Airport Impact Areas

Introduction

A communicable disease event in an airport can affect multiple interconnected areas—including staff wellness, financial stability, stakeholder coordination, operational continuity, and public communication—all of which are explored in this section to support comprehensive preparedness and response planning.

Staff Wellness

Customs and Border Protection Personal Protective Equipment and Social Distancing

To minimize exposure, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) enforced social distancing and personal protective equipment (PPE) requirements for all their officers and passengers during the COVID-19 pandemic. All employees who could not telework were given extensive PPE that included plexiglass shields at screening desks, N95 respirators, eye protection, and disposable outer garments, along with comprehensive guidelines on how to use the PPE properly. This level of PPE was distributed based on infectious disease risk, job function, and job setting. All the CBP facilities were also issued sanitary guidelines to further prevent the spread of communicable diseases and ensure that their workforce was safe and able to accomplish their mission. The U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) highly encouraged airports to separate passengers within the queuing space to adhere to social distancing practices while limiting the number of passengers allowed into the Federal Inspection Station.

Transportation Security Administration PPE and Social Distancing

The Transportation Security Administration’s (TSA) Transportation Security Officers (TSOs) are considered essential personnel and can interact with hundreds, even thousands of passengers daily. TSA worked with different airports to implement barrier shield installations and the creation of physical separation mechanisms (i.e., placing of metal search tables between passenger and Explosive Trace Detection tables).1 The USDOT recommends various practices to keep TSOs protected, including ensuring that all TSOs are wearing appropriate PPE such as masks and gloves; ensuring there is increased separation from passengers and enforcement of social distancing requirements; implementing screening procedures that limit physical contact with the passengers; and frequent routine cleaning of high-touch surfaces.2

Multiple airports implemented new screening procedures to avoid contact between TSOs and passengers. For example, some large airports implemented technology that minimizes physical contact during passenger travel document checks while providing enhanced fraudulent identity document detection capabilities, confirming the identity of travelers along with providing their flight information.3

Vaccination

Airports and airlines did their best to incentivize their employees to get vaccinated while also respecting employee’s medical privacy. One airline initially offered a combination of financial incentives, such as an additional day of paid time off from work and $100 in health rewards, as well as an employee lottery that gave over $1 million to vaccinated employees. Some airports became a state health department COVID-19 testing and vaccination site, supporting both airport and airline employees. Offering vaccination and testing resources in the non-secured areas of the airport allowed medical officers and their equipment to enter the airport without needing to process through TSA and saved time in badging procedures. Airports that had stricter vaccination requirements provided employees the option to forgo vaccination and instead undergo regular testing or pay a monthly health insurance surcharge.

Worker Incentives

Multiple airports and airlines had the opportunity to offer financial incentives to their employees for getting tested weekly. For example, one airline offered monetary incentives to their employees through their health and wellness benefits, provided one million free COVID-19 tests, and provided paid time away from work for employees exposed to COVID-19. Some airports offered their employees paid time off from work to get tested. For some airport employees that tested positive or exhibited symptoms, up to 80 hours of paid leave was provided. Once most employees were vaccinated, many airports reduced these benefits to 40 hours of paid leave.

Airport Finance

American Rescue Plan Act

In March 2021, the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) was passed. This law provided funds that were intended to support state governments to facilitate the ongoing recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. Funds were also made available to airports and airlines that had employees who performed essential work. One airport specifically mentioned that most of the funding they received from this program was funneled to PPE for their essential workers.

Budget Cuts

Most airports and airlines worked together to implement strict budget cuts in their facilities. One airport coordinated with its main airline sponsor to have some concourses completely closed. This helped reduce expenses, such as those associated with cleaning, utilities, and operations. Most airports determined that any non-essential activities would not be prioritized.

Capital Projects

Despite financial hardships, some airports took the opportunity presented by the low volume of passengers across the United States to perform capital improvement projects early in the pandemic. For example, one airport took advantage of the reduced passenger traffic to initiate and complete projects, such as building playrooms, nursery rooms, and stages for entertainment. Some smaller airports took advantage of this time to remodel their buildings, initiating projects like providing an upgraded lobby, expanding a passenger lounge, or adding a marketplace for concessions. One project also provided roadway improvements, additional exterior canopies, and upgraded office space for their airport authority. These helped enhance their customer services and provide better amenities for their employees.

Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act

In April 2020, the Federal Transit Administration announced $25 billion in funding from the CARES Act. Many airports used this funding to maintain their existing airport operations and compensate for the low passenger volume. Some were also able to use this funding to support their tenants by lowering their rental rates.

Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2021

In December 2020, the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSAA) of 2021 was signed into law. This law included $900 billion in supplemental appropriations for COVID-19 relief, of which $14 billion was allocated to support the transportation industry during the COVID-19 public health emergency. Some airports felt that the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) did not know how to administer CRRSAA grants and were unable to execute projects through the program.

Costs of Cleaning Products and Equipment

Due to the enhanced cleaning procedures required by the COVID-19 pandemic, more cleaning products and equipment had to be purchased. Supply chain shortages and increased demand led most companies to increase the prices of their cleaning products and equipment. Multiple airports used government grant money to purchase large amounts of cleaning products and equipment, including disinfecting fogging machines and disinfecting wipes. One airport mentioned that investing in cleaning technology, such as autonomous robots, helped them adjust to their reduced number of janitorial staff but was also their costliest expense. Maintaining and upgrading their HVAC systems and filters created additional costs as well.

Custodial Staff

Enhanced cleaning procedures led to an increased need for janitorial staff. Pay discrepancies sometimes disincentivized people from taking janitorial jobs, making it difficult for airports to hire enough staff to meet their needs. Some airports increased the wages of the janitorial staff by changing from a performance-based contract to a hybrid contract. Performance-based contracts required the airport to pay a monthly fee for another company to manage wages while a hybrid contract allowed the airport to manage the labor and benefits.

Family First Coronavirus Response Act

Many organizations across the aviation industry utilized the Family First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA) to provide additional paid sick leave and expanded family and medical leave to employees who were impacted by the COVID-19 virus. One airport specifically mentioned that most of their increased costs were spent on paying employees to work from home and relied on the FFCRA. Leave requirements for the FFCRA expired on December 31, 2020.

Government Grants

There were multiple grants offered by the federal government to aid airports during the pandemic. Per legal requirements, federally obligated airports must use airport revenue for the capital or operating costs of the airport. Funds from the CARES Act and other similar programs (i.e., CRRSAA, FFCRA, ARPA) were also required to be used for costs related to airport operations. During the COVID-19 pandemic the FAA determined that testing, health screening, and vaccinations were considered legitimate operating costs of an airport. Airport operating costs may also include the costs of enhanced cleaning of the terminal and other areas of airport property to minimize transmission of infectious diseases. These operating costs may include the purchase of incidentals and supplies, such as screening and testing equipment, masks (which can include cloth face covers), PPE, and products for cleaning, disinfection, and hand hygiene. Providing physical space to accommodate vaccinations administered through a third-party provider (e.g., a state or local health agency or other state-approved entity) can also be considered a legitimate operating cost like testing and health screening.4

Increased Costs

Financing the additional expenses brought on by the pandemic was also a challenge. Some of these expenses included buying new filters for air filtration, buying innovative technology used for cleaning and disinfection to help mitigate the spread of the virus, and obtaining PPE for personnel and customers. Retaining staff through financial incentives and paying employees to stay home if they were sick also impacted finances.

Loss of Revenue

One of the most discussed challenges airports and airlines faced throughout the COVID-19 pandemic was the loss of revenue due to reduced passenger volume. According to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), passenger volume declined significantly during the pandemic, causing as much as 60% of the world’s air fleet to be grounded due to decreased demand. ICAO noted that through 2020, just 1.8 billion passengers took flights compared to 4.5 billion in 2019.5 Airports’ long-term costs also increased due to new pandemic response measures that included enhancing ventilation systems, modifying airport facilities to accommodate social distancing, adding new signage, providing PPE, and increasing cleaning frequency. These mounting losses and increased operational costs could limit airports’ abilities to maintain full operations, potentially limiting air travel in certain locations. The loss of revenue also impacted airports’ ability to implement facility upgrades to enhance health and safety practices that mitigate the spread of COVID-19.

