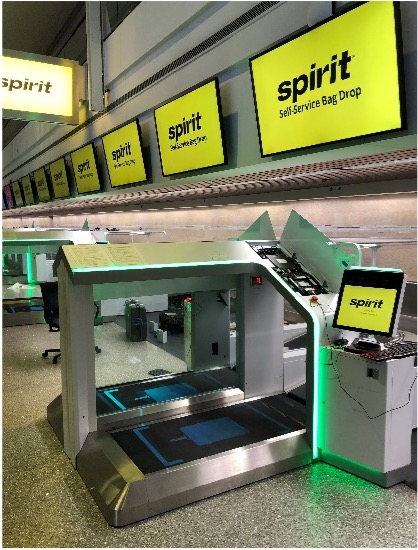

Self-service bag drops greatly aid passenger processing time and can be installed and operated in a common use fashion, extending self-service fully into the baggage handling process. The ability to self-tag has been in place for more than a decade now, with virtually all major airlines allowing their customers to attach the bag tag themselves. This was the first step of the self-service baggage journey, and itself brought many efficiencies in processing time to the experience, with a very streamlined drop process after tagging away from the drop location. Self-bag drop just takes this to the next level, cutting (by most all implementation reports) minutes from the processing time. It can also be configured to accommodate many airlines at a single location, usually managed by a ground handling representative of all of the users. In a common use environment, the airport may provide the baggage tag stock to the airlines. This is particularly true in a case where RFID has been widely deployed.

Example installation of self-service bag drop