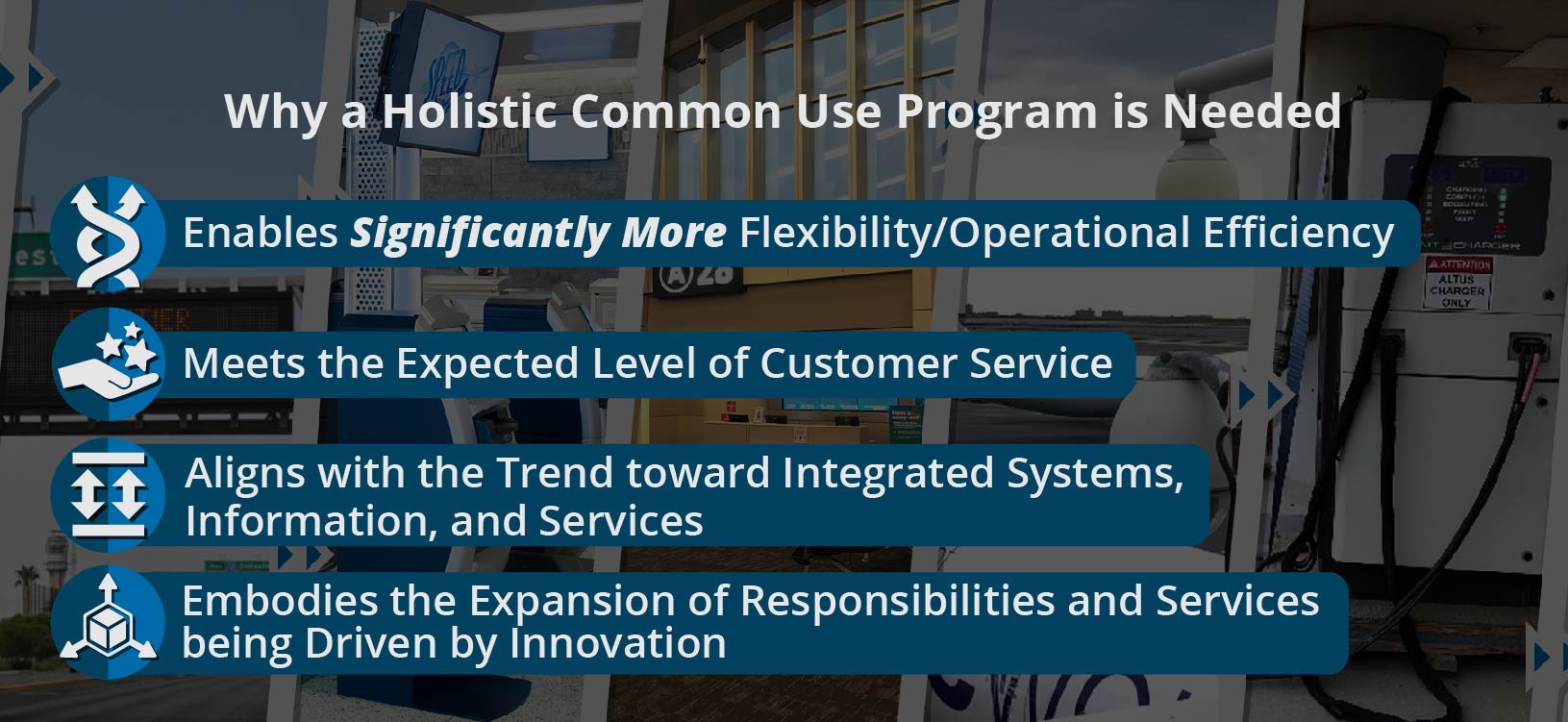

Why a Holistic Common Use Program is Needed

The Box of common use (described in Chapter 1) is already in place at several airports-or at least in specific terminals-and there is no question as to its benefits, even under a rather limited implementation. Yet most of these programs have yet to embody a truly holistic perspective. But is this really that important, and if so, why?

The following reasons shown in Figure 2.2.1 make a holistic common use program a necessity for those who wish to operate their airport efficiently and serve their airline partners, stakeholders, and customers effectively.

Figure 2.2.1 Why a Holistic Common Use Program is Needed

Enables Significantly More Flexibility/Operational Efficiency

A holistic view of common use enables more flexibility and operational efficiency across all airport functions simply because the entire environment is being addressed instead of just one piece of it. This wide view helps to mitigate elements popping up as challenging surprises when they are least needed. For example, core systems in The Box of common use allow airlines to be moved from one gate to another. Basic. But what about the camera systems? If these are still proprietary, and the move is happening now, the move will be delayed-or at least the functionality provided by a proprietary camera system, perhaps on the ramp, will not be available for a long period of time. This can adversely impact safety, security, and overall operational situational awareness. Moving these types of systems can take months.