Many of the airports interviewed helped their tenants, such as airlines and concessionaires, with rent. Some regional airlines did not receive as much grant funding as larger airlines and had to temporarily or completely cease operations due to the lack of traffic during the COVID-19 pandemic. Starting in early February 2020, 59 airline companies suspended or limited flights to mainland China, and several countries, including the United States, Russia, Australia, and Italy, imposed government-issued travel restrictions. According to Airports Council International (ACI), it is estimated that the COVID-19 outbreak reduced global air traffic by 5.2 billion passengers for 2021 (the pre-COVID-19 forecast for 2021 was 9.8 billion passengers), representing a potential loss of 52.9%.6

Stakeholder Engagement

Airports Council International World Airport Health Accreditation

ACI accreditation assesses the airport’s health policies to ensure they are in line with the COVID-19 Business Recovery guidelines and the ICAO Council Aviation Recovery Task Force (CART) standards. The Airports Council International World (ACI World) Public Health and Safety Readiness (PHSR) Accreditation is a voluntary, industry-specific self-assessment that focuses on airport-specific operations. Those operations include airport cleaning and disinfection, physical distancing, signage, communication, and facilities based on ICAO CART topics. To apply, the airport completes a self-assessment, followed by an online ACI validation interview with key personnel. The ACI then awards accreditation for the next 12 months or makes recommendations for improvements needed to qualify for accreditation. Ongoing accreditation relies on continuous improvement and evidence-based self-assessment submissions. Currently, over 400 airports are accredited globally for the ACI World PHSR accreditation.7

Aviation Organizations

Aviation organizations such as the American Association of Airport Executives (AAAE), ACI World, and the ICAO can play a significant role in providing guidelines to airports and sharing information and best practices across stakeholders. Multiple airport authorities expressed their reliance on organizations such as ACI World for global communication and AAAE for communicating real-time updates on local exposure risks regarding the pandemic. Many smaller regional and general aviation airports had biweekly calls with external emergency management working groups to share best practices and lessons learned.

Federal, State, and Local Governments

Airports highlighted the importance of meeting with federal and state government authorities to better respond to the pandemic in a consistent and more unified manner. These efforts included meeting virtually with city leaders and officials, participating in city-wide communications, and attending sponsored Department of Homeland Security (DHS) calls. The discussions enabled information sharing about the spread of the virus and pandemic mitigation measures to help airports and local authorities better plan and prepare for the response. Airports should consider developing a team or identifying a point of contact that communicates regularly with government representatives to better anticipate public health incidents.

Communicating frequently with local, state, and federal government agencies, as well as public health and aviation organizations helps airports better understand and stay informed of the policies and procedures for a communicable disease response. During steady state operations or a communicable disease outbreak, having a working relationship with governmental, non-governmental, and medical entities will help the airport authorities ensure they are obtaining the most reliable information about local disease threats, modes of transmission, and mitigation best practices.

Airports that already had developed strong relationships with the FAA, CBP, and TSA mentioned that these relationships were instrumental in helping guide them during the initial phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although only a couple of airports had a Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) representative onsite to provide guidelines, staff from those airports that did have a CDC representative noted that sharing information about the benefits of such contacts during calls with the AAAE or ACI was helpful for other airports. Airports that already had developed relationships with their local fire department, local hospitals, and law enforcement felt they were in a better position to provide medical services and supplies to their customers, employees, and tenants.

Communicating with state and local health officials, as well as federal entities such as the CDC, is also important for airports during public health emergencies. Some airports dedicated a liaison employee to maintain communication with the local, state, and federal health agencies during the pandemic, while others brought in medical doctors and experts in epidemiology from local medical facilities to communicate risks and best practices to their staff. During a 2019 ACRP Insight Events Presentation,8 Dustin Jaynes, Public Health Administrator and Chief Epidemiologist at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport (DFW) explained how DFW used health education materials developed by the CDC to inform first responders about the Ebola virus disease transmission modes and how to recognize the preliminary symptoms of the disease. The airport also consulted with expert medical professionals, Doctors Without Borders, public health agencies, the WHO, and other organizations to provide informational materials to first responders.

