Opening the Box: The Current State of Common Use at Airports

After years of lessons learned and through the progression of technology, several airport operators are starting to open The Box, as shown in Figure 1.4.1.

Figure 1.4.1: Opening the Box of Common Use

The following are examples of systems and processes that are being considered and implemented as common use:

- Signage, including all types and functionality, such as roadway, curbside, directional, and wayfinding, flight, baggage, gate, and ramp information display systems (FIDS, BIDS, GIDS, and RIDS)-with integration to other related systems, as appropriate.

- Curbside check-in/bag drop functionality, which could also include self-service elements.

- Voice over internet protocol phone system integration.

- Public address (PA) system for automated boarding announcements.

- Airport Operational Database (AODB)

-

- A central airport repository for data (typically only structured data like flight information, schedule times, or block times). The data contained in an AODB is used by numerous systems throughout an airport facility. The AODB's data storage can be onsite, in the cloud, and a hybrid of both.

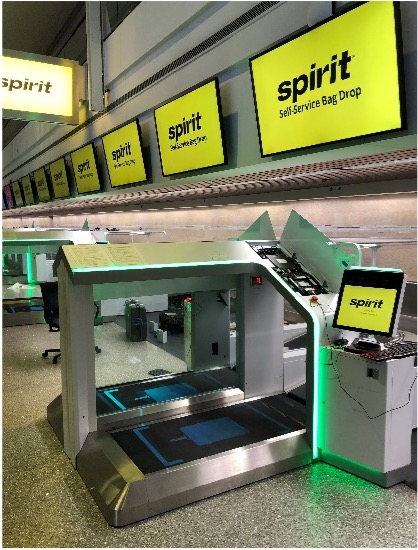

- Self-bag drop, an increasingly important capability in the airport environment.

- Outbound Baggage Processing

-

- This is an area that not many consider when thinking about common use. However, a baggage handling system (BHS) can either enhance or inhibit overall flexibility. Some BHS environments limit the routing from the input point to a make-up location for bags, while others allow for significant flexibility, routing bags accurately for a very long distance.

- Inbound Baggage Processing

-

- Like outbound BHS systems, inbound BHS systems are often overlooked in common use. In many cases today, airports large and small statically assign inbound carousels for airline use instead of dynamically assigning them based on real-time flight load. Dynamic assignment can lead to significant improvements in realized claim area capacity, enhanced customer service (with traffic spread over a wider number of carousels), and a reduction of baggage damage claims.

- Wired and Wireless Network Infrastructure

-

- Enables network connection throughout the facility and is vital for a broad variety of systems-across an equally broad range of stakeholders. Wireless connections were initially provided for use by passengers, usually in the form of Wi-Fi. Cellular connections (whether voice or data) were usually beamed from off-airport locations but were gradually moved to on-airport to mitigate the connectivity issues caused by the presence of concrete and steel and the distance between antennae and users. However, operational use also arrived, with agent-operated line-cutting tablets, baggage scanners, electronic flight bag (EFB) updates, and in-flight entertainment (IFE) downloads. New 5G infrastructure-often utilizing a private wireless network-is quickly becoming part of the airport communications environment. With a perpetual increase in interconnected devices coming to airports, maintaining, upgrading, and improving these communication networks will continue to be critical.

- Resource Management System (RMS)

-

- An airport resource management system provides the airport staff with tools to view and manage data from the AODB as well as from the RMS itself. More advanced RMSs allow for integration with common use system controls and for remote operation to address issues related to resource management.

- Ramp control, either in the form of staffed tower locations (increasingly operated by airports) or virtual ramp control systems, which allow for the same functionality to be provided from a remote site.

- Ramp systems, such as virtual docking guidance systems (VDGS), for marshaling aircraft to the gates in an automated manner. These units are most valuable when they are tightly integrated with other systems, consuming and providing data across the entire ecosystem. Even in less-integrated installations, these systems provide exact blocks-on and -off times, something that an airport operator typically does not have if they do not manage ramp control.

- Electrical recharge units on the ramp for an ever-widening array of electrified ground service equipment. The location and number of these units can either enhance or limit overall flexibility.

- Analytics systems throughout the environment, tied to a variety of sensors (cameras, LIDAR, Bluetooth, and even Wi-Fi).

- Biometrics-based systems, which are also used by other stakeholders, such as TSA and CBP.

- Systems aimed at irregular operations, such as airside kiosks in passenger areas and/or areas where various airlines (or multiple airlines) can assist passengers, with full access to all systems.

- Health measures equipment as appropriate to a particular situation, such as during a pandemic.

- Emergency storm detection and alerting systems, which are increasingly important for ramp worker safety.

Looking at and beyond this list, we can see the paramount need for stakeholder engagement. For example, when one airport operator was seeking to enable common use curbside bag tag printing and bag drop, they needed to engage with TSA because, up to that point, self-tagging was not allowed outside of the terminal space. Details of the plan and observation by all parties led to the realization that it was actually very secure and that it provided significant improvements to customer service by expanding the self-service environment.

Broadening this example, providing curbside assistance has been a challenge. This service is almost always provided by a contractor to the airline or airlines. Accordingly, the airlines usually do not open their full reservation systems to these contractors, preferring to have a slimmed-down application for them to use that minimizes access to just the functionality that the contractor needs. In the early days of system installation, this posed a challenge, as most carriers did not have an application usable on a common use platform. Over time, this situation has improved, but it can still be a challenge with new entrant airlines.

Even considering this list of advancements, the issue of integration is often not addressed. For example, an airport operator might have common use signage, but it is managed through a completely separate content management system. It can instead be integrated into the login for the workstation and/or associated with a scheduling program that utilizes real-time (or near real-time) inputs to alter signage in a timely, relevant manner.

Why Change is Needed

Throughout the industry, airport operators are finding many opportunities to leverage a common use approach beyond The Box described in this chapter. However, they are also running into barriers and experiencing pain points in their common use efforts-both inside and outside The Box. And the reality for most U.S. airports is that they do not have the holistic common use program needed to handle these opportunities and challenges.

A holistic common use program provides a strategic vision for common use, a roadmap for the future, and governance measures to keep any new opportunities in the proper alignment. It also provides a means for maintaining awareness of the ongoing challenges. So, when the decision-makers from up, down, across, and outside the organization have bought into and are involved in the program, working through these challenges becomes a much smoother process, and expanding to new opportunities is not only accepted-it is expected!

One airport leader put it this way: “You don't need to swallow the apple all at once. But you do need to know it's there.” A holistic common use program helps you do just that. For more on this, continue to Chapter 2.