This brings to light other issues, such as ramp information display systems that are proprietary and need to be considered in the move. Another issue may be wireless connectivity on the ramp for things like baggage scanning and other operational uses. If that is proprietary, the move cannot happen-or, if it does proceed, limited functionality in the new area will be a new reality.

One smaller airport interviewed for this project has The Box of common use. However, only one of their gates has a radio frequency identification (RFID)-enabled printer, and one of their airlines relies on it. This means that on the days when it would be highly beneficial to move that airline's flights to another gate, the move cannot happen, or if it does, that airline will operate less efficiently at the new gate. Sometimes, that gate sits empty for extended periods, but since the airline needs to use it later, the airport operator must hold it out of the mix, sometimes causing longer hold times for flights on the ramp. (One solution here might be to implement RFID printers throughout the gate area at a relatively limited additional cost per printer.)

Another example that is popping up for many airports is charging stations for electric ground service equipment (eGSE) vehicles. The eGSE trend is growing exponentially, and at many airports, there is only one set of recharge units for ramp vehicles at one gate for a given airline-and it uses that airline's proprietary and unique equipment. A further complicating factor is that even when there is a desire to place charging stations at other gates, there is not enough power to accommodate the additional stations. In this instance, the airport operator may be tempted to let the airline handle the infrastructure expansion, but this can severely undermine what was once a flexible, common use approach.

A holistic view considers all operational elements at a time when something can be done about them.

Meets the Expected Level of Customer Experience

With the advancement of technology and the growth of customer service tools, the modern customer has become accustomed to a seamless and high-quality experience. A holistic approach to common use that considers all details within a given piece of the passenger journey leads to enhanced customer service.

A great example of this is signage. Airport operators with The Box of common use are able to move the check-in, bag drop, or gate locations of a given airline or flight. But an operator with a holistic perspective will take this a step further, considering where the affected passengers may be when they need information about these changes communicated to them through signage. This is necessary in any space, whether proprietary or common use. For instance, consider the passenger who deplanes a flight with one airline but has a connecting flight with a partner airline. This passenger needs information from both airlines and may need wayfinding assistance.

More complicated scenarios can arise, however, particularly for the many passengers who use online travel websites to find the cheapest itinerary, which sometimes entails the passenger changing airlines-sometimes not to an alliance or partner airline-in the middle of their journey. The challenge that arises is that these websites usually pay no attention to the gate locations across the journey, which means the passenger could walk off their first flight only to see no signage providing up-to-date information on their next flight. One airport operator learned of this happening at his airport when a customer missed her connecting flight after landing in one terminal without any idea of where to find her next flight. After reading the resulting complaint and wanting to assist, he took the initiative to reach out and offer to meet up with her to personally make that same walking transition on her next visit. During this walkthrough, the airport operator's eyes were opened to the many places where signage would have been immensely helpful to this customer's journey. This was important because he noted there were several other passengers who had been booked on the exact same computerized itinerary, which called for a non-alliance connection between airlines in far-flung terminals, requiring significant navigation and a shuttle ride.

Another example is wireless connectivity to enhance the operation both outside and inside the terminal area-the latter being directly applicable to enhancing customer service. Whether outside on the ramp, where efficient operations increasingly rely on connectivity (such as baggage reconciliation, electronic flight bags, ruggedized maintenance tablets, or even data downloads from the plane and its engines), difficulties in any of these areas can adversely impact the ability to stay on schedule. Inside the terminal, the ability of the agents to “line bust” or reaccommodate passengers affected by an irregular operations situation is greatly aided by a solid network connection-almost always wireless-as the agent takes the system to the passengers. These functions are certainly outside of The Box, yet they also facilitate systems and services that directly affect the customer. A late launch on a flight can have challenging ramifications at the originating airport, but it can also cause delays that ripple downline throughout the day. The in-terminal services afforded by agent-operated mobile devices have a more direct effect on customer service, but at the end of the day, the robust nature of that connectivity is very important. Yet, when provided on a proprietary basis, overall flexibility and customer experience is certainly diminished.

A holistic view considers all terminals and transition possibilities, improving the customer's journey in every way possible by providing systems, services, and signage in a consistent, considered fashion-something individual airlines or other stakeholders may not be able to accomplish singularly.

Consider: What if individual stakeholders maintained the public restrooms near their respective areas of operation? There would be no singular standard, and some would be far better than others. Perhaps more to the point, some would almost certainly not meet the desired cleanliness standard, and this has been shown to be a significant item on the customer experience index. Considering this and other examples, the airport is the only entity that can pay close attention to all customers, ensuring their journey is consistently top-notch!