Some airports stated that having daily touchpoints with medical facilities helped the airport leadership team understand how to protect themselves and help mitigate the spread of COVID-19 during pandemic operations. For example, one airport was able to make connections with an infectious disease doctor from a local university and utilized their expertise and advice to review many of their policies, protocols, and prevention plans in response to the pandemic. Multiple airports were able to partner with their local public health department to ensure information from different channels was being communicated accurately. Relationships with these entities should be built during both steady state and emergency operations.

Global Biorisk Advisory Council STAR Accreditation

The Global Biorisk Advisory Council (GBAC) is a division of the International Sanitary Supply Association, a worldwide cleaning industry association, which partnered with AAAE to deploy a program within U.S. airports.9 The overall program is not unique to the airport sector, but focuses on helping organizations and businesses prepare for, respond to, and recover from biological threats and biohazard situations. The GBAC STAR™ is the cleaning industry’s only outbreak prevention, response, and recovery accreditation for facilities. Currently, there are a total of 32 U.S. airports that have achieved the GBAC STAR accreditation and 40 airports that are in the process of obtaining the accreditation. GBAC STAR accreditation determines that a facility has established and is maintaining a cleaning, disinfection, and infectious disease prevention program to minimize risks associated with infectious agents like COVID-19. It also ensures the proper cleaning protocols, disinfection techniques, and work practices are in place to meet any biosafety challenges. Facilities prepare submission documentation in line with the GBAC handbook, the GBAC Council reviews the documentation for compliance, and, if successful, grants accreditation subject to annual review. AAAE and its members collaborated with the GBAC Scientific Advisory Board to develop a GBAC Airports Guidance Handbook that advises airport staff on best practices to combat biohazards and infectious disease.

Airport Operations

Infected Passengers

Airports had to develop protocols for the management of infected passengers. These protocols often included three primary elements: removal of the passenger from the plane using appropriate PPE, isolation of the passenger from employees and other passengers, and transportation of the passenger to a medical facility. Airports also helped coordinate the isolation and disinfection of aircraft and sometimes coordinated with the fire department to facilitate transportation of the infected person to a medical facility. Some airports noted that it was easier to determine the infection status for international passengers due to testing required when arriving in the country.

Staffing Shortages and Shift Management

According to the DHS, essential workers are those who conduct a range of operations and services that are typically required to maintain critical infrastructure operations,10 including airport operations. During the COVID-19 pandemic, multiple airports struggled to sustain operations with reduced staff. Reductions were in part due to staff getting sick and/or being exposed and needing to quarantine or isolate. To protect essential workers who were coming in daily, such as janitorial, maintenance, and security staff, some airports modified shifts and adjusted postings to accommodate social distancing requirements. Some revised their shift turnover procedures to be virtual (e.g., web meetings) so there would be no in-person overlap. While this helped keep staff safe, it created opportunities for communication failure regarding tasks and priorities for the incoming shift.

One airport mentioned that staffing shortages led them to declare an Operational Contingency Level event. The Operational Contingency Level was declared an ATC-zero—an FAA designation that a facility is unable to safely provide published air traffic services or traffic flow management in the case of the Air Traffic Control System Command Center.11 This led to the airport temporarily shutting down all operations and routing all incoming aircraft to different airport facilities.

Some airports cited the loss of trained operations staff with specific certifications (e.g., drivers with commercial driver’s licenses) and noted that it was a challenge to backfill these lost workers. It was also sometimes difficult to find people to hire for custodial services, in part due to pay discrepancies between custodial work and other jobs such as concessions. Airports must be prepared to manage staffing shortages and incorporate these expectations into emergency planning. Developing contingencies for working understaffed and outlining potential alternative work schedules for emergency operations should be incorporated into Communicable Disease Response Plans.

