the transportation system, as well as a State Transportation Improvement Program that lists all projects that will be funded over a timeframe of at least four years. Pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), environmental review is also required for actions (specific projects) that are federally funded, need federal approval, or use federal property. NEPA review is typically done during the project development process to support a Record of Decision (ROD), Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI), or Categorical Exclusion (CE or CatEx) and approval for the project before it proceeds to final design and construction. A tiered environmental process may also be conducted to better define the scale and scope of the final project. Environmental information developed earlier in planning may also inform the final environmental documentation through Planning and Environmental Linkages. Some states also require environmental review pursuant to state-specific requirements that extend beyond NEPA. Other elements of this process may vary in their application. Figure 3-1 illustrates the phases of planning and project development and their relations to environmental review. For example, a state department of transportation (DOT) may conduct planning and implementation activities ranging from strategic and long-range planning to programming, corridor planning, project development, and construction, maintenance, and operations. Each stage of planning may be informed by corresponding environmental analysis, review, and compliance activities. Statewide planning and programming must be coordinated with metropolitan planning and programming conducted by Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) and may make use of environmental information from those activities.

3.2.1 NEPA and Council on Environmental Quality Guidance

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), signed into law in 1970, established a national policy requiring the environmental review of major federal actions in the United States. Generally triggered when an action requires federal approval, federal funding, and/or federal property, NEPA calls for federal agencies to take a “hard look” at the environmental consequences of their proposed actions before implementing the action. The National Environmental Policy Act also established the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) to oversee NEPA implementation, conduct research on environmental trends, and provide guidance based on findings.

The key aspects of NEPA review include:

- A clear “Purpose and Need” statement for the proposed action.

- Consideration of alternatives (including the No-Action alternative).

- Assessment and disclosure of environmental effects.

- Mitigation of adverse effects.

- Agency coordination.

- Public involvement (public engagement).[1]

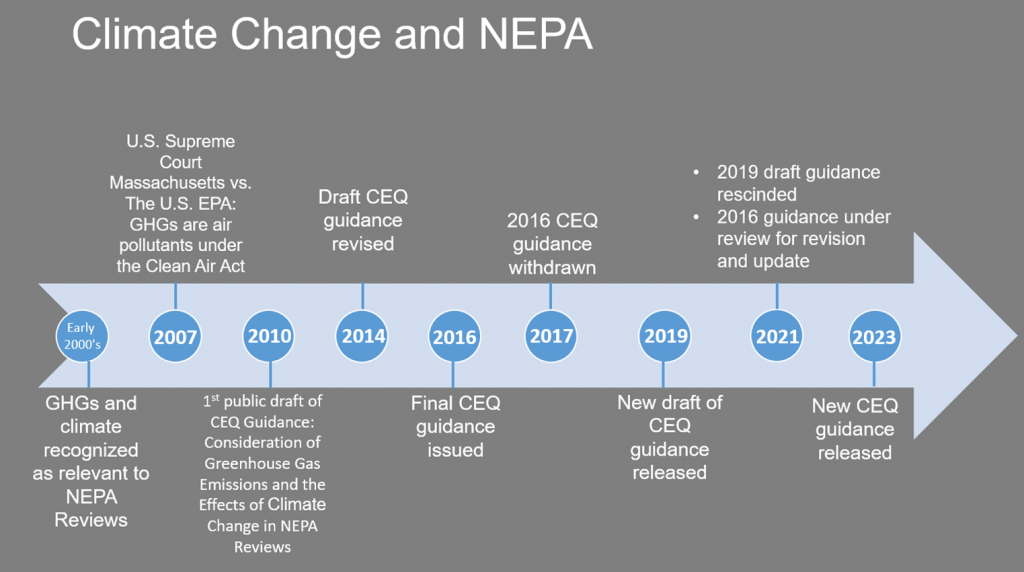

There are three “classes of action” or levels of NEPA review that determine the extent of documentation and public participation required based on the potential of the action to result in significant effects. CE or CatEx documentation is prepared for projects that are not likely to result in significant impacts on the environment based on an agency’s past experience with similar actions. An Environmental Assessment (EA) is prepared to evaluate the potential for significant impact for actions that cannot be categorically excluded. An Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) is prepared for actions that have the potential for significant impacts on the environment. As shown in Figure 3‑2, while the CEQ began drafting guidance for the consideration of GHGs (greenhouse gases) and climate change beginning in the late 1980s (CEQ 1989; CEQ 1997), a publicly available draft was not released until 2010 (CEQ 2010). With the 2010 draft, the CEQ solicited public comments on a number of questions, including whether CEQ should provide guidance to agencies on determining whether GHG emissions are “significant” for NEPA purposes, referring commenters to the Supreme Court decision in Massachusetts v. EPA. After public comments were received, a revised draft was released in 2014 (CEQ 2014). In 2016, the CEQ issued its Final Guidance for Federal Departments and Agencies on Consideration of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and the Effects of Climate Change in National Environmental Policy Act Reviews (CEQ 2016). The 2016 guidance was withdrawn in 2017 and a new Draft National Environmental Policy Act Guidance on Consideration of Greenhouse Gas Emissions was issued in 2019 (CEQ 2019). Pursuant to Executive Order (EO) 13990 of 2021 (EOP 2021a), Protecting Public Health and the Environment and Restoring Science to Tackle the Climate Crisis, the CEQ rescinded its 2019 draft guidance and began revising and updating the 2016 final guidance. As the outcome of this revision and update, the National Environmental Policy Act Guidance on Consideration of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Climate Change (CEQ 2023a) was published on January 9, 2023. This interim guidance was intended for agencies to use immediately while CEQ sought public comment on the guidance. The main aspects of the 2023 interim guidance are summarized in Sidebar 3-1.

