The Range of Common Use Possibilities

To what can this operating philosophy of holistic common use be applied? Well…potentially everything.

The following provides a summary of what could be on the table at your airport-the specifics just depend on your needs. You will find that you are already providing many of these things commonly across stakeholder boundaries; they are already common use (and, in actuality, that began decades back with the runway that facilitated all arriving and departing traffic, without prejudice or discrimination towards any). The point that this WebResource will continually drive home is this: a holistic common use program considers everything, even things that are already (and perhaps obviously) being used commonly. The bottom line in this mode of thinking is flexibility across the entire ecosystem.

Figure 1.2.1: The Range of Common Use Possibilities

- Facilities and Related Services

- all buildings/physical space

- electricity

- amenities

- safety systems

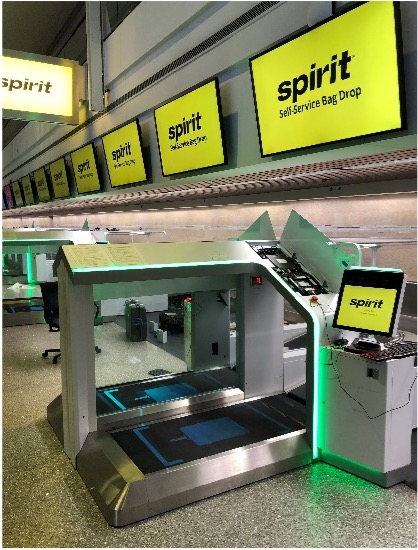

- baggage handling (bag drop and handling)

- concessions services (hours of operation, concession types, concession wayfinding)

- Airport Operations

- roadway operations, such as signage and curbside systems and services

- terminal operations, such as janitorial cleaning for systems such as kiosks and flight information display (FIDS) screens

- signage

- queue management

- airside operations, such as runways and taxiways

- Information Technology

- IT infrastructure, such as wired and wireless network and servers

- IT systems, such as passenger processing, gate management, communications, security/camera systems

- IT services, such as management support and maintenance

- IT security

- Airport Business Management

- contracts, such as the airline lease and use agreement

- governing municipal ordinances

- rates and charges that address per-turn charges and other flexible fees

- policies and procedures related to business aspects (e.g., reservation, reporting, and payment)

- a budgeting process that accounts for the various responsibilities related to attaining and maintaining a holistic common use implementation

Even in a Proprietary Terminal ...

When you look at this list, you are probably already ruling out that proprietary terminal that “has been and always will be” dedicated to (Fill-in-the-Blank) Airlines. But even in this case, a holistic common use program has a role to play; specifically, the program leaders need to drive the consideration that the predominant airline may be leaving gates (or other critical space) unused or may, over time, reduce their activity or even depart altogether. When the “thousand-pound gorilla” loses weight, a healthy common use program has already laid the groundwork for the airport to respond appropriately, allowing other growing airlines to fill the space.

Progressive airports in this category, dominated by a strong hub airline, often provide a common network on which services (even proprietary services) ride. The airport may also provide dynamic signage that can brightly display the brand images of the airlines and other stakeholders in the environment, while in prior generations, the primary branding opportunities were millwork and signage installations. They may also start providing systems that support common use in various parts of the facility. Some of these airport operators have even moved to a fully common use model with their terminal replacement/remodeling programs, shifting the new facilities over as they come online. The latest Newark terminal is an example of that approach. It will accommodate United Airlines (and others) in a full common use approach, from roadway to ramp. Subsequent terminal replacement at the airport will follow the same established template, leading to an airport that is entirely and holistically flexible.

Another example is signage. At one large U.S. airport that is a major hub for a particular airline, the traffic and routes for another airline are growing so that an entire half of one concourse is dedicated to that second growing airline. However, when the passenger of the non-dominant airline enters this airside terminal space at the main escalator entry point, the FIDS are proprietary to the dominant airline, providing no information relevant to their journey. One recent passenger of this route noted that he and his traveling companion even walked a significant distance into their general gate area to look for signage, only to find none in that portion of the terminal.

On the contrary, another U.S. airport that does have a holistic perspective has solved this issue by making their FIDS common use, even though they have a dominant airline that accounts for over 80% of their traffic.

Beyond the Gates

Whether in a proprietary or common terminal, consider the elements in the journey before or after the gates. Even in normal periods (e.g., not during a pandemic), airlines will always be riding a veritable roller coaster of events. And if the airport does not own, for example, the janitorial services in the publicly accessible areas, it is possible that the consistency of cleanliness will drop in locations that the airlines manage-both back and front of house. That is not meant to blame the airlines in any way; it is just the reality of cleaning a lesser-used space. On the other hand, the reality of cleaning and equipping a very heavily used space can also be challenging. A commonly deployed and well-trained custodial team can ebb and flow to accommodate the need across a wide environment and differing levels of terminal usage. (Click here for more on cleaning considerations.)

Another major consideration is the network. In most cases, an airline does not have technically qualified people on-site at all of their airports to manage things like security issues, service, and support. The airport operator can supply that expertise, but when issues occur with equipment that is not their own (back-office switches and/or servers or even such systems that are a part of the proprietary operation), they simply cannot assist with issues or outages. Through a common use approach, the airport operator can provide a data center that is central, consistent, secure, redundant, properly managed and conditioned, and properly powered.

Concession planning is another example of a process where a disconnect can occur. The airport can implement a consistent program after researching different business models and desires related to specific passenger demographics. Whether food and beverage or news and gift type concessions, consideration must be given to the type of passenger that will be in the area. Not only can the revenue penalty for a mismatch be severe, but it will result in a worse customer experience.