Transition to Telework

Teleworking is the practice of primarily working from home, making use of the internet, email, and the telephone. Many airport leadership teams struggled to implement and transition to telework. Making quick adjustments to identify who was essential and who was not proved to be time-consuming, and the need for support, guidelines, and tools for telework implementation also complicated the transition. Additionally, many workers supporting operations were not technology savvy and needed to be trained by the information technology (IT) department on how to use technology and software for telework.

The adaptation to telework resulted in an increased request for IT resources and increased costs for technology and administration to set up a robust capability to work from home. Multiple airports mentioned significant administrative work was needed early on. This included ensuring cybersecurity measures were set up correctly for all staff, implementing changes to software to enable remote access, and providing access to programs such as business management software. The IT departments and service desks spent additional hours beyond their regular shifts on the phone, instructing employees how to use the technology and providing them with access to servers and data as needed. Additionally, all training transitioned to virtual meetings, which made it less interactive and more difficult to fully engage staff. The transition also created a financial burden for airports to cover both the cost of recruiting and hiring more IT personnel, as well as the additional technology needed for those teleworking from home.

Incorporating collaborative technology (e.g., shared online spreadsheet tools, video conferencing) to empower airport teams to function in a remote environment was deemed important. Multiple airport employees used these programs concurrently for many functions including remote collaboration and easy information sharing.

Workforce Management and Operations

During emergencies, in addition to providing guidelines and communications, airport management must navigate major challenges regarding their workforce. During steady state operations, airports in the United States sustain hundreds, if not thousands, of jobs that include airport and airline employees, janitorial contractors, security contractors, maintenance and fuel workers, concessionaries, and more. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it became difficult to sustain regular operations due to staffing shortages, transitioning to telework, managing exposure and positive cases, and social distancing measures.

Communications

Daily and weekly updates between the airport staff and TSA were critical for sharing ideas, reporting progress, and comparing notes on passenger data. This communication and data sharing between airlines, airports, and TSA helped airport officials understand the volume of passengers, which helped inform data-driven decisions regarding staffing and cleaning protocols. Several airports, such as Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport, regulated the TSA checkpoint staffing based on the projections from the airlines each day.

Communicating with Airport Employees and Tenants

When communicating with airport tenants and employees during steady state operations, the airport’s role is to provide regular effective direction, education, and training to its employees and key stakeholders. Frequent communication allows airport staff to be aware of best practices, guidelines, and policies that ensure goals and expectations are clearly defined both before and during an emergency.

Regular communication with employees and tenants was critical for improving situational awareness. Some airports conducted daily standups with executives and stakeholders, and many airports continue to hold these conversations and recurring meetings. These communications gave them better insight into communicable disease threats around the country and world, as well as a better understanding of how their team is preparing for or responding to these threats.

Tenants and employees expect airport management staff to provide the most up-to-date information on communicable disease threats that impact their operations, as well as effective guidelines and policies for how to execute their work safely during a pandemic. This includes comparing all the guidelines and strategies provided by the different government entities such as the CDC, TSA, and federal, state, and local health officials and translating them into the airport’s continuous operations and protocols. Taking on the responsibility of evaluating these guidelines will ensure the employees and tenants know exactly what their role is and how to respond to a communicable disease threat at the airport facility, minimizing the effect on the operations. During the interviews conducted for this study, multiple airport officials described the topics discussed in their daily meetings conducted with key stakeholders, including updates on COVID-19 information, policy changes, best practices, data acquisition on positive cases, and different resources available to their tenants and employees.

Many of the airports interviewed had coordinating operations with their tenants under a single plan. Flight information was not always communicated effectively, resulting in misrepresentation of gating and flight information for passengers, which in turn led to delays and cancellations. Some of the airports interviewed noted that when airlines did not communicate flight data loads to TSA, this made it difficult to manage TSA checkpoints. Communication between airlines and TSA is important for the processing of passengers, as the correct allocation of TSA officers to each checkpoint depends on the load per day.

Communicating with External Parties

Airports must provide accurate and reliable information to their employees, tenants, and customers. For airports to stay up to date on policies, requirements, and best practices, they need to engage in regular communication with external parties, including aviation organizations, federal, state, and local governments, and public health and medical professionals. In some instances, there may be opportunities for partnerships with less traditional external partners. Airports also partnered with local universities to conduct pilot testing to determine the efficacy of different technologies for disinfecting surfaces.