Major revisions to NEPA implementation that took effect in 2020 were also withdrawn in 2021, pursuant to EO 13990 and EO 14008. In April 2022, CEQ finalized a narrow set of changes to the 2020 NEPA regulations that generally restored key provisions that were in effect prior to 2020 (CEQ 2022). In July 2023, CEQ released a Phase 2 Notice of Proposed Rulemaking—the Bipartisan Permitting Reform Implementation Rule (CEQ 2023b). Among other updates, this proposed rulemaking would implement the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023’s amendments to NEPA, which included a number of changes to make NEPA review more efficient. The rulemaking would codify the interim Guidance on Consideration of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Climate Change (CEQ 2023a) issued in January 2023. The rulemaking also contains other provisions that could affect or relate to GHG and climate change effects analysis, such as various provisions to improve procedural efficiency and codification of longstanding principles such as the consideration of “reasonably foreseeable” environmental effects.

Sidebar 3-1: Key Elements of National Environmental Policy Act Guidance on Consideration of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Climate Change (CEQ 2023a)

Alternatives analysis

- Reasonable alternatives that minimize or avoid adverse effects should be assessed.

- Agencies should leverage early planning processes to integrate GHG emissions and climate change considerations into the identification of proposed actions, reasonable alternatives, and potential mitigation and resilience measures.

- Where relevant—such as for proposed actions that will generate substantial GHG emissions—agencies should identify the alternative with the lowest net GHG emissions or the greatest net climate benefits among the alternatives they assess.

- There is no requirement for the alternative with the least emissions or climate change effects to be selected.

Direct and indirect GHG emissions effects

- Recommends that agencies quantify a proposed action’s projected GHG emissions or reductions for the expected lifetime of the action, considering available data and GHG quantification tools.

- Where information regarding direct or indirect emissions is not available, agencies should make best efforts to develop a range of potential emissions.

- If an agency determines that it cannot provide even a reasonable range of potential GHG emissions, the agency should provide a qualitative analysis and its rationale for determining that a quantitative analysis is not possible.

- “As with any NEPA review, the rule of reason should guide the agency’s analysis and the level of effort can be proportionate to the scale of the net GHG effects … with actions resulting in very few or an overall reduction in GHG emissions generally requiring less detailed analysis than actions with large emissions.”

Cumulative effects

- Cumulative effects should be considered for the proposed action and its reasonable alternatives.

- Due to the nature of GHG emissions as related to climate change and the NEPA process, the consideration of direct and indirect emissions is inherently a cumulative effects analysis.

Short-term and long-term effects

- Reasonably foreseeable beneficial and adverse effects, long and short-term, should be considered and explained as compared to the no-action alternative.

- The effects analysis should cover the action’s reasonably foreseeable lifetime, including anticipated GHG emissions associated with construction, operations, and decommissioning.

Disclosing and providing context

- In most circumstances, once agencies have quantified GHG emissions, they should apply the best available estimates of the social cost of carbon to support consideration in familiar values.

- Where helpful to provide context, such as for proposed actions with relatively large GHG emissions or reductions or that will expand or perpetuate reliance on GHG-emitting energy sources, agencies should explain how the proposed action and alternatives would help meet or detract from achieving relevant climate action goals and commitments.

- Agencies also can provide accessible comparisons or equivalents to help the public and decision makers understand GHG emissions in more familiar terms.

Consideration of the effects of climate change

- The agency should describe the affected environment for the proposed action based on the best available climate change reports.

- Impact analysis should focus on aspects of the human environment affected by the proposed action and by climate change.

- Available assessments and scenarios should be used; it is not necessary for agencies to conduct new research or analysis of potential impacts of climate change on the project area.

- When scoping for the climate change issues associated with the proposed action and alternatives, the nature, location, timeframe, and type of the proposed action and the extent of its effects will help determine the degree to which to consider climate projections.

Mitigation

- Agencies must consider reasonable mitigation measures, if not already included in the proposed action or alternatives, consistent with the level of NEPA review and the purpose and need for the proposed action.

- Given the urgency of the climate crisis, CEQ encourages agencies to mitigate GHG emissions to the greatest extent possible.

- Agencies should consider environmental design features, alternatives, and mitigation measures to address the effects of climate change on the proposed action.

- Mitigation efforts should be monitored.

Environmental Justice

- Agencies should consider whether the effects of climate change in association with the effects of the proposed action may result in disproportionately high and adverse effects on communities with environmental justice concerns.

- Agencies should meaningfully engage with affected communities regarding their proposed actions and consider the effects of climate change on vulnerable communities in designing the action or selection of alternatives.

