What is Common Use and Why is it Beneficial?

An Operating Philosophy

Foundationally, common use is an operating philosophy that refers to the use of facilities, services, and infrastructure in a shared manner by multiple airport stakeholders (such as airlines, federal agencies, business partners, concessionaires, and any other entities doing business at the airport).

What makes a common use approach so beneficial is the operational flexibility it enables. One industry leader put it simply: “The three main reasons for common use are (1) flexibility, (2) flexibility, and (3) flexibility.”

A classic example of a common use approach is the operation of the runway. It is used by any airline, flight (regardless of origin or destination), and aircraft of any given size. Another is the set of roadways leading up to the airport. At most airports, the passenger approaches using the same roads and viewing the same signage (static or dynamic) as those traveling with a different airline.

In this light, much of what happens at almost any airport is, in practice, common use. Though airports were largely common use for a long while, over the years, operators began working with airlines to provide dedicated terminals, concourses, or gates in which to conduct their operations and serve their customers. Though these arrangements can be a great option (and, in some cases, the most ideal), there is no question that the overall efficiency of the airport's space is diminished.

Enhanced Flexibility = Improved Efficiency, Customer Service, and Sustainability

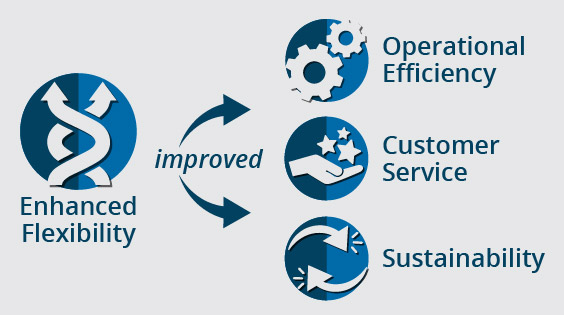

The flexibility enabled by a common use approach can improve overall efficiency, customer service, and sustainability, as shown in Figure 1.1.1.

Figure 1.1.1: Enhanced Flexibility = Improved Efficiency, Customer Service, and Sustainability

Operational Efficiency

Common use can greatly improve the efficiency of airport operations, perhaps most evidently when applied to terminal management. Put simply, when an area is statically leased or dedicated to an airline, space will go unused much more often than it would otherwise need to be.

This puts an artificial cap on throughput, even though the demand for growth may exist, and it means fewer passengers will frequent concessions, rent cars, stay in hotels, eat at local restaurants, or visit local attractions-everything essential to a thriving local community. These limitations can have a significant adverse effect on the overall economic impact (both direct and indirect) that the local airport stimulates.

Many airports continue in this dedicated model, and when growth continues, those that have space build additional facilities to be used in the same inefficient manner. The obvious problem for most is that new facilities take up space (which most do not have) and cost money (something all airports do not have enough of).

One airport operator was considering building an additional terminal to accommodate growth, and as they were having one particular meeting, the team looked out over most of the terminal environment, noting that every gate in sight was empty. This sparked the question, “Why build a new airside terminal facility when we could use what we have more efficiently?”

Customer Service and Air Service Development

A more efficiently managed airport can provide more destinations and flight times (through its airline partners) to its community-all in a manner that the facility can actually handle. The reality for many airports is that the airline's route planners can leave customers' actual, on-the-ground experience out of the equation. Meaning if the demand for a new route exists, it is added, regardless of whether the airport can truly handle it. It is then up to the airline's station manager to figure it out. Many times, this means facilities are overbooked during peak periods, and passengers are left sitting on the floor, unable to get food or recharge devices, and waiting for the restrooms-all the while spending less money and building up a very negative perception of the airport and the overall travel experience.

In this scenario, a common use program would have allowed flights to be spread across their facilities in a manner that optimized both operational efficiency and drastically improved the customer experience.

The need for flexibility in operations was abundantly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic, given the massive changes in passenger flows and flight adjustments. Many airports were forced to collapse operations into a very specific defined location, in some cases with proximity to the only open security checkpoint and/or open concessions as other stakeholders also quickly consolidated operations. Airports with common use installations had the inherent flexibility that allowed them to make these adjustments very quickly and relatively seamlessly. Those that had extensive proprietary space and associated systems throughout the environment had a much more challenging time adjusting to the necessary changes.

Common use allows all facility usage to be flexible, facilitating an almost infinite matrix of usage options that can be tailored to meet usage demands at any time. Not all airlines operate on the same general or specific schedules, though there will inevitably be peak days and/or times at any airport. There may be airlines-particularly in the ultra-low-cost segment-that are highly dependent on night or other off-peak flights, while other airlines operate a more traditional daytime schedule. Other variables may also result in peak activity times, for example, international departures to particular destinations. From an airline standpoint, the ability to pay for what they use (rather than for statically leased space that they may not be using) can drastically lower what they pay. A holistic common use implementation provides a cost-effective, customer-friendly, and operationally efficient environment that can be a real catalyst for growth-both at the airport and even in the community.

In a case study for this project, the director of Fresno Yosemite International Airport noted that common use had been an incredible game-changer for their small airport, allowing them the flexibility to grow into significant mainline service, adding new routes and airlines and experiencing significant growth in international service as well. “We would never have been able to expand the terminal facilities to accommodate the growth needed for a proprietary operation. The flexibility brought by common use was a key enabler for our growth, which plays a vital economic and air service role in Fresno and surrounding communities.”