By fostering relationships with government officials, public health organizations, academic organizations, and industry organizations, airports can build community partnerships. Some smaller airports interviewed mentioned not having pre-established relationships with government and medical authorities that could have helped them develop better guidelines and understanding of the virus. Relying on these entities for up-to-date information about local and international disease threats will help airports better prepare to respond to a communicable disease outbreak during both steady state and emergency operations. Airports should consider building regular relationships with these entities outside of emergency operations.

Communication Platforms

The best way to keep employees and tenants aware of their roles and responsibilities during a communicable disease threat is through a platform that disseminates information frequently, quickly, and effectively. Airports need a joint information center/system to provide unambiguous, dependable, and consistent messaging. A platform with portals that the employees and tenants can access at any time for the most up-to-date information about emergency situations could also provide guidelines and procedures for infected or exposed individuals. Other communication approaches include daily phone calls or virtual meetings, creating a website and a portal for employees, tenants, and the public, and utilizing signage, airport bulletins, and email chains with clear and concise verbiage to communicate guidelines, policies, and updates.

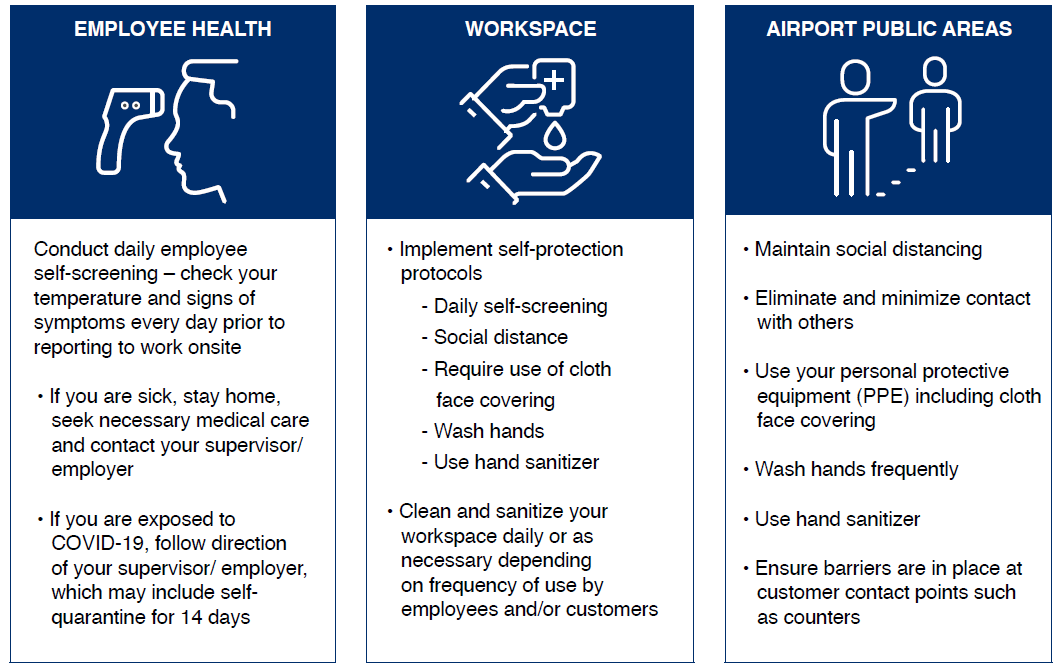

One airport employed an application that was open to travelers and employees and provided information on what is required at the airport. Other airports used manager forums, which were passed on to teams through an authority-wide email, with associated bulletins being shared with airport vendors. An airport commission used signage throughout the airport after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Figure 1 was taken from their COVID-19 preparedness plan, to remind their employees about personal hygiene, screening, and social distancing.

Source: Minneapolis and Saint Paul Metropolitan Airports Commission. (2021.) Travel Confidently Playbook.

Figure 1: Signage examples from Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport COVID-19 Preparedness Plan displaying common screening techniques displayed at airports.