Programmatic or broad-based studies and NEPA review

- Integrating the NEPA process throughout all stages of planning is encouraged.

- An agency may decide to provide an aggregate analysis of GHG emissions or climate change effects in a programmatic analysis and then incorporate it by reference into future NEPA reviews.

Applicability to existing processes

- Agencies should use this guidance to inform the NEPA review of all newly proposed actions. Agencies should exercise judgment when considering whether to apply this guidance to the extent practicable to an ongoing NEPA process.

3.2.2 U.S. DOT Resources

The U.S. DOT and its modal administrations have released various resources to implement CEQ guidance and facilitate the consideration of GHGs and climate change in environmental review. The main subjects and recommendations provided in these resources are summarized in Table 3‑1. The documents have included a Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) webinar presentation directly addressing the 2016 CEQ guidance, as well as FHWA documents on addressing resilience and vulnerability assessments, a Federal Transit Administration (FTA) programmatic assessment of GHG emissions associated with transit projects, and a U.S. DOT climate action plan.

Table 3-1. U.S. DOT Resource Documents Related to GHG Emissions and Climate Change Effects

| Short Reference | Title and Link | Contents | Additional Notes and Resources |

| FHWA (2016b) | FHWA Implementation of CEQ Guidance on Consideration of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and the Effects of Climate Change in NEPA (webinar presentation) | Summarizes 2016 CEQ guidance and discussion of implementation measures for transportation projects. Recommends a planning-level analysis approach to GHG emissions (in alignment with CEQ guidance’s provision for programmatic analysis), or a project-level analysis if planning-level isn’t available. Planning-level analysis may include regional or statewide long-range transportation plans, major investment studies, and Tier 1 environmental documents for large-scale projects. For the consideration of climate impacts on a proposed project, FHWA recommends considering potential mitigation measures and design options that increase resiliency. | Recommends utilizing relevant regional impacts or adaptation studies; statewide or metropolitan long-range transportation plans; major investment studies; environmental documents for large-scale projects. |

| FHWA (2017a) | Synthesis of Approaches for Addressing Resilience in Project Development | Provides guidance for integrating climate considerations into the transportation project development process for a range of projects. The document recommends considering climate change effects and adaptation early in the project development process (planning, scoping, and preliminary design/engineering). It describes key elements of an adaptation study and notes that the level of detail should be scaled to the project at hand. | Provides links to various FHWA-funded resources, including case studies and engineering manuals, as well as state and local regulations and guidelines. |

| FHWA (2017b) | Vulnerability Assessment and Adaptation Framework | Discusses the vulnerability of transportation infrastructure to extreme weather and climate change and provides recommendations for the integration of climate adaptation considerations into transportation decision-making. The report includes examples of vulnerability assessments conducted nationwide and provides a structured step-by-step process for conducting vulnerability assessments. | Examples of vulnerability assessments include five FHWA climate change resilience pilot projects, as well as various related studies conducted by FHWA and other transportation agencies. |

| FTA (2017) | Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Transit Projects: Programmatic Assessment | Reports on whether certain types of proposed transit projects merit detailed analysis of their GHG emissions at the project level. The report includes a GHG emissions “typology matrix” – a lookup table to estimate partial lifecycle emissions for the construction, operations, and maintenance phases of sample projects by project type (e.g., bus, rapid transit, light rail). The tool accounts for the GHG benefits of personal vehicle emissions displaced as a result of ridership increases with transit projects. The programmatic assessment has been incorporated by reference and used as a tool in NEPA reviews for specific transit projects. | Provides an optional source of data to reference in future environmental documents for specific projects. |

| U.S. DOT (2021a) | Climate Action Plan: Revitalizing Efforts to Bolster Adaptation and Increase Resilience | Issued to ensure that the DOT and plans/policies for federally supported transportation infrastructure consider climate change effects and incorporate adaptation and resilience solutions whenever possible. | Contains guidance from the U.S. DOT on how it will seek to incorporate climate change considerations and mitigate GHG emissions into its various agency activities, including planning and project reviews. |

3.2.3 Policy and Guidance Related to Equity and Environmental Justice

In 1970, the U.S. DOT issued implementing regulations of Title VI, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, or national origin [49 CFR §21.5(a)]. U.S. DOT policy calls for efforts to prevent a disproportionate distribution of burdens and, consistent with Title VI, a “denial of, reduction in, or significant delay in the receipt of benefits.” While this policy requires, at a minimum, an analysis to determine whether benefits and burdens are proportionately distributed, current practice is not to mandate proportionate outcomes. In contrast to Title VI, which prohibits certain activities, NEPA does not mandate particular results. In other words, NEPA defines procedures that must be followed before making a decision, but it does not restrict the decisions that can be made once the required procedures have been completed.

EO 12898, Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations, articulated environmental justice (EJ) as a national policy goal in 1994. The order requires federal agencies to identify and address the disproportionately high adverse human health and environmental effects of their programs, policies, and activities on low-income and minority populations. The EJ order has resulted in extensive implementing guidance issued by CEQ, U.S. DOT, and others that affect transportation planning. While EO 12898 and Title VI have distinct requirements, transportation agencies often conduct regional equity analyses that address Title VI, EJ, and other non-discrimination regulations (Twaddell and Zgoda 2020). EO 12898 is distinct from Title VI in its specification of equity for low-income and minority populations, although there is some overlap between the requirements. Other views on equity are possible considering different population group definitions; for example, EO 13166, issued in 2000, is focused on improving access to services for persons with limited English proficiency.