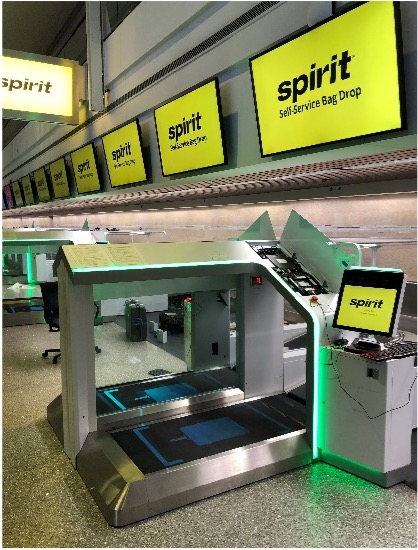

Systems can be implemented consistently across the environment to accommodate airline and passenger needs. Self-service, available now across virtually all of the journey experience, can be deployed in a fashion that meets the needs of all and even pushes the envelope in terms of new technology and processes. Bold and bright dynamic signage can guide the customer seamlessly to the proper locations while also placing the airline's brand image distinctly on display. From the roadway to the ramp, systems can be implemented in a common use manner, following the latest standards and providing efficient passenger and bag processing. Click the following pop-up links for more details on these topics: self-service bag drops and irregular operations.

Sustainability

Statically assigned airport space often goes unused while unnecessarily consuming power. An airport operator with a common use approach can use space more efficiently and, therefore, plan power consumption more intelligently. Additionally, increased operational efficiency can reduce the time aircraft need to hot-hold off the gate, leading to less fuel consumption. One case study airport, Harry Reid (formerly McCarran) International Airport, adjusted the business arrangements around gate use fees such that an airline could unload at any available gate without charge, with a tow over to its normally assigned preferential gate for departure. This adjustment directly benefitted the customer experience and sustainability, as passengers arriving early, who otherwise would have had to hold off-gate, were allowed to swiftly depart the aircraft and get directly to their business or fun in Las Vegas.

Enabling Collaboration

None of this should be taken to mean the airport has to act like a traffic officer. A good program empowers airlines to work with each other to swap the use of preferentially assigned gates as needed to benefit both their operational efficiency and the customers themselves better. This may or may not happen organically, but the fact that it is facilitated by both the contract and the technology certainly serves to catalyze such real-time flexibility. The biggest difference is that the airport operator has taken responsibility to help ensure the customer is best served while traveling through their facility and into or out from their community or onward to another destination. In short, with a holistic common use perspective, the airport has taken the reigns to drive operational and space use efficiencies while also moving the needle positively regarding the customer experience. Rather than being along for the ride, the airport can actively bring all of the many stakeholders and respective systems into alignment to the great benefit of all!

The Effects of Common Use

A common use approach has wide-ranging impacts, affecting all stakeholders-many in a very fundamental way. For example, a change in the check-in/bag drop hall (enabled by common use), which moves an airline to another location, also changes their curb drop-off location. This impacts signage, landside operations, and perhaps even roadway congestion, particularly during peak periods. In fact, such a move could also consist of a shift from one terminal to another, necessitating a change to roadway signage to ensure that both passengers and meeters and greeters find their way to the correct terminal, often via their transportation network company (TNC), taxi, or friend/relative drop-off. Further, airport maps on websites, apps, and wayfinding stations in the terminal will need to be updated, as must all relevant signage. Wheelchair staging locations and signage may need to be adjusted, and camera views and security clearance to access points may also need to be adjusted. Of course, kiosks and self-bag drop machines will likely need to be reassigned to a new airline if operated in “dedicated” mode (an industry-standard method of assigning a common use device, such as a common use self-service kiosk, to automatically display the front screen for a given airline in a particular location).

At the security checkpoint, the aforementioned change may be cause for adjustment by the TSA, as the affected airline's passengers might flow through a different checkpoint, either in the same or in another terminal. These moves must be well-coordinated with all stakeholders across the ecosystem.

Another consideration point is that of airport concessions. Certain concessions pair better with certain airlines and routes. For instance, higher-end restaurants and shops pair better with higher-priced fares, and international routes pair well with duty-free shops. Any change in gate assignment must consider these dynamics since they can affect the business of the concessions and, ultimately, the customer experience. Concession hours must also be considered, as the shift of an airline can impact the flight schedule in a particular area, reducing passengers in one place while increasing them in another location. It could necessitate an adjustment to operating hours.

The shift from one gate (or terminal area) to another also has far-reaching effects. In that area, systems both inside the terminal environment and outside on the ramp could be affected. Dynamic signage (and all associated systems/signs leading passengers to that area) should be correctly deployed. All of the systems at the gate need to support the moving airline and the intricacies of the operation, such as the Customs and Border Patrol's Traveler Verification Service (TVS) deployed for international departures and/or biometric boarding. On the ramp, automated docking systems, camera systems, signage, and other ramp information display systems (RIDS) will need to properly reflect the shifted operation.

A holistic approach to common use involves all impacted stakeholders-and these truly extend across the entire airport ecosystem to ensure each element of the operation and customer experience is considered and properly managed.