Public Messaging

The airports’ communication with the public plays a significant role in how the public perceives the aviation industry’s response to communicable diseases, which contributes to the ability to sustain airport and airline operations. Several interviewees noted that travelers mentioned that a key source of their comfort was the fact that airports were communicating how they were managing the pandemic and what the customers could expect when traveling through the airport facility. Airports should communicate with the public by leveraging communication tools such as their website, signage, public announcements, and social media.

The public expects airports to provide reliable information on guidelines, policies, best practices, resources, travel advisories, and airport cleanliness procedures during a communicable disease event. Multiple airport and airline officials stated that gaining and keeping the trust of the customers during the COVID-19 pandemic was critical for the public to feel safe. One approach many airports implemented was the use of a publicly available website to provide updated information regarding the pandemic, using signage to inform customers on guidelines and procedures to keep themselves safe, informing the public when areas were closed off for sanitization, and implementing public health announcements at the airport facility.

Most interviewees indicated that their airports did not have a public messaging or communications plan in place for public health emergencies or pandemic/epidemic events prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Communications plans empower airport leadership teams to adapt normal communications processes during emergencies to provide critical information to potentially uninformed and anxious passengers. A study done by an airport emphasized the importance of ensuring that information regarding COVID-19 travel regulations was effectively messaged to the public and highlighted the fact that not only are passengers potentially uninformed of the latest guidelines and requirements, but some are part of a new generation of travelers that had never flown before and experienced travel for the first time during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The best way to keep the public informed is by utilizing multiple public messaging approaches and keeping them engaged and aware of what they can expect in the airport and during travel. Keeping the public engaged and informed will promote feelings of safety and security in the airport facility.

[1] Pesoke, David P. (2021). “20 Years After 9/11: The State of the Transportation Security Administration.” Accessed October 1, 2021 from https://www.congress.gov/event/117th-congress/house-event/114080/text

[2] Guidance Jointly Issued by the U.S. Departments of Transportation, Homeland Security, and Health and Human Services. (2020). The United States Framework for Airlines and Airports to Mitigate the Public Health Risks of Coronavirus. Runway to Recovery. https://www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/2022-02/Runway_to_Recovery_1.1_DEC2020_Final-508.pdf

[3] Transportation Security Administration. (n.d.). “Credential Authentication Technology.” https://www.tsa.gov/travel/security-screening/credential-authentication-technology

[4] Federal Aviation Administration (n. d.) Information for Airport Sponsors Considering COVID-19 Restrictions or Accommodations. https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/2021-08/UPDATED%20Information%20for%20Airport%20Sponsors%20Considering%20COVID-19%20Restrictions%20or%20Accommodations.pdf

[5] United Nations. (n.d.). Air travel down 60 per cent, as airline industry losses top $370 billion: ICAO | | UN News. United Nations. Retrieved September 16, 2022, from https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/01/1082302s

[6] Talbot, F. (2022). “The Impact of COVID-19 on Airports—and the Path to Recovery.” ACI World https://aci.aero/2022/10/06/the-impact-of-covid-19-on-airports-and-the-path-to-recovery/

[7] ACI Airport Health Accreditation | GBAC https://aci.aero/programs-and-services/airport-operations/aci-airport-health-accreditation-program/

[8] Wilhelmi, J. (2019). TRB Conference Proceedings 55: Airport Roles in Reducing Transmission of Communicable Diseases. Summary of a Workshop of the Airport Cooperative Research Program’s 2018 Insight Event. Transportation Research Board, Washington, DC. https://doi.org/10.17226/25367

[9] Global Biorisk Advisory Council. (2022).”GBAC Star Facility Accreditation.” Retrieved September 15, 2022, from https://gbac.issa.com/gbac-star-facility-accreditation/

[10] Department of Homeland Security. (2022). “Identifying Critical Infrastructure During COVID-19.” https://www.cisa.gov/topics/risk-management/coronavirus/identifying-critical-infrastructure-during-covid-19

[11] Artist, M. C. (2020). “Air Traffic Control Operational Contingency Plans.” Federal Aviation Administration. Retrieved September 14, 2022, from https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Order/JO_1900.47F_Final.pdf

Banner image credit: Unsplash