In alignment with EO 12898, both the U.S. DOT and CEQ released EJ guidance, Environmental Justice Guidance Under the National Environmental Policy Act, in 1997. This guidance was developed to assist federal agencies with EJ analysis during environmental review. U.S. DOT Order 5610.2(a) describes the process for incorporating EJ principles outlined in EO 12898 into all U.S. DOT programs, policies and activities. The order has subsequently been updated in 2012, 2020, and 2021. The most recent version, Order 5610.2(c) (U.S. DOT 2021b), states “For the purpose of DOT’s Environmental Justice Strategy, fair treatment means that no population, due to policy or economic disempowerment, is forced to bear a disproportionate burden of the negative human health and environmental impacts, including social and economic effects, resulting from transportation decisions, programs and policies made, implemented and enforced at the Federal, State, local or tribal level.” The 2021 Order calls for the U.S. DOT to evaluate the environmental effects of its activities, propose measures to mitigate disproportionately severe environmental effects and to provide offsetting benefits for communities, consider alternatives that could avoid disproportionately severe environmental effects, and solicit and consider public input (U.S. DOT 2021b). The 2021 update also defines the term ‘minority’ and ‘low income’ for DOT’s EJ analysis: ‘minority’ is defined as a person who is Black, Hispanic or Latino, Asian American, American Indian or Alaskan Native, or Native American or other Pacific Islander; ‘low income’ is defined as a person whose household income is at or below U. S. Department of Health and Human Services Poverty Guidelines. EO14096, Revitalizing Our Nation’s Commitment to Environmental Justice for All, signed in April 2023, further charges each federal agency with making achieving EJ part of its mission consistent with statutory authority, requiring each agency to submit to the Chair of CEQ and make publicly available an Environmental Strategic Plan setting forth the agency’s goals and plans for advancing EJ, and establishing a White House Office of Environmental Justice within CEQ.

In response to EO 13990 and 14008, Phase 1 of the CEQ’s rulemaking asserted agencies’ authority to develop agency-specific NEPA procedures that align with their own mission and circumstance including the possibility to require public hearings or provide more special consideration for EJ considerations. The proposed Phase 2 rulemaking would take further steps to ensure consideration of EJ populations under NEPA.

Modal administrations under the U.S. DOT have issued their own implementing orders and guidance on EJ as well. FHWA Order 6640.23A provides direction for determining whether low-income and minority populations are present and for determining whether those populations would experience disproportionately high and adverse impacts as a result of a project.

The FHWA Environmental Justice Reference Guide (FHWA 2015a) is intended to help transportation agency staff with ensuring compliance with EJ requirements in all stages of planning, development, and implementation for FHWA projects, programs, and policies. It includes sources of demographic, transportation, and environmental data; methods for analysis; planning considerations; public involvement strategies; and methods for addressing EJ through various project stages. The guide also includes requirements and recommendations for consulting with Tribal Governments.

Commonly referred to as the FTA Circular, the FTA Environmental Justice Policy Guidance for Federal Transit Administration Recipients was released in 2012. It provides detailed procedures for conducting an EJ analysis, with specific guidance on NEPA. Key components of conducting EJ analysis described in the document include gathering community data and information, public engagement, evaluation of effects, alternative selection, and mitigation. It also discusses EJ principles and their specific application to transportation planning/projects and the written components of EJ in environmental reviews and suggests effective strategies for public engagement and for scoping and analyses.

In 2016, the Federal Interagency Working Group on Environmental Justice and NEPA Committee published a report on Promising Practices for EJ Methodologies in NEPA Reviews (EJIWG 2016). The report outlines actions that agencies can take to meaningfully engage affected communities as part of NEPA review. It also outlines steps for considering EJ under NEPA, including defining the affected environment; identifying potentially affected minority and low-income populations and assessing potential impacts; assessing potential alternatives; determining whether potential impacts to minority populations and low-income populations are disproportionately high and adverse; and developing mitigation and monitoring measures. The report suggests that agencies could consider how impacts from the proposed action could potentially amplify (or mitigate) climate change-related hazards in minority and low-income populations in the affected environment.

Numerous NEPA reviews, including transportation project EIS documents, have considered the potential for the project to have a disproportionate adverse impact on EJ communities. Impacts most commonly addressed include socioeconomic conditions, air quality, noise, and hazardous materials. To date, the assessments of EJ and disproportionate impacts of projects conducted under NEPA have generally not included a discussion of climate change or its disproportionate burdens. Similarly, discussions of climate change under NEPA have generally not included consideration of equity or climate justice. That trend may soon be changing under Executive Orders 13990 and 14008, issued in 2021, and the Justice40 Initiative (see Sidebar 3-2).

