Chapter 1: Defining Common Use-A Broadening Term

What is Common Use and Why is it Beneficial?

An Operating Philosophy

Foundationally, common use is an operating philosophy that refers to the use of facilities, services, and infrastructure in a shared manner by multiple airport stakeholders (such as airlines, federal agencies, business partners, concessionaires, and any other entities doing business at the airport). What makes a common use approach so beneficial is the operational flexibility it enables.

Enhanced Flexibility = Improved Efficiency, Customer Service, and Sustainability

The flexibility enabled by a common use approach can greatly improve the efficiency of airport operations, perhaps most evidently when applied to terminal management. Put simply, when an area is statically leased or dedicated to an airline, space will go unused much more often than it would otherwise need to be. One airport operator thinking of terminal expansion said, ”Why build a new airside terminal facility when we could use what we have more efficiently?” This idea can be applied to the entire ecosystem beyond just terminal management.

The need for flexibility in operations was abundantly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, given the massive changes in passenger flows and flight adjustments.

A common use program can also benefit customer service by working with airline partners to spread flights across their facilities to ensure areas are not overbooked, leaving passengers sitting on the floor, unable to get food or recharge devices, and waiting for the restrooms. This leads to less money spent and the build-up of a very negative perception of the airport and the overall travel experience.

The Effects of Common Use

A common use approach has wide-ranging impacts, affecting all stakeholders-many in a very fundamental way. For example, a change in the check-in/bag drop hall (enabled by common use), which moves an airline to another location, also changes its curb drop-off location. This impacts signage, landside operations, and perhaps even roadway congestion, particularly during peak periods. In fact, such a move could also consist of a shift from one terminal to another, necessitating a change to roadway signage to ensure that both passengers and meeters and greeters find their way to the correct terminal, often via their transportation network company, taxi, or friend/relative drop-off.

A holistic approach to common use involves all impacted stakeholders-and these truly extend across the entire airport ecosystem to ensure each element of the operation and customer experience is considered and properly managed.

The Range of Common Use Possibilities

To what can this operating philosophy of holistic common use be applied? Well…potentially everything. Figure 1.1 provides a summary of what could be on the table at your airport-the specifics just depend on your needs.

Figure 1.1: The Range of Common Use Possibilities

Even in a Proprietary Terminal…

When you look at this list, you are probably already ruling out that proprietary terminal that ”has been and always will be” dedicated to (Fill-In-The-Blank) Airlines. But even in this case, a holistic common use program has a role to play; specifically, the program leaders need to drive the consideration that the predominant airline may be leaving gates (or other critical space) unused or may, over time, reduce their activity or even depart altogether.

Progressive airports in this category, dominated by a strong hub airline, often provide a common network on which services (even proprietary services) ride or dynamic signage to be used by all. Some of these airport operators have even moved to a fully common use model with their terminal replacement/remodeling programs, shifting the new facilities over as they come online. Newark is one such example.

Beyond the Gates

Whether in a proprietary or common terminal, consider the elements in the journey before or after the gates. Even in normal periods (e.g., not during a pandemic), airlines will always be riding a veritable roller coaster of events. And if the airport does not own, for example, the janitorial services in the publicly accessible areas, it is possible that the consistency of cleanliness will drop in locations that the airlines manage-both back and front of house. Another major consideration is the network. The airport can have trained staff ready to deal with airport-owned equipment in a way that may not be possible with equipment owned by other stakeholders. Another place where a disconnect can occur is concession planning. The airport can implement a consistent program after researching different business models and desires related to specific passenger demographics.

The Box: Background of Common Use at Airports

In the mid-1980s-early 2000s, several airports began using systems that enabled flexible use of check-in, gate, and ramp locations among various airlines. The term ”common use” got its start with the International Air Transport Association (IATA), which coined the phrase Common Use Terminal Equipment (CUTE) in establishing their Recommended Practice 1797. When an airport procured common use, this range of systems is what they implemented, typically including the following:

- Agent-facing systems with associated peripheral devices (boarding pass printers, bag tag printers, card swipes, boarding gate equipment, and bar code reading equipment.)

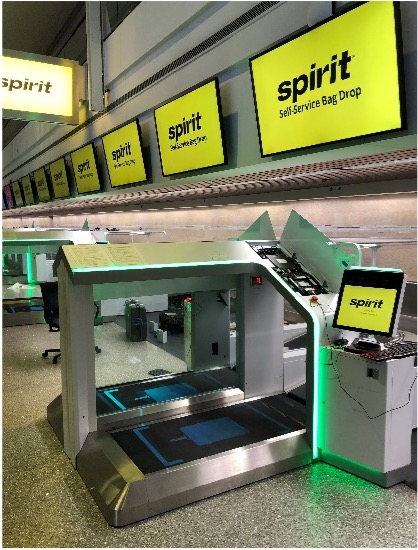

- Customer-facing systems, such as self-service kiosks, with the Common Use Self-Service standard confirmed by IATA and rolled out by airports and airlines in the early 2000s.

- Associated dynamic signage systems, which in the early days were not well-integrated and comprised rather tedious manual systems and monitors that may or may not have displayed the precise color used by the air airline logos.

This is ”The Box” of common use, as summarized in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: The Box of Common Use

Leaders in the Industry

The following agencies have helped guide the aviation industry to best practices and have impacted the deployment and adoption of common use systems:

- International Air Transport Association (IATA)

- Airports Council International (ACI)

- Airlines for America (A4A)

- American Association of Airport Executives (AAAE)

Although some of these organizations are starting to expand, for the most part, their efforts have been focused on The Box.

Opening The Box: The Current State of Common Use at Airports

After years of lessons learned and through the progression of technology, several airport operators are starting to open The Box, as shown in Figure 1.3.

Figure 1.3: Opening the Box of Common Use

This open box includes systems and processes that directly support airport, airline, and passenger needs, such as signage, including all types and functionality; curbside check-in and self-bag drop functionality; voice over internet protocol phone system integration; outbound and inbound baggage processing; wired and wireless network infrastructure; ramp systems and control; electrical recharge units; analytics systems; biometrics-based systems; airport operational databases; resource management systems; and many others spanning all facilities, services, and stakeholders in the airport environment.

Why Change is Needed

Throughout the industry, airport operators are finding many opportunities to leverage a common use approach beyond The Box described in this chapter. However, they are also running into barriers and experiencing pain points in their common use efforts-both inside and outside The Box. And the reality for most U.S. airports is that they do not have the holistic common use program needed to handle these opportunities and challenges.

One airport leader put it this way: ”You don't need to swallow the apple all at once. But you do need to know it's there.” A holistic common use program helps you do just that, and for more on this, keep reading into Chapter 2.