Aligns with the Trend toward Integrated Systems, Information, and Services

A holistic model of airport common use is vital due to the increase in systems and processing being added to common use programs and environments. From check-in kiosks to e-gates to CCTV cameras, airport operators have more systems than ever to consider moving to the common use environment. With this proliferation of systems, the integration of data into a centralized (or mostly centralized) location is a major trend that is here to stay, creating opportunities to provide new customer services, generate new revenue opportunities, and increase flexibility and efficiency.

One example is an enhancement of flight information display systems to provide passengers with an estimated travel time from entering the airport to arriving at their gate. This is only possible through the integration of several data sources, such as the length of queue lines in check-in/bag drop areas, wait times for the security checkpoint, and the number of checkpoints open at that time.

Another example is analyzing how many passengers are arriving at the curb or are in a check-in hall to provide the TSA with an estimate of how many passengers are coming to them at a particular time-and to exactly which checkpoint, in the case of a larger airport. The data could come from queue management tools counting the number of passengers in the check-in area. It could simply come from the number of passengers being processed by a particular airline. It could come earlier by identifying when buses full of passengers enter the airport. One airport tested a LIDAR-based technology to differentiate cars from people to measure the number of vehicles in a particular area. Whichever way the data is collected, some modicum of advance notice could give TSA enough time to optimize their staffing for particular checkpoint areas, whereas having to be reactive could mean that they lose the battle very early and struggle to catch up and/or keep up again-often over a period of several hours.

Services like these can only be provided by an airport operator that takes responsibility to gather and share operational data to better manage their operation, serve their customers, and enable their partners to do the same.

Embodies the Expansion of Responsibilities and Services Being Driven by Innovation

Over the last 5 to 10 years, the entrance of several new processes and technologies has disrupted the traditional split of responsibilities between the airport operator and its stakeholders. When innovation occurs, who takes the lead? The operator who truly wants their airport to best serve their customers and partners will always seek to coordinate the introduction of innovation, and a holistic common use perspective perfectly embodies this.

A very recent example is that of virtual queueing. Although this technology has been used for several years in waiting rooms and theme park lines, it was not widely considered by airport operators until the COVID-19 pandemic. At the onset of the pandemic, the concern was that if airports were to maintain the six-foot physical distancing requirement when passengers returned, lines would literally be out the door, up the curb, and onto the roadways. The aviation industry quickly responded with the development of minimum airport specifications, outreach to various virtual queuing solution providers, and the establishment of airport trials at BOS, DEN, and SEA. The first few airport trials of this technology for the security checkpoint lines were widely successful, and they have highlighted just how important it is that the airport operators be the driver and provider of the service. Click this pop-up link for more about virtual queuing.

Another innovation driving the increased responsibility of airport operators is the increased use of technology in the airfield environment. What was once the last bastion of “operation from clipboards” is now increasingly relying on wireless connectivity for tools such as automated docking systems, autonomous airside vehicles, robotics, camera analytics, and dynamic signage (such as for ramp information or countdown clocks).

One more example is that of biometrics in support of a more seamless passenger journey. Pilots and implementations to date have shown great benefit in identity verification at bag drop, security checkpoints, lounge entry, and boarding. There are also strong use cases in the concessions space. But when this is done in a proprietary manner (for instance, with just one airline) or if the airport operator is not the true coordinator, the program will be designed in a way that only works for a subset of passengers. And though other stakeholders may be interested in joining, the standards are not in place for a clear entry. There is also a strong possibility that a myriad of different programs will spring up, and the passenger will generally have to enroll in several of them to achieve any real benefit.

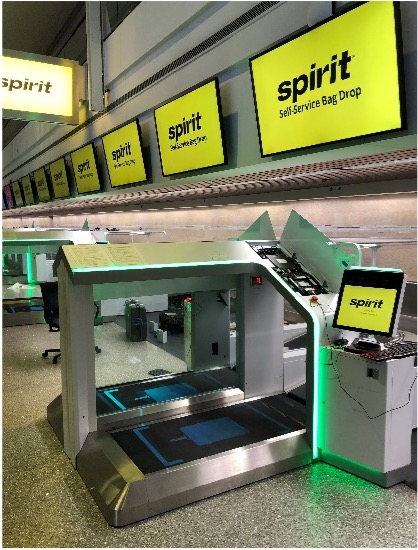

An airport operator with a holistic perspective keeps a finger on the pulse of industry and innovation to understand what is coming. In most cases, not all stakeholders will seek to implement every advancement right away. But that does not mean the common use airport operator needs to hold the innovators back. For example, recently, an airport operator had only one of their major airlines asking them to install self-bag drop units. The operator worked with that airline to put in a few units as a way to test this new process and set common standards and equipment in place for any other airline that also wanted in on the program. Reward earlier adopters and take the initiative to put in place a plan for a common use future.

Though all of this may seem intimidating, understand that this is why a program and long-term vision is needed. An oft-quoted old proverb puts it this way: “The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second-best time is now.”