Sidebar 3-2: Justice40

The Justice40 initiative is an effort to ensure that federal agencies work with states and local communities to deliver at least 40 percent of the overall benefits from federal investments in climate and clean energy to disadvantaged communities. Interim guidance issued for the Justice40 initiative provides initial recommendations to achieve the Executive Order 14008 goal (EOP 2021b). The memo provides definitions and examples of key EJ concepts and terminology, summarizes reporting requirements, and lists pilot programs to maximize benefits to EJ communities. Of relevance to this guide, the consideration of whether a community is disadvantaged should include “high transportation cost burden and/or low transportation access.” Moreover, covered programs include “climate change” and “clean transportation,” as well as associated training and workforce development. The memo provides examples of benefits, including benefits under climate change and clean transportation categories. The memo identifies pilot projects for specific agencies, including two pilots for the U.S. DOT—the Bus and Bus Facilities Infrastructure Investment Program and the Low or No Emissions Vehicle Program. The Justice40 interim guidance memorandum mentions NEPA in the context of outreach.

Prior to the release of the interim CEQ guidance in January 2023, there was no federal requirement to consider and analyze GHG emissions or climate change effects in a transportation project environmental review. Those states that were already addressing these issues were doing so for a variety of reasons, including state or agency directives or policies requiring their consideration; in response to state legislation addressing climate change, either through Climate Action Plans or specified emission reduction targets; in direct response to public and stakeholder interest; in response to the 2016 CEQ guidance that was issued and then rescinded (CEQ 2016); and/or anticipating future CEQ guidance. The degree to which climate change issues have been addressed by the states varies quite widely and is continuing to evolve following release of the latest interim CEQ guidance.

Some of the first environmental review documents to include substantive consideration of climate change were prepared pursuant to state environmental laws, even prior to the first draft federal guidance in 2010 (CEQ 2010). By 2003, New York State had developed unpublished draft guidance to include GHGs in its Environmental Procedures Manual, which was used to prepare analyses for environmental review documentation. In 2007, Massachusetts finalized its Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act (MEPA) Greenhouse Gas Emissions Policy and Protocol. The 2007 settlement of the California vs. San Bernardino County challenge to the county’s General Plan on the grounds that it did not adequately consider climate change required the county to, among other initiatives, prepare a Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction Plan and conduct environmental review pursuant to the California Environmental Quality Act. By 2009, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) had published draft guidance on the analysis of GHG emissions for certain projects with DEC as the lead agency (New York State DEC 2009). Other states have developed their own guidance subsequent to the publication of the first draft CEQ guidance in 2010. Table 3‑2 summarizes requirements and guidance for GHG analysis in 11 states with specific written guidance on the circumstances under which GHG analysis is required in transportation project environmental reviews required under federal and/or state law.

Table 3-2. Published State-Level Requirements and Guidance for GHG Analysis in Transportation Projects

| State | Requirements | Reference |

| California | GHG emissions from projects are documented in an air quality report for projects for which an EIS or air quality conformity compliance is required. Quantitative analysis is to be done for congestion relief and other roadway capacity-increasing projects. Emissions to be quantified include construction emissions, and operational emissions for the existing year, opening year and 20-year design year. For other project types that will likely result in minimal or no increase in operational GHG emissions, a qualitative discussion should be included about the operation of the project and the low- to no-potential for an increase in GHG emissions. | Caltrans (2020a) |

| District of Columbia | A qualitative discussion of the GHG emissions associated with the project is to be included in the air quality analysis. | District of Columbia DOT (2012) |

| Colorado | Transportation operating and construction GHG emissions should be quantified for EAs, EISs, and other Regionally Significant/Transportation Capacity projects in the state’s 10-Year Plan. Additional guidance is provided related to the consideration and documentation of mitigation measures, including mitigation actions undertaken to support other plans and policies. | Colorado DOT (2023) |

| Massachusetts | Projects that require an Environmental Impact Report under MEPA must quantify emissions and reduce GHG emissions to the maximum extent feasible. Assumptions, methodology, and inputs are determined by individual agencies to best quantify the GHG emissions from the project. All projects on transportation improvement programs in Massachusetts are subject to a GHG assessment. The MPO must determine the direction of the GHG impact and its cause. Most of the projects require quantitative determination using Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ) Improvement Program spreadsheets, a reporting template, and a spreadsheet of emission factors provided by the Massachusetts DOT. | Massachusetts EOEA (2010, 2021);Massachusetts DOT (2020) |

| Minnesota | A quantitative analysis is required for construction and maintenance emissions for all projects and operational emissions for projects that affect volumes and speeds. Some exceptions apply, such as when the total construction cost is less than $1,000,000 or the project is not a project type included in the Minnesota Infrastructure Carbon Estimator tool. | Minnesota DOT (2020a) |

| Oregon | Project-level GHG analyses are typically conducted for EISs and some EAs. Operational, construction, and maintenance emissions are reported as cumulative changes over the life of the project. | Oregon DOT (2018a) |

| Pennsylvania | Projects that meet the definition of “regionally significant” under the federal transportation conformity regulation require a qualitative or quantitative GHG analysis. If the project affects vehicle-miles traveled or speeds and has not been assessed under a planning-level GHG assessment, then a quantitative analysis is performed; otherwise, a qualitative analysis is performed. Operational, fuel-cycle and construction emissions are reported. | Pennsylvania DOT (2017) |

