Issues and Challenges by Stakeholder Group

In the early years of common use, there were several challenges with common use solutions not enabling airlines to provide the same level of quality experience for their passengers as they did in their proprietary environments. Over the past decade, common use solutions have matured as solution providers have sought to address many of these concerns, but some do still exist. Moving forward, as more stakeholders get involved and more systems are being integrated, there are new challenges that need to be addressed.

The following provides a summary of the ongoing issues and challenges with common use at airports, gathered from interviews and case studies with over 25 entities in the aviation industry. Be aware of these as you plan for common use at your airport.

Airports

Inconsistent Experience and Capability

Inconsistency issues, internal to the airport and from one airline to another, are significant for airports in common use environments. The holistic common use program promotes a level of integration between airport systems and airline systems. This integration requires consistency between the airline and airport system applications; therefore, airports are often unable to update their applications until the airlines have adopted the new common use systems.

Other inconsistency issues include the following:

- Some airlines plan to keep some systems proprietary, complicating the transition to full common use.

- Data sharing is increasingly complicated by the growing number of stakeholders involved. With solution providers, airlines, and airport operators all having some level of access to user data, new data standards and policies will need to be formalized and adopted.

- Many airport operators employ a mixture of common use and proprietary use. This can result in the segmentation of older and more advanced technology capabilities in the network.

- Airports often have systems using outdated hardware and software, causing problems in implementation, design, cybersecurity, and other capabilities. It can also impede or prevent an airport operator's ability to take advantage of solution provider updates and new features. Additionally, many airports have outdated technology that increases the cost and time needed to transition to common use solutions. This is a significant frustration with major airlines that aggressively seek to incorporate new technology to increase customer experience and improve operational efficiencies.

Support and Buy-in

Support issues naturally follow the technical challenges noted above. Solution provider and staff skills, service-level agreements, solution provider technician turnover, and differing operational responsibilities to support mixed common use and proprietary environments all play a part in these challenges. There are also support issues relating to payment card industry data security standards and other data security considerations. Buy-in is also a challenge, with many airlines not yet on board with common use.

Airlines

Inconsistency Between Airports

Airlines have found that implementing and managing common use systems throughout their airport stations is most challenging because of how inconsistent their experience is across airports. Some airports do not even have a common use program. Where there is a program, a given airport's maturity, technology infrastructure, and technology capabilities may be somewhat unique. There is also inconsistency in the level of training that airline/airport staff receive on the common use systems.

Quality of Support

Considerable issues also arise from the quality of support provided by the airport operator and any common use solution providers. Support issues generally include timeliness of support, level of involvement, delays in operations, and poorly defined and executed roles and responsibilities. At a first review of the noted issues, it would seem they are primarily related to the solution provider. However, the airport operator is ultimately accountable for designing, setting up, and managing the common use program; therefore, they have a significant role and power to address these issues.

Other issues facing airlines include the following:

- Challenges arise in establishing new relationships and coordination with common use solution providers (installation, upgrades, ongoing support, etc.), and some airports have struggled to establish effective working relationships and a solid knowledge base.

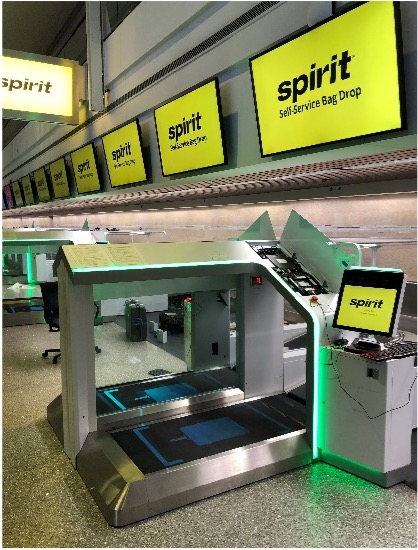

- Initial investment when transitioning to common use can be a barrier or cause a partial common use solution to be pursued instead of a holistic program. In most cases, even with a simple installation, a wholesale change of the millwork is necessary, both in the bag drop locations and at the gates. The complexity and cost of these changes can initially appear somewhat daunting, but the benefits generally far outweigh these costs.

- Constraints on branding compared to the freedom of proprietary gates and counters are still an issue for some airlines as it relates to millwork, but it has been greatly mitigated using dynamic signage, which has become bigger, brighter, and less expensive, with many additional immersive dynamic capabilities.

Regulatory Agencies

The research team consulted the TSA, FAA, and CBP to gain a better understanding of their unique issues/challenges in implementing common use systems. The issues identified by regulatory agencies are more complex than those identified by airlines, airports, and passengers, and they span a broader set of stakeholders.

These are relatively new issues, addressing recent and anticipated innovations in biometrics and identification systems such as health passports. Other challenges include governance (including roles and responsibilities), data sharing (means, methods, and security) between all parties, credentialing tokens, technology, passenger and airport buy-in, funding, and collaboration between all involved parties. For many of these issues, the agencies are actively working with small pilot programs to reduce complexity and speed up progress.

The primary responsibility and goal of these regulatory agencies are to keep passengers and workers safe. Alongside the goal of safety are several other ancillary goals.

Data Sharing

Data sharing becomes an obstacle to the growth of common use when different groups are unwilling to participate in new programs or solutions. For example, to have health data available for airport and airline staff on-site when processing passengers, the passengers need to consent to provide such information. Such information sharing becomes more difficult as more stakeholders are introduced that need access to the data. The FAA mentioned that data flows among airports, airlines, and the FAA can cause issues and can be improved by better data sharing. This is an essential part of collaborative decision-making (CDM), which is in the trial phase at several airports and will roll out nationally at some point in the future.