| Virginia | Virginia DOT developed draft guidance that is intended to be included in the agency’s Project-Level Air Quality Analysis Resource Document. Draft guidance specifies conditions for which a project-specific quantitative analysis, reference to a statewide analysis, qualitative assessment, or no assessment is required. | Virginia DOT (2022a) |

| Tennessee | A qualitative discussion of the GHG emissions associated with the project is to be included in the air quality analysis for EIS projects. | Tennessee DOT (2011) |

| Texas | The Texas DOT has prepared an inventory of statewide transportation GHG emissions and identified strategies to reduce GHG emissions from the transportation sector. For a project, the agency may refer to this statewide analysis or conduct a project-specific GHG analysis. | Texas DOT (2020);Texas DOT (2021) |

| Washington | Typically, EIS and EA projects require a quantitative analysis, while CEs require no analysis or a brief qualitative discussion. Quantitative analysis may include a quantitative planning-level GHG analysis, which is referenced in the project environmental document. Operational (including tailpipe and upstream), construction, and maintenance emissions are reported. Template text is provided. | Washington State DOT (2018);Washington State DOT (2020) |

For project-level emissions analysis, the state guidance generally considers environmental classification or project type. For those states that use environmental classification as a criterion:

- CEs usually will not have a project-level greenhouse gas analysis.

- EISs usually will have a project-level greenhouse gas analysis.

- EAs may or may not have a project-level greenhouse gas analysis, depending on the state’s guidance.

For those states that use project type as a criterion, projects requiring GHG analysis are typically those that will result in operational change(s) on the facility, such as changes in geometry, volume, speed, delay/congestion, vehicle types, or other parameters that could change the amount of emissions generated by vehicles using the facility.

Some states have established cases in which a statewide GHG emissions analysis may be referenced in lieu of performing a project-specific quantitative analysis. Other states discuss emissions qualitatively. The qualitative discussions typically describe sources of emissions and defer to statewide, national, or global solutions. The quantitative emissions analyses typically report emissions from one or more build alternatives as well as the no-build alternative. Quantitative analyses typically include emissions associated with the construction of the project as well as changes in emissions related to changes in travel and vehicle activity resulting from the project.

A few states, including California, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia, and Washington State, have specific project-level written guidance for addressing climate change effects in project-level environmental reviews. Template language may be provided to assist in delineating the effects of climate change upon the project and the project area. However, many other states provide adaptation or climate change effects guidance through statewide or planning-level studies and documents. Typically, this guidance references a statewide, state-region, or state-climatic zone vulnerability assessment (often performed by academic institutions or other outside agencies). The guidance focuses on climate change effects most likely to affect the state (e.g., sea level rise in coastal states). Some vulnerability assessments are qualitative in nature, while some are very detailed in describing and quantifying expected climate change effects.

According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency database of Environmental Impact Statements, a total of 89 NEPA Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) documents for projects or programs where a transportation agency was the lead agency were issued (with a notice published in the Federal Register) from January 2016 to December 2021. Based on a review of these documents, consideration of GHG emissions in environmental review, including quantitative assessment, appears to be increasing. Consideration of climate change effects also appears to be increasing and becoming more robust, considering a broader range of stressors. To date, there have been few or no instances of linking GHG emissions, climate change, and equity issues in environmental documentation. There continues to be a very wide range of approaches to considering GHG emissions and climate change in NEPA reviews.

3.4.1 GHG Emissions

Addressing GHG emissions. A review of the 89 FEIS documents found that 56 (approximately 63 percent) substantively addressed GHG emissions—either quantitatively, qualitatively, or by incorporation of prior studies, agency—or statewide efforts, and/or discussion of ways to reduce emissions. Of the remaining 33 documents, 14 did not include any discussion of GHG emissions. However, 6 of those 14 were Tier 1 or corridor-level study documents that in many cases deferred further analyses to Tier 2 studies. The 19 FEIS documents that acknowledged but did not substantively address GHG emissions very generally (without project specifics) discussed GHG emissions and mitigation or included statements about the lack of available guidance, the impracticality of addressing climate change at the project level, the insignificance of likely project emissions as compared to emissions at a state, national, or global scale, or the lack of significance thresholds; or made brief concluding statements about project benefits to emission reductions or sustainability.

Indicators of impact. Projects that qualitatively addressed emissions generally included statements about GHG emission sources and information on whether the project would increase or decrease GHG emissions, along with any noteworthy differences in expected GHG emissions with different alternatives. Some projects used the projected increase or reduction in vehicle-miles traveled (VMT) as a proxy for comparing operational GHG emissions, thereby striking a middle ground between not quantifying GHG emissions at all and doing an analysis using emission models. The FEIS documents for several projects noted the benefits of addressing GHG emissions at the agency or state level, rather than on a project-by-project basis and referenced state or agency initiatives to reduce emissions from transportation.

Analysis details. A more in-depth review of 21 FEIS documents was conducted to examine specific methods for evaluating GHG emissions. The review included 16 projects considered “highway projects,” four projects considered “transit and rail” projects, and two pipeline projects. The following observations were made:

- Of these documents, 13 included quantitative GHG analysis, seven included qualitative GHG analysis, and one included no GHG emissions analysis.

- Operating emissions were quantified for 12 projects; construction, maintenance, and/or facility operations emissions for eight projects; and upstream or life-cycle emissions for one project.

- Emissions analyses typically compare “build” scenarios with “no-build” scenarios and consider both “horizon years” and base years for the analysis. Of the documents quantifying emissions, six compared a single “build” or locally preferred alternative to the same future year “no-build” condition; four reported emissions for multiple alternatives; two included comparisons with current or base year emissions; and one project reported emissions in more than one future year.

- The geographic scope ranged from emissions on the project network links only, to a “buffer area” of a certain distance to the regional level.

- The majority of projects (four out of seven) reported annual CO2 reductions between 35,000 and 75,000 metric tons (MT) CO2e. Two of the seven projects reported annual CO2 reductions of less than 10,000 MT CO2e, while one project (Atlanta Regional Managed Lane System Plan) reported a potential CO2 reduction of over 3,000,000 MT CO2 in the horizon year. Construction emissions were primarily reported as a single “lump sum,” ranging anywhere from 18,000 MT CO2e to around 100,000 MT CO2e (over 250,000 MT for one pipeline project).

- For projects that estimated on-road mobile source emissions, VMT changes were typically calculated using a regional travel demand model. In some cases, emissions were then calculated using the Environmental Protection Agency Motor Vehicle Emission Simulator software; in other cases, changes in VMT were multiplied by emission factors obtained from other sources.

For more details on these 21 EIS documents, see “Appendix C: Review of EIS Documents.”

Mitigation measures. Many FEIS documents that did not quantify GHG emissions discussed mitigation options, whereas conversely, many FEIS documents that quantified GHG emissions did not discuss mitigation. Some documents noted that no mitigation is required because the project would reduce emissions, because emissions would be small, or because there is no significance threshold. (Based on NEPA’s 40 most asked questions, FHWA notes that “the mitigation of impacts must be considered whether or not the impacts are significant.”)

Numerous documents did discuss efforts to reduce emissions, including projects that did not quantify emissions and projects that disclosed potential GHG reductions due to project operations. Some mitigation measures identified were agency or state-level initiatives or policies that would generally be applicable or implemented at the project level. For example, the FEIS for the Northwest State Route 138 Corridor Improvement Project in Los Angeles County, CA, discusses California’s goals to reduce GHG emissions and the expectation that GHG emission reductions would result from cleaner vehicle technologies, lower‐carbon fuels, and reduction of VMT (Caltrans 2017b). The FEIS also references GHG emission reduction strategies and performance targets included in the California Transportation Plan, such as increasing the percentage of non‐auto mode share, reducing VMT per capita, and reducing agency (Caltrans) operational emissions. The FEIS notes that Caltrans administers funding for technical assistance programs that have GHG reduction benefits, including the Bicycle Transportation Program, Safe Routes to School, Transportation Enhancement Funds, and Transit Planning Grants. Some of the FEIS documents reviewed identified options to reduce emissions at the project level. Generally, no commitments regarding measures to reduce emissions were made in the FEIS documents reviewed.

Drawing conclusions. Based on the review of the FEIS documents, as well as prior studies by others (Woolsey 2012; Wentz 2016; Siegel 2019; Saloni 2017), the most challenging aspect of including climate change under NEPA is drawing a conclusion. This challenge may stem from agencies and NEPA practitioners being accustomed to having a numeric significance threshold, such as the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) and transportation conformity thresholds that exist for criteria pollutants. A meaningful threshold for GHG emissions may not be possible to establish, and some states and local governments have shifted away from discussion of the significance of project-level GHG emissions to approaches that consider the project’s overall consistency with agency, state/local, or global goals to reduce emissions. Nevertheless, the review of FEIS documents indicates there are currently several common approaches to concluding the NEPA discussions of GHG emissions, as summarized below.

- Conclude that, as compared with a no-action scenario, the project would reduce GHG emissions.

- Conclude that, although GHG emissions would increase, the project would not result in a capacity increase, and the increase in emissions is therefore not attributable to the project, but rather to development and associated activity that would happen with or without the project.

- Conclude that the project would reduce GHG emissions by reducing congestion and improving speeds.

- For transit and high-speed rail projects, conclude that the project would reduce VMT or aviation emissions via modal shifts and that project construction emissions would be temporary and negligible.

- Conclude the increased emissions (from operation and/or construction) are very small in comparison to the overall emissions or transportation sector emissions at a larger scale (statewide, nationwide, global, etc.). Note that CEQ guidance advises against comparing project emissions with global emissions (CEQ 2023a).

- Conclude that, although the project would result in an increase in GHG emissions, agency or sector-level efforts to reduce emissions (e.g., fleetwide emission reductions) would eventually address the problem.

- Conclude that the project would reduce emissions or implement measures that would result in consistency with emission reduction or sustainability plans.

- Conclude that since there are no significance thresholds, no conclusions can be reached, or that the conclusions would be speculative.

3.4.2 Climate Change Effects

Of the 89 FEIS documents reviewed, 56 included no mention of potential climate change effects on the proposed project or action. Twenty-three FEIS documents included a substantive discussion by identifying vulnerabilities at the project level or incorporating regional, pilot, or agency studies by reference. Another ten FEIS documents acknowledged the potential effects of climate change, with some documents including a generic discussion of potential climate impacts at the state or agency level without connecting those impacts to the project. Some documents just briefly mentioned a project’s vulnerability or the need to protect critical systems, and some Tier 1 documents deferred additional assessment to Tier 2.

Although the number of FEIS documents is too small to draw firm conclusions regarding trends, it appears that more recent EIS documents are more likely to include a discussion of climate change impacts on the project and to identify adaptation and resilience measures. More recent NEPA documents, when including a discussion of climate change effects, tend to include a comprehensive review of climate stressors, while earlier documents were more likely to focus on sea level rise and flooding. Some documents noted the lack of design guidance for adaptation and resilience. Some documents noted that the project would implement state or agency guidance on improving resilience to the impacts of climate change. Generally, no commitments regarding resilience and design considerations were made in the documents reviewed.

While virtually all of the FEIS documents reviewed assessed the potential for disproportionate adverse impacts to EJ communities, only one of the assessments considered the potential for differential impacts of climate change, different vulnerabilities, or different adaptive capacities within those communities. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s assessment of EJ considerations under the Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards for Model Years 2024–2026 is described further in Section 5.4.2.

3.4.3 Identified Legal Challenges

According to the Climate Case Litigation Database (Sabin Center undated), as of early 2022, there were 1,356 legal cases in the United States that materially included climate change. Of that number, 308 cases were brought under NEPA and 226 cases were brought under state environmental review laws. With close to 40 percent of climate cases in the United States brought on the grounds of environmental review law, environmental review documentation is clearly vulnerable to litigation based on the argument that the documentation did not adequately consider the proposed action’s contribution to, or effects from, climate change. The challenge of meaningfully addressing climate change at the project level, the lack of detailed guidance, and the great variability of when and how climate change is addressed in environmental review from project to project and across the United States likely all contribute to this vulnerability.

By early 2022, there were 17 NEPA legal challenges to the FHWA on the basis of climate change or GHG emissions. Of those cases, nine were ruled in favor of the FHWA, two were ruled in favor of the plaintiff, two cases were dismissed (one with the stipulation that the project would incorporate various mitigation measures), and the remaining cases were pending.

3.4.4 Stakeholder Input

As part of the research to develop this guide, a workshop and interviews were conducted with nine non-governmental and community-based organizations representing environmental and equity community interests. The objectives of this outreach were to obtain a better understanding of (1) how communities have or have not been able to meaningfully participate in environmental review processes for major transportation projects and (2) ways that state DOTs could better engage communities regarding transportation projects and climate impacts.

The following challenges and suggestions emerged as common themes during the workshop and follow-up interviews:

- NEPA was not designed for community engagement but rather for evaluating options. Communities should be engaged both prior to and during NEPA using an “all of the above” approach. Meaningful engagement during planning and programming can help ensure that communities have input on whether a project that may affect them should even occur at all. When it comes to NEPA, the public is only engaged at the stage of alternatives analysis (i.e., typically once a project has gotten to 30 percent design and the Purpose and Need statement has already been developed). Ideally, there should also be mechanisms for community stakeholders to be involved in the earlier stages as well, articulating whether a project is needed rather than reacting to different project proposals.

- Community engagement would improve if community members had a better understanding of the stakes and legal implications of the process underway (including long-range planning, comprehensive planning, programming, project design, and others). This would help community members to find the best opportunity to engage.

- Planning does not always inform programming to the degree that it might. Community members expressed frustration at the lack of clarity on how engagement would be used.

- NEPA practices differ significantly from agency to agency, and NEPA in practice is often very different from how it appears as written. Many projects proceed under CEs despite real-world impacts. In some cases, the intent of the law does not appear to be fulfilled by agencies’ execution of the law.

- Agency staff is often under-resourced and/or lacks the experience or knowledge to do community engagement effectively. One approach that can be effective is for agencies to contract or partner with local organizations to carry out community engagement.

- There is a need for more robust data and definitions around community impacts. For example, localized effects (e.g., to individual households) may be better indicators of harm than regional indicators.

- A lack of clarity on what amounts to “community impacts” or public harms can sometimes lead to beneficial projects that would reduce overall emissions not being implemented. Examples include transit-oriented development, affordable housing, and renewable energy projects.

- Traffic impacts are still often the most heavily weighted impact in NEPA analysis of “environmental impacts” and are used to justify project decisions that will increase emissions.

There is a lack of clarity on whether federal funds can be used towards some of the best practices that are essential for effective community engagement. For example, states and MPOs are not always clear on whether they can use federal funding to compensate community members for their time in engagement processes around planning or project development. The ability to compensate community representatives for their time would make it more feasible for EJ and equity-focus communities to be heard during the planning, project development, and environmental review processes, and in itself would be an important step in improving equity in public engagement.

[1] In the NEPA Implementing Regulations Revisions Phase 2 proposed in July 2023, CEQ proposed to update references to “public involvement” throughout the CEQ regulations to “public engagement.” CEQ proposed this change because the word “engagement” better reflects how federal agencies should be interacting with the public. According to CEQ, the word “engagement” reflects a process that is more interactive and collaborative compared to simply including or notifying the public of an action (CEQ 2023b).