Funding

Funding also comes into play for many agencies, as their funding is tied to yearly governmental budgets. Delays in the rollout of certain new systems can then be caused by any holdup in new funding bills. Funding also comes into play with regard to federal assistance and eligibility for such programs as Passenger Facility Charges (PFCs), which by definition must expand airport capacity.

Innovation

New developments in biometrics, health credentials, and other technologies are showing the need for better innovation planning for regulatory agencies. These agencies will often need an airport/airline partner in order to test new technology or processes.

Market Access

Many years ago, the U.S. Department of Transportation realized that some airlines were inordinately tying up the available space at certain airports as an anti-competitive measure. It would not have been an issue had they used all of the facilities that were statically leased, but instead, many of those areas stood entirely unused, and the airlines were unwilling to release them from leasehold, which would have allowed competition to grow.

Accordingly, the FAA now requires airports to file competition plans if fifty percent or more of their enplanements per year are handled by one or two airlines. The competition plan indicates how new entrants or growth in routes and flights by extant airlines would be accommodated. This can be challenging in a scenario with proprietary leased space; however, airports preparing these plans may find immediate benefit in demonstrating existing and planned implementation of common use facilities that safeguard access to new entrants within the market. Common use gates, passenger boarding bridges, and ticket counters can serve to eliminate barriers to entry in the establishment of new air service by non-incumbent airlines at capacity-constrained or hub-dominated airports.

For example, at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, the FAA noted specifically that the strategic implementation of common use for ticket counters, gates, and passenger boarding bridges was critical in demonstrating the airport's commitment to a competitive environment.

Business Partners

Common Use Solution Provider

Data sharing is a big concern for some common use solution providers. In particular, they are concerned that data provided by the solution provider could then be turned over and used by a competing provider.

Providers also wish to be viewed as service providers and not just solution providers for a product. The business models of most common use providers will reflect this fact. Support will be needed on an ongoing basis in order for the common use systems to function as intended.

Common use providers also want to enable an end-to-end experience for passenger processing. Solutions are designed to touch major checkpoints throughout the passenger journey.

Ground Handler

The research team also met with a baggage and cargo handling company for their perspective on the common use environment. One key issue identified was that the baggage/cargo industry is antiquated in how it operates. One example is the need for a provider to bring their full set of equipment to a gate, even if it is only for one flight. A common use solution for baggage handling equipment could eliminate this need for constantly shuffling different providers' equipment. Airports would need to become the provider of a common equipment pool and manage all of the added complexities-contracts, solution providers, billing, etc. One issue identified by Swissport with using a full set of common use equipment at each gate was that when equipment goes missing, chaos can ensue. Airport operators would need to have rules and agreements for what happens if an airline crew misuses or damages common use equipment.

Other issues include the following:

- A desire to have video analytics to assist in incident investigations on the ramp.

- A preference for auto-docking systems because they help reduce risks.

- There is a lack of space for baggage induction.

- There is a need for alerts if a jet bridge is not aligned properly.

- There is a desire to be consulted during airport design.

- There are concerns about handling offsite or animal cargo.

- They would like to have more automation.

- They want roles laid out by the airport for who does what.

- Overall network connectivity on the ramp.

Cybersecurity Services

The research team consulted a cybersecurity expert on the IT considerations and issues with common use deployments. Due to these new common use systems being designed for integration with outside systems and databases, there is an increased risk of security breaches. More and more passenger data is collected as a result of new common use systems, and all parties involved need to be sure everything is being done to protect this data.

Architect / Engineer

An interview with Frankfurt Airport staff brought out the need for well-designed terminal architecture. There is a need for space and flow to be priorities when an airport is constructing new facilities. This airport mentioned that space management is vital when implementing new solutions that affect passenger flows.

Engineers, both internal and contracted, will need to have input in the design of terminals, especially when considering the implementation of new common use systems. Many deployments of common use will require new infrastructures such as network equipment or power supplies. Harry Reid International Airport management specifically mentioned the need for airports to have industrial automation engineers on staff. Having engineering involved with a holistic common use program will help to prevent any issues delivering on planned new solutions and services.

Passengers

The transition to common use solutions can greatly benefit the passenger experience. However, along with these benefits come difficulties falling into two primary categories.

The common issue across the three primary stakeholders' groups (airlines, airports, and passengers) is support. For passengers, technical support issues generally relate to airport apps-specifically whether they are frequently updated, accommodate the needs of those with disabilities, and have a purpose that is clearly distinguished from the purposes of airline apps. Passengers find non-technical support issues pertaining to support personnel, specifically indicating a need for support personnel to guide them to the correct kiosks or information. Passengers with disabilities and those with small children both asked for more support personnel assistance to be available.

The other significant category of issues is passenger communication. For example, passengers of all demographics-especially those with disabilities-stated they need easier-to-understand signage as they find their way from the roadways to their gate. They also need education prior to airport arrival on whether there is an airport app and what information it provides, as well as what services the airport offers. Airport operators need to improve systems such as digital signage, wayfinding, and disability support technology to inform passengers of the availability, function, and operation of new systems.

Of course, much of passenger communication is moving to mobile. In that sense, the airport may be limited to direct mobile communication via an app. The fact is that the airlines have the most direct communication channel with the passengers, usually having an email address and often a phone number for SMS messages. They know where the passengers are expected to be, when they are to be there, and where they are traveling to, but probably do not have an indication of whether the passengers